Character and Costume Design by Aaron Diaz

Character design is paramount to pretty much any kind of animation & comic. Most animated series or films & comics have things in them, and some of those things are characters, and those characters better be well-designed. Design allows the artist to communicate essential information to the reader about a character, and a good design allows for versatility independent of minor details. I'll probably write a more specific post later about the mechanics of character design, but for now I'm just compiling a list of my personal favorite comic character designs. All of the one I list exhibit all of the key essential design elements:

Here are my favorite designs from the world of comics:

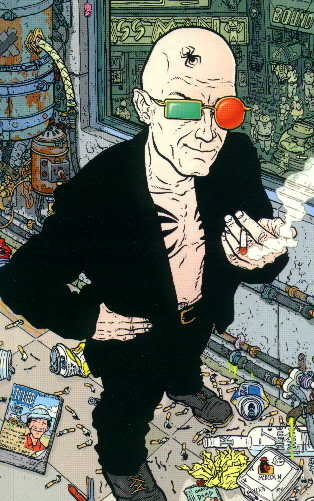

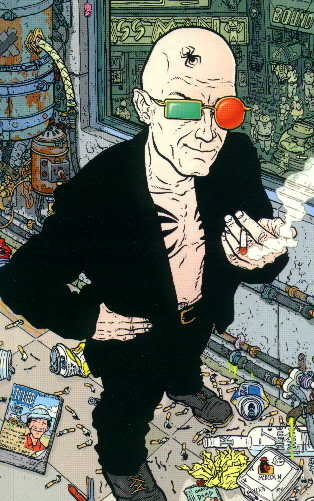

The crotchety protagonist from Warren Ellis' spectacular cyberpunk series Transmetropolitan was designed by Darick Robertson. It's a masterful exercise in simplicity; Spider's outfit is mostly black, bisected by a "band" of light tone created by his exposed torso. He's a bit of a looming figure, but it's broken up nicely by the odd glasses, which are really the most distinct element of the character. They're not only instantly recognizable, but the unusual pairing of shapes suggests a facial expression (specifically the raising of an eyebrow). This is a great twist on the iconic nature of sunglasses, which are traditionally associated with the hiding of expression.

You can pretty much know it's him from any angle, and even from silhouette, Robertson generally maintains the sunglasses as visible. Clarity of design and the striking shapes makes Spider Jerusalem a visually memorable character.

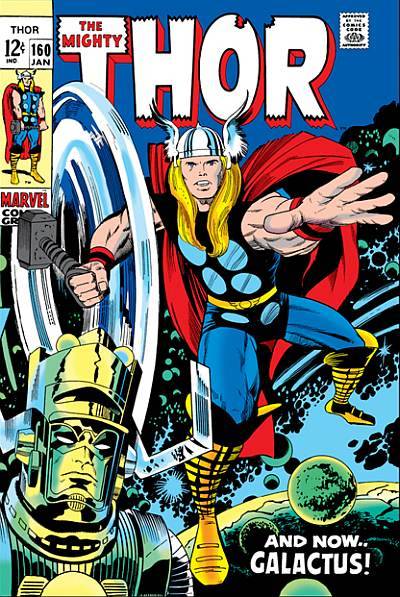

Designed by the king of superhero comics, Jack Kirby, Thor succeeds in suggesting historical and mythological elements without being bound to them stylistically. Aside from the hammer, there's very little that's literally Norse about the details of Thor's outfit, but Kirby gets the point across effectively and stylishly. Wrapped boots, the suggested armor circles and the feathered helmet are there to add to the theme of a near-invincible god, rather than hit us over the head with the premise.

All the primary shapes and colors emphasize Thor's power and build: his exposed arms and wrist bands emphasize his musculature, and the pointed shoulders and raised cape accentuate his already broad frame. Even the shape of the hair hugs the outline of the head to suggest both a powerful and royal feel.

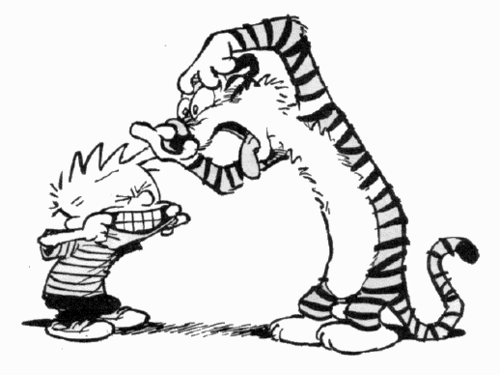

I'm counting these guys as one design, as one really doesn't work without the other. The beauty of Calvin & Hobbes is that they contrast so well, and their design tell us not only about themselves but about each other. Calvin's diminutive, his scruffed hair and dropped face suggests a child at odds with authority, but only through his own chaos and not through direct malevolence. Hobbes towers over Calvin, and often hunches a bit to see him, emphasizing that he is often humoring Calvin's speeches. One thing I especially like about Hobbes is that although he's very cartoony, he still moves and acts like a cat. His body coils and stretches, and his fur will often stand on end in appropriate fashion. It's nice to see a character that isn't just "generic talking animal #357."

