SEND ALL FINAL IMAGES & VIDEOS TO: ron.doucet@gmail.com

With your Name and Project Number in the file name:

"your_name_ project#.JPG"

ie: joe_blow_project03.jpg

Content for each week:

PROJECTS = Assignments ranging from various Research tasks, Photoshop tutorials, and Storyboard tests.

STORY STRUCTURE = Reading materials on theory for character development, screenwriting, and plot analysis for film.

LECTURE = Instructor speech at the head of each class discussing the art of visual storytelling.

IPUB Course Outline

The dates below are the Deadlines for each group of tasks.

You may click on the project name to jump directly to the instructions:

< Week 1 - Due: Oct.13 >

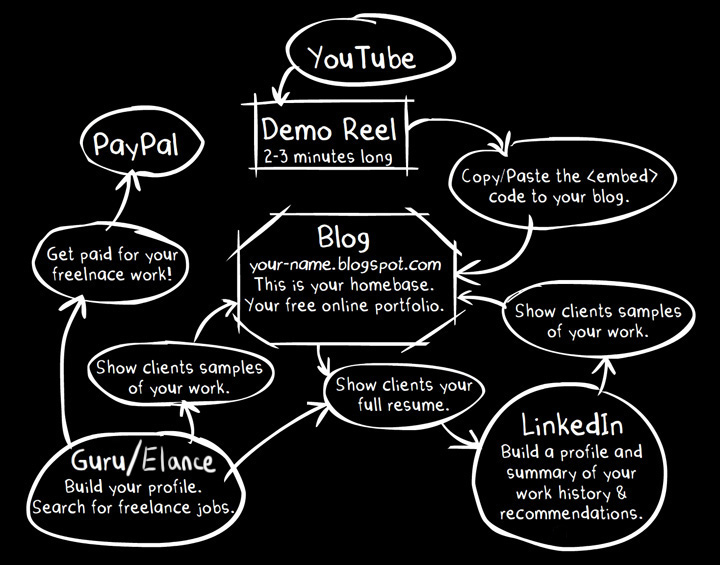

Project #1 - Internet Publishing: Online Portfolio

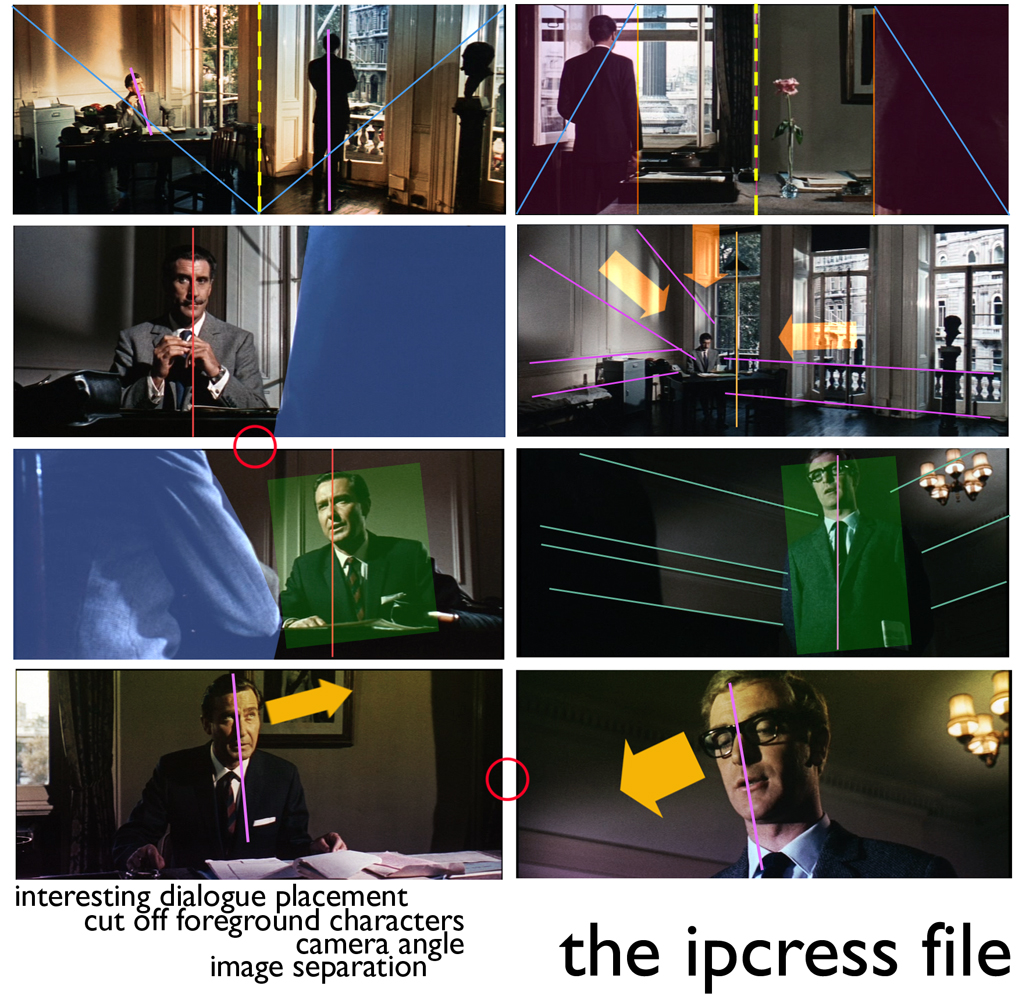