You didn't think I wouldn't have a robot, did you? T.O.E., the mysterious sometimes-protagonist from Evan Dahm's Overside stories, is a good example of a character design that isn't tied to a specific costume. There's definitely a color theme and general silhouette requirements (purple and white are dominant, with either a cape, poncho or coat), but it's T.O.E.'s distinctive head that gives him away. His face is a television screen that, in each panel, displays a different image from vintage film or television (despite existing in a completely different universe). It's an unusual flourish that is never explained, which is all the better.

This character reeks mystery, and everything about the design emphasizes that: the head is a simple, recognizable shape, the colors are always subdued and T.O.E. can somehow eat and smoke a cigarette with only a glass screen. When we see T.O.E. we immediately want to know what he's thinking. It's a character that draws us into the mystery of Dahm's stories.

Edward and Alphonse Elric, the beleaguered protagonists from the manga Fullmetal Alchemist, are a wonderful exercise in shape and silhouette dynamics. Al, the giant suit of armor, plays against visual type and generally behaves very timidly, while Ed is the diminutive hothead. The designs are largely about shape contrasts; despite having some spikes and a mean looking head, Al's body shape is bulbous, almost like a baby or toddler, hinting at his childlike nature. The shapes created by Ed's red coat and unusual cutoff jacket make him look shorter than he is, and there are some subtle sharp edges created that suggest his prickly personality.

The designs also tell us about the history of the characters, specifically the premise of the show. Al actually has no body, his soul bound to this suit after their accident. Ed too has a prosthetic arm and leg, which are sometimes (but not always) hidden by his outfit. They're tough kids with a rough history, and it comes through perfectly. Also I'd be lying if I said Edward's prosthetics weren't a partial inspiration for my own protagonist.

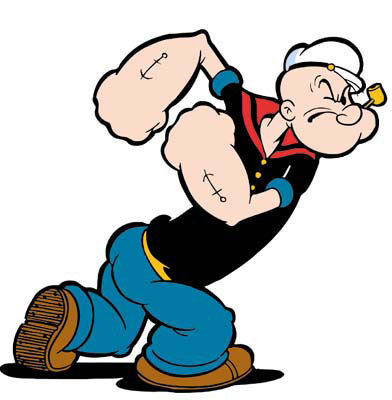

Ugly as sin and built like a bag of hammers, Popeye's visuals communicate so much about his character. His head looks like it was caved in, perpetually in a facial expression of mild annoyance. His limbs look as if they were squashed, emphasizing a scrappy, combative personality, and the second highest contrast area directs us to his bulbous arms, clearly indicating this is a character who does most of his thinking with his fists. Popeye is one of the best examples of design going beyond just what the characters are wearing and into how the characters are physically built.

Mike Mignola is one of my favorite comic artists in general, and nowhere is his solid art sense more evident than in the design of Hellboy. There are some strong, simple shapes going on here, both in the massive stone right hand and in the two "circles" on his head (which are actually shaved down horns). The big, clear shapes make it possible for the little shapes (like the details of the belt and coat) to be very flexible, meaning Hellboy doesn't really need a set "costume" for us to know it's Hellboy.

Mignola avoids the traditional "heroic broad shoulders" design elements for Hellboy, instead pushing the posture and build of a working class man. Fighting monsters is just his job, and there's a tired look in his expression and in the downward sloping shapes created by his coat and body. He's a tough, stoic character, and everything about the design conveys this. If you didn't know any better, you'd think the guy was carved out of rock.

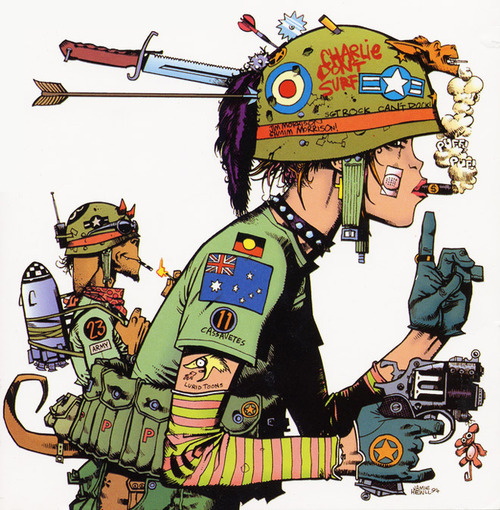

Tank Girl, brainchild of Gorillaz co-creator Jamie Hewlett, is a special case in a couple ways. For starters, she's sadly one of the only dynamically designed female characters in mainstream comics, but also she seemingly breaks some of the rules I put forth at the beginning. Where are the clear shapes, colors and lines? They're actually there, but they're produced by the chaos of the details. I mentioned earlier that we don't really need to know the details of what's on Hellboy's belt, just so long as it's there and there's stuff on it. This concept is taken to its extreme with Tank Girl, who is generally decked out in all sorts of military and punk-themed paraphernalia. The designs are anything but generic, and despite what should be clutter in the hands of any other creator, it holds together. Why?

There's a method to the madness. There are repeating elements like the helment, her hairstyle (within a range), the types of shapes created by the gear and clothing. Similar to T.O.E. earlier, certain types of clothing "fit" the design, while others don't. It also helps that outside of the clothing, Hewlett designed Tank Girl's body and face to resemble a real specific person and not "generic comic book lady." If you've seen his work on Gorillaz you'll know that he does a good job of swapping out costumes on characters without ever losing the iconic "feel" of those characters. You can always tell it's Tank Girl.

It's also not just style for its own sake. Tank Girl's appearance tells us a lot about the character: crude, chaotic, but pragmatic in her own right. This also sets the theme very well for the tone of the comic itself. An absolutely ingenious design that would be a mess in the hands of a lesser artist.

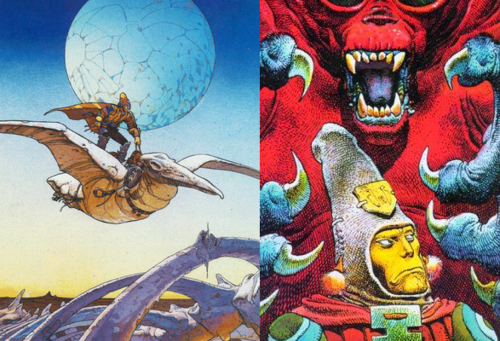

French comic legend Mobeius' comic Arzach has always been near and dear to my heart. Although many in the US may not know it directly, we've seen its legacy, being the partial inspiration for such great works as Nausicaa and Panzer Dragoon. Arzach, like Tank Girl, isn't tied to a specific outfit but rather a style of outfit, the most iconic two elements being his unusually pointy hat and his "stone pterodactyl" steed. However, unlike the intentional chaos of Hewlett's design, every element of Arzach's outfit is carefully chosen: he is a warrior and traveler, and carries with him only items of absolute necessity (aside from the ceremonial trinkets).

Arzach never speaks a word in the series (in fact, it's virtually wordless), flying across a dreamlike landscape in his surreal, partially symbolic adventures. Not only does everything about the design convey "weary traveler," but it also hints at a culture and world we'll never fully know. His tunics are always wide, emphasizing his broad shoulders, and he is covered from head to toe in hand-stitched garb and gear, reminiscent of both Mesoamerican fashion and Natives of the American West. With his pterodactyl, he symbolizes a striking, dreamlike freedom that we want to follow, but the weapons on his person also suggest a warlike past. He is the Odysseus archetype, forever wandering, but also conquering his foes through wits. Arzach is the ultimate visual oneironaut.

Moon Boy is a naked monkey that rides a dinosaur.

I've come to realize, however, that "character design" is itself a fairly massive subject. So now, true believers, we're going to talk about outfits and costumes, which are often a pivotal part of a character's design.

Clothing can convey quite a bit of conscious and unconscious information to the reader, but it should never be doing 100% of the legwork. Body language, shape and overall behavior all come into play when building a character, and the trick is to figure out what clothing can do that these other elements can't. To get started, it's important to ask some basic questions about your character before jumping into costume design.

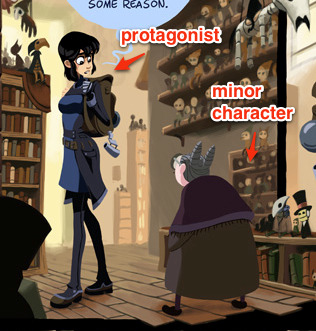

How often does this character appear? Is it a main character or a side one? Primary characters have more complex needs than side characters, which is to say that the more information you have about your character, the more that can be conveyed in their appearance. Additionally, the more frequent the character appears, the more versatile the design needs to be.