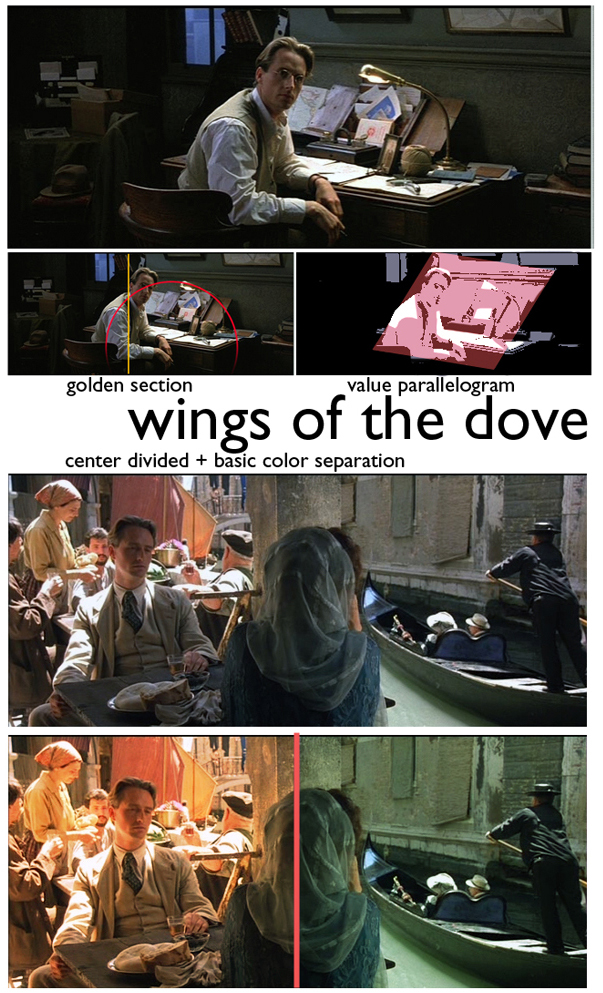

Project #2 - Research: Strong Compositional Style

Story Structure #1: Visual Storyforming

Story Structure #2: Determining The Mind of a Main Character

< Week 2 - Due: Oct.20 >

Project #3 - Research: Triangular Composition

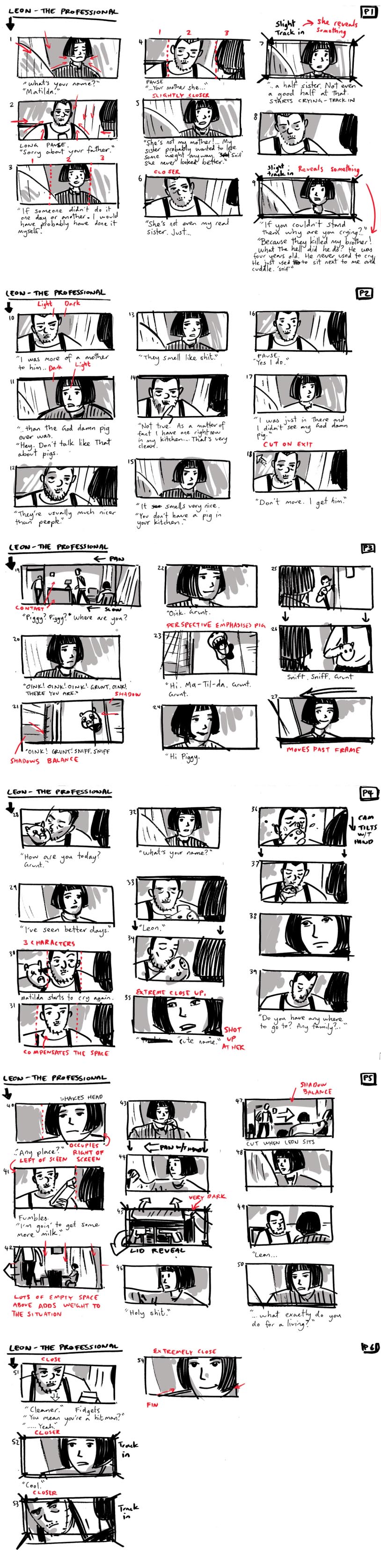

Project #4 - Storyboard Assignment: Leon

Project #5 - Photoshop: Back to Basics (Five Tutorials)