If it's a side character that only ever appears in one setting, for example, you need only design the outfit to fit in that environment. If they are a main character, though, chances are you'll need the outfit to mesh with more than one setting.

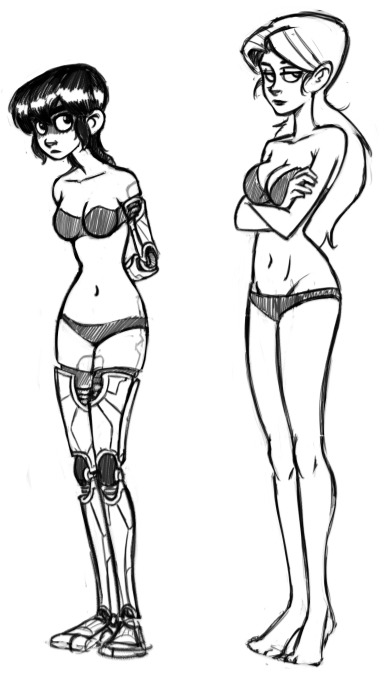

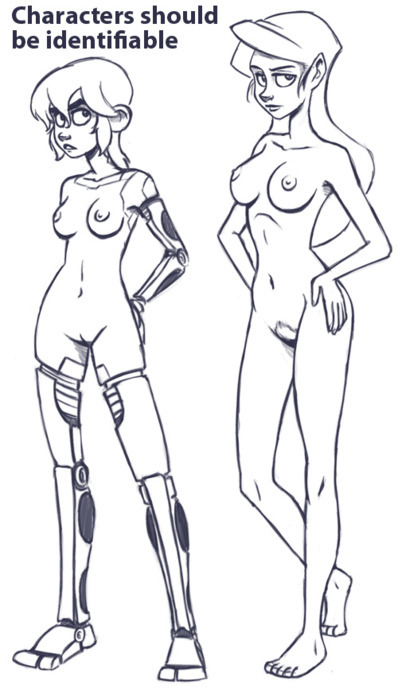

Is your character recognizable without any clothes on? Body types, especially those of the main cast, should be distinctive even without the help of any outfits. The naked form is the foundation of all character design. Before you start dressing your body, make sure it's a body worth dressing.

Once you've sufficiently answered these questions, it's time to jump into the actual design phase!

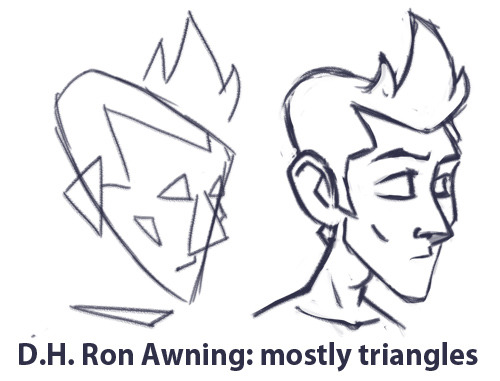

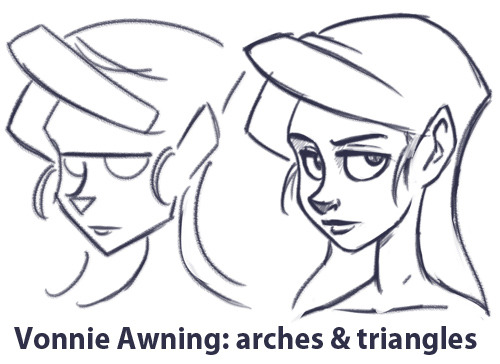

Every character, no matter how complex, should be designed around an overal unique visual shape. This theme should not repeat in any other character. This shape should be readable enough that if you were to shrink all your characters into a super-simplified cartoony state, they should still be distinguishable. Character designs follow a hierarchy: you grab the reader's attention with the most essential information and then invite them to investigate the details. If important elements of your design are only evident in the details, then it needs to be reworked. If your character is not completely distinguishable in silhouette, it needs to be reworked. Detail should always radiate from the core theme.

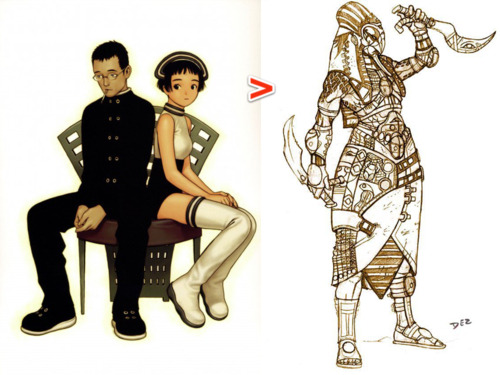

Kim and Vonnie stay distinct in a few ways.

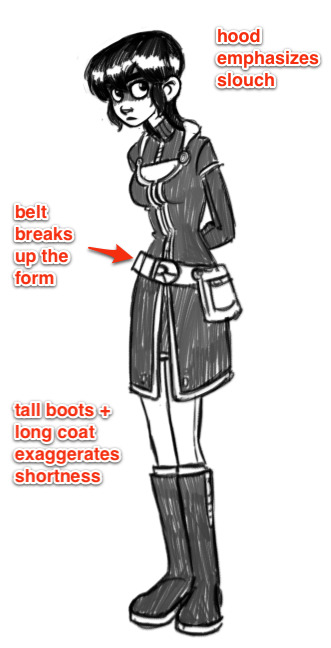

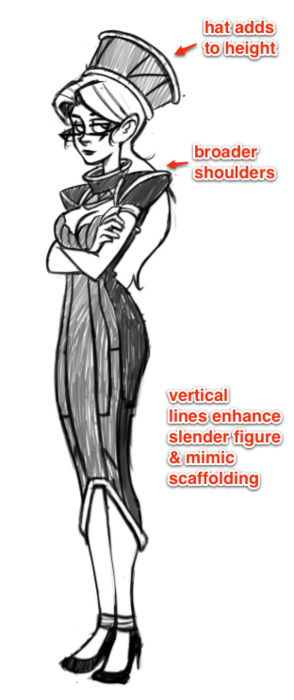

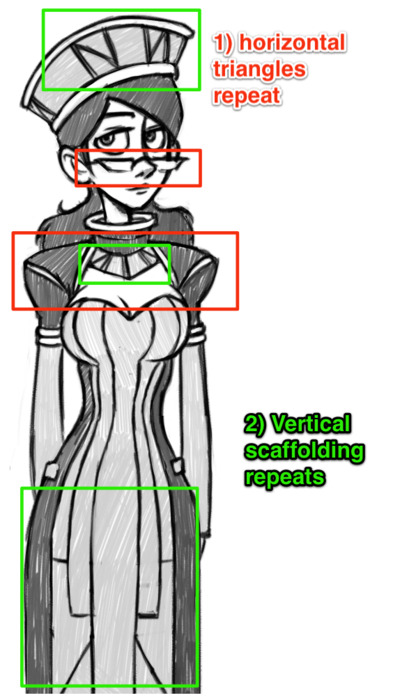

The primary difference in shape between the above two characters is one of curves versus triangles. Vonnie is very angular, and her clothing's angles mimic the scaffolding of an art deco building to emphasize her height and posture. Kim's outfit makes her look shorter, but jaunty. There are a lot of soft curves going on there to make her seem younger and more innocent.

What does your character do? In what way would their clothing reasonably convey how they spend their time? This is an easy question if it's a uniformed occupation, but it certainly doesn't stop there. A more bookish or socially inept character is often prone to mismatched clothing, while a person of a very high social status is often wearing clothing that is physically less practical than those of the working class.

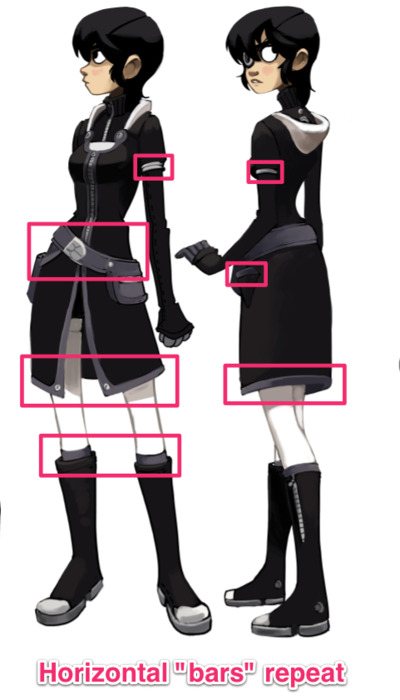

How does your character move? What are their default postures and body language? A good outfit should accentuate the body movements that you deem most important. If a character stoops and hunches a lot, their clothes can augment that behavior. For example, Kim is frequently hunched over, so I tend to dress her with a hood that's shaped to go with poor posture, as well as a repeating "arch" shape to suggest this basic form.