Story Structure #3: What Character Arc Really Means

Story Structure #4: How Your Main Character Solves Problems

< Week 3 - Due: Oct.27 >

Project #6 - Research: Shot Progression

Project #7 - Storyboard Assignment: Incredibles

Project #8 - Photoshop: Character Painting

Story Structure #5: Character Motivation

Story Structure #6: Three Main Aspects of Storytelling

< Week 4 - Due: Nov.3 >

Project #9 - Research: Lighting / Editing / No Dialogue

Project #10 - Storyboard Assignment: Carnivale

Project #11 - Photoshop: Product Ad Design

Story Structure #7: Your Main Character's Most Personal Issue

Story Structure #8: Impact Characters

Story Structure #9: When the Main Character is Not the Protagonist

< Week 5 - Due: Nov.10 >

Project #12 - Research: Movie Trailer / Memento

Project #13 - Storyboard Assignment: Justice League

Project #14 - Photoshop: Print-Ready Business Card

Project #15 - Photoshop: Animation/Rotoscoping & Actions Workflow

Story Structure #10: Consistent Plot Points

Story Structure #11: Personal Tragedy

Story Structure #12: Personal Triumph

< Week 6 - Due: Nov.22 >

Project #16 - Storyboard Test: Duncan's Revenge

Project #17 - Photoshop: Pixel Art

Story Structure #13: End of a Main Character's Arc

Story Structure #14: A Story is an Argument

< Week 7 - Due: Nov.26 >

Project #18 - Storyboard Test: Dysfunctional Dam

Story Structure #15: Two Sides of the Same Coin

Story Structure #16: The Headline of a Story

< Week 8 - Due: Dec.1 >

Project #19 - Storyboard Test: The Diamond

Story Structure #17: The Most Important Event in a Story

Story Structure #18: The Story Limit

< Week 9 - Due: Dec.15 >

Project #20 - Animatic Test: The Diamond

Project #21 - Flash: Button-Activated Motion Graphics in Flash

Project #22 - Flash/Photoshop: Build a Self-Contained Flash Website

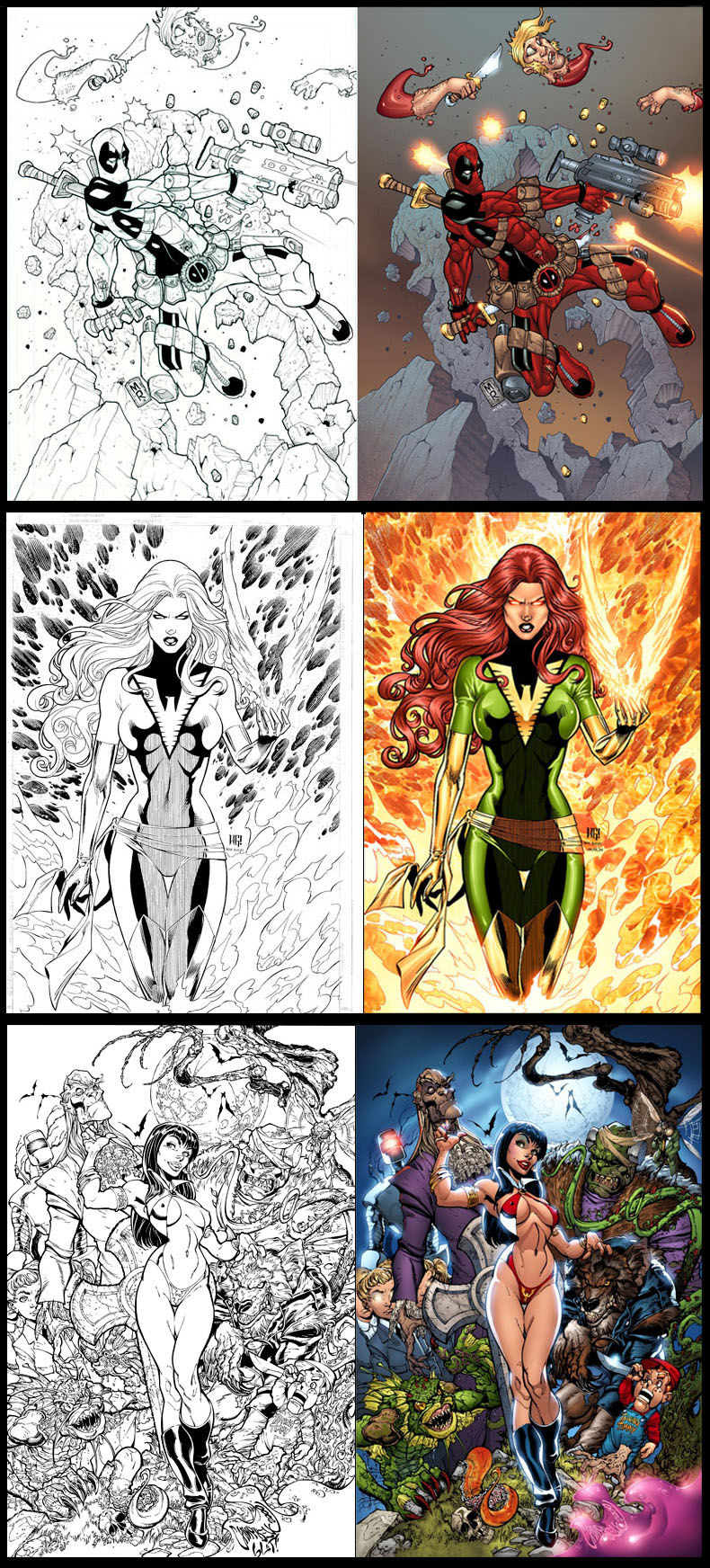