How much does the character wish to communicate with their clothing? Not everyone wears their personality on their sleeve, nor is everyone especially fashion-conscious. Nothing's worse than having a cast where everyone is immaculately dressed and overdesigned. A more outgoing character might be more aware of their appearance, while a more introverted one may be less concerned. To add another layer, a character may dress a certain way to disguise something they don't want to show to others, just as someone might act overconfidently to hide their insecurities. You can tell your audience a lot about your character through what that character chooses to display to others.

Core shapes and patterns should repeat on the outfit. The entire design should exhibit some bilateral cohesion, which is to say if you were to cut the character in half horizontally or vertically, each part should look like it belongs to the other.

As mentioned, Kim has a lot of solid colors and arch shapes which are broken up by fabric and metal seams, with very few sharp edges.

Vonnie, on the other hand, is structured almost like a building, with vertical lines and triangles that take the shape of supporting beams on the surface of her outfit. Her triangles and broad horizontal planes repeat throughout her outfit, including her glasses.

This extends to multiple costumes worn by the same character. Even if a particular character changes clothes, the core shapes should still be evident. Scott Pilgrim is a good example of this. Most of the cast change clothes frequently, but in each scene it's generally easy to recognize the characters by the "type" of clothing they choose. The details change, but the essential shapes do not.

Different colors can imply different moods. "Winter" colors like cooler blues and purples can suggest an introspective or reserved personality, while warmer colors like yellow or red can imply a more energetic attitude. If your character only ever interacts in one type of setting, you only have to worry about how those colors will fit in one environmental color palette. If, however, your character needs to mesh well with more than one environment (as is usually the case with protagonists), you have to make sure your character's colors will fit with multiple settings.

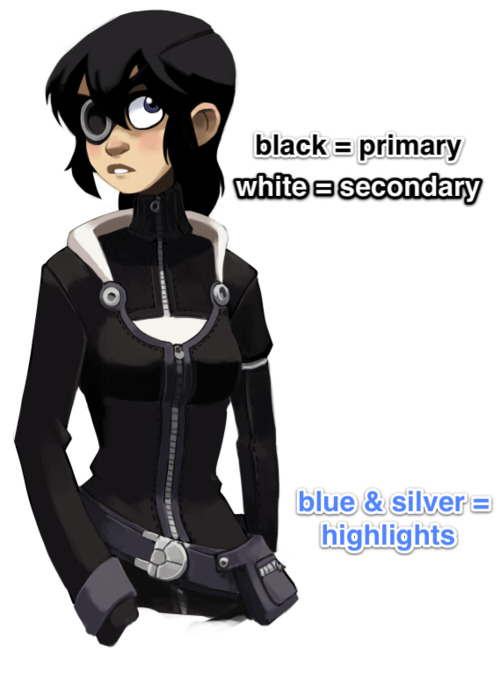

Also, don't be fooled by superhero comics: it's generally bad form to have two dominant colors in a single costume. My personal rule of thumb is to have no more than one prime color in an outfit design, followed by a secondary and then supporting colors.

In the case of Kim's outfit in Dark Science, the primary color is black, with the secondary being off-white. These are then supported by the muted blue and silver accents that appear in both her prosthetics and clothing. Color and value contrast is very important, especially for a main character, which is why Kim's basic palette can be reduced to black and white without losing any essential information.

Vonnie's outfit is more colorful, but less contrasted as a whole. Green dominates and is blocked in by a secondary, warmer black. Green is the complementary color of red, and so her clothes naturally bring attention to her hair and reddish skin tone, inherently highlighting more sexual elements than Kim (whose black outfit essentially matches her hair). White is also present, but it's only a supporting color here.

Above all else, keep it simple. Comic characters are not pin-ups or other illustrations; you have to draw them over and over again, from various angles. If you pile on too much detail, you'll wear yourself out slogging through all the bits every time you have to draw them.

If you follow all these rules, good costume design should create this basic pattern when presented to a reader:

If you stick to these basic guidelines, you'll never fail. Next up on character design: bodies and faces!

Figure drawing is a pivotal tool to any artist, but being able to effectively render humans and creatures is only part of the equation. Even if your draftsmanship is solid, you won't get far if your designs are uninteresting. Effective and dynamic figures are the cornerstone of having compelling characters in pretty much any comic.

The focus of art in general is to generate a particular response out of your audience; the mechanics of what you literally create are often secondary to this goal. Something can be abstract or literal, but the point in both cases is the effect is has on the viewer/listener/reader; the creation itself is a means to an end. In comics, authenticity and realism are not defined by what you are actually drawing, but rather how your drawings are viewed by your reader. In the context of a visual narrative, a simplistic drawing can be "more real" than a more realistically rendered one if that simplistic drawing evokes a more authentic response. A stickman can be a more convincing character than a photorealistic painting; it all depends on how that stickman is conveyed.

When you design your characters, you have an opportunity to both communicate information about them, as well as provide a conduit through which information about other characters and even environments can be shown. Their appearances can augment the actions in the narrative, or even take the place of regular action.

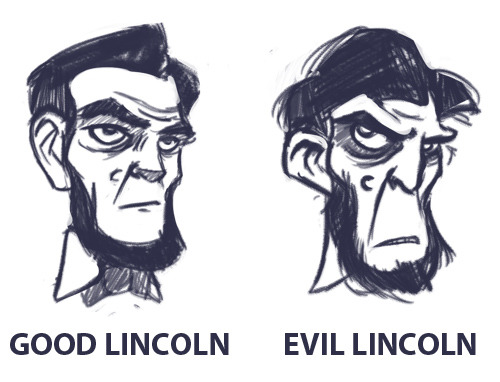

When designing characters for comics, then, it's not universally important to faithfully recreate how people look in real life or even caricature real life. This may sound contentious at first glance. After all, isn't a big part of cartooning exaggerating elements of real life? Certainly, but that's only half of the equation when it comes to visual narratives. A regular caricature is mostly about emphasizing what's visually obvious, and while that's still present in comics and animation, on top of that there's often the need to convey information about the character. Even if you're basing a design on a real person, what you choose to emphasize can determine how the audience views that character. Again, what part of "reality" (in this case people's appearances) you select to share can profoundly change how those characters are perceived.

While they can be very similar, a fundamental difference between the needs of comic design versus animation design is the presence of literal motion.

In animation you can give your character a nervous tick, a particular walking pattern, or any other number of facial and other motion cues to add flavor and depth to a character. However, with the static images of comics, this approach is limited. As such, more pressure is placed upon the designs themselves because they're the primary visual resource the reader has for gaining information about the character. Luckily, there's a plethora of tools at our disposal for doing just that. The shape, size and position of a figure can be designed in such a way that it implies motion. Upturned brows and lips can suggest someone who is frequently bemused, an exaggerated posture can give the impression of a certain type of gait, and so on. And since the reader's eye can dwell on a comic panel indefinitely (at least in theory), there's more freedom to employ subtler facial and body elements to add to a character's flavor.

Silhouettes and overall shape are the first pieces of information to reach the reader, and because of this they will always dominate any character's design. If your silhouette isn't doing its job, the rest won't matter. Starting with a simple, clear shape and working backwards is a good rule of thumb. And while this is naturally easier with monsters and other fantastical creatures, it applies just as much to regular people.

People are not divided into skinny/fat/muscular. While these body states do obviously exist, each of these will still differ from person to person. For example, there's not a single "athletic" body type, but dozens (as this amazing photo series shows). Don't fall into the trap of old superhero comics where everyone looks like a bunch of clones wearing different costumes. People's builds, postures, hands, feet and musculatures are extremely diverse, going far beyond simple factors like age, height and weight.

Your character's motions can inform you quite a bit on how you could design their form. If a character often stoops or shuffles, you can warp his or her spine and posture to bring attention to that sort of behavior. In general, you want the figure to emphasize and accentuate the type of body language indicative of that person. This is really important. In animation, there's a little less of a required connection between body language and design because you can literally show motion, but with comics being a static medium, you have to imply a lot of motion without showing it. Naturally, if your character has a very wide range of motion, your design should reflect that too. Main characters aren't usually designed around a single posture, for example, but side ones often are. In the end, this is all a tool to efficiently communicate information about a character to the audience.

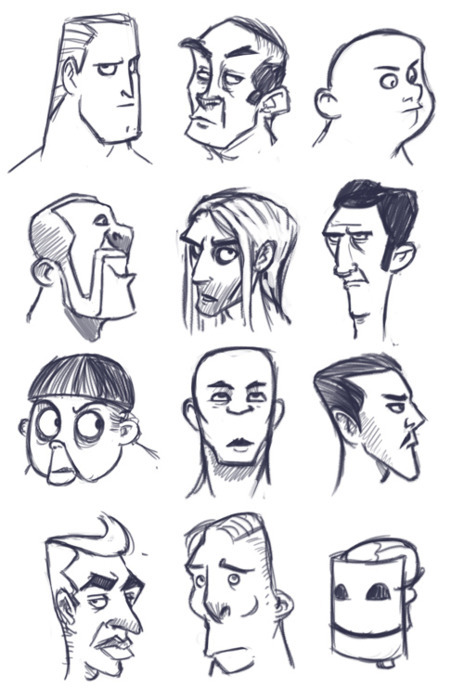

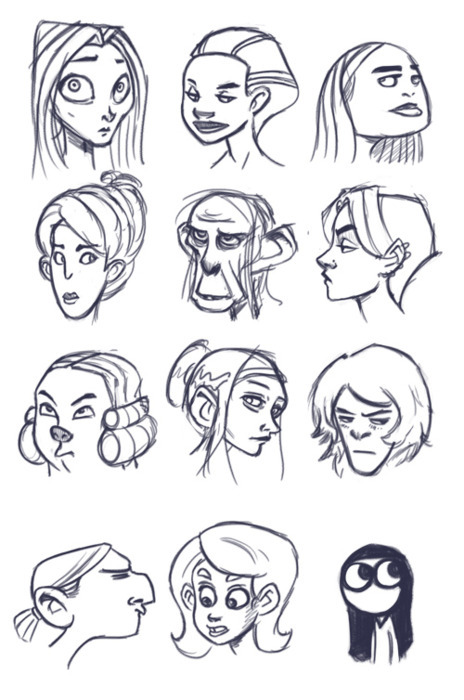

Even more so than with the body, you should be able to reduce each character's head to a fairly recognizable shape. This is the foundation for developing a good head silhouette, which is vital because the focus of a page is often on peoples' faces; recognition should be established on a subconscious level with little to no effort on the part of the reader.

If the reader can't immediately and clearly distinguish who is who without using details, the designs are bad. Also note: using hair alone to distinguish heads is cheating. Similar to the superhero body problem, don't fall into the crappy anime trap of having identical heads that are only distinguishable by their wacky hair. Obviously hair is a component of character design, but to rely exclusively on it is taking a shortcut that only ends in sloppy composition and no variety.

Similar to the Naked Test (which we'll talk more about shortly), you should be able to immediately distinguish all your character's heads without any adornments or hair. Shave ‘em down and compare.

Ears, eyebrows, skulls, eyes, eyelids, noses, cheekbones, nostrils, hairlines, necks- these are all elements that will vary from person to person. Don't be afraid to go beyond normal human proportions. Exaggerating or simplifying to the point of even being a stickman is perfectly fine, so long as it suits what you're trying to do.

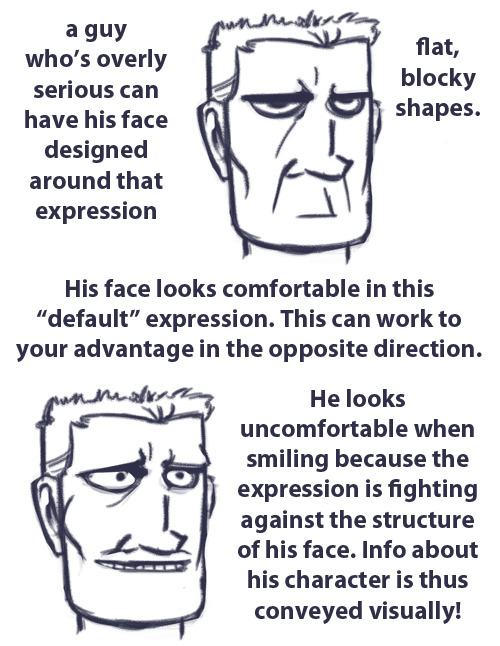

What types of facial expressions and body language do your characters exhibit? Main characters generally require more of a range than side characters, while less three-dimensional characters can be designed to fit only a handful of expressions.

A lot of character information can be shown to the audience this way. Showing rather than telling your readers means you're playing to the medium's strengths.

Once you've designed your figures, we move on to the Naked Test. When developing a cast or even just a couple of characters, they should always be instantly recognizable without the aid of clothing. Even if their clothes have some key distinguishing elements to them (which they probably should), the bodies themselves are the foundation, and if the foundation is too generic, then you're left with a flat design that can't be corrected by adding stuff on top. All the basics should be present at this level: distinguishable silhouettes, unique body types and proportions, and unique facial shapes should all be there to tell your character's story.

Figure drawing isn't easy. Because we're hard-wired to distinguish even the tiniest variance in human appearance, there's a lot of pressure to get figures right compared to other subjects. As such, it's easy to play it safe with conservative designs that don't strain our draw-muscles, but it's important to push past that. Effective and compelling character design is a skill that's indispensable for cartooning of every kind.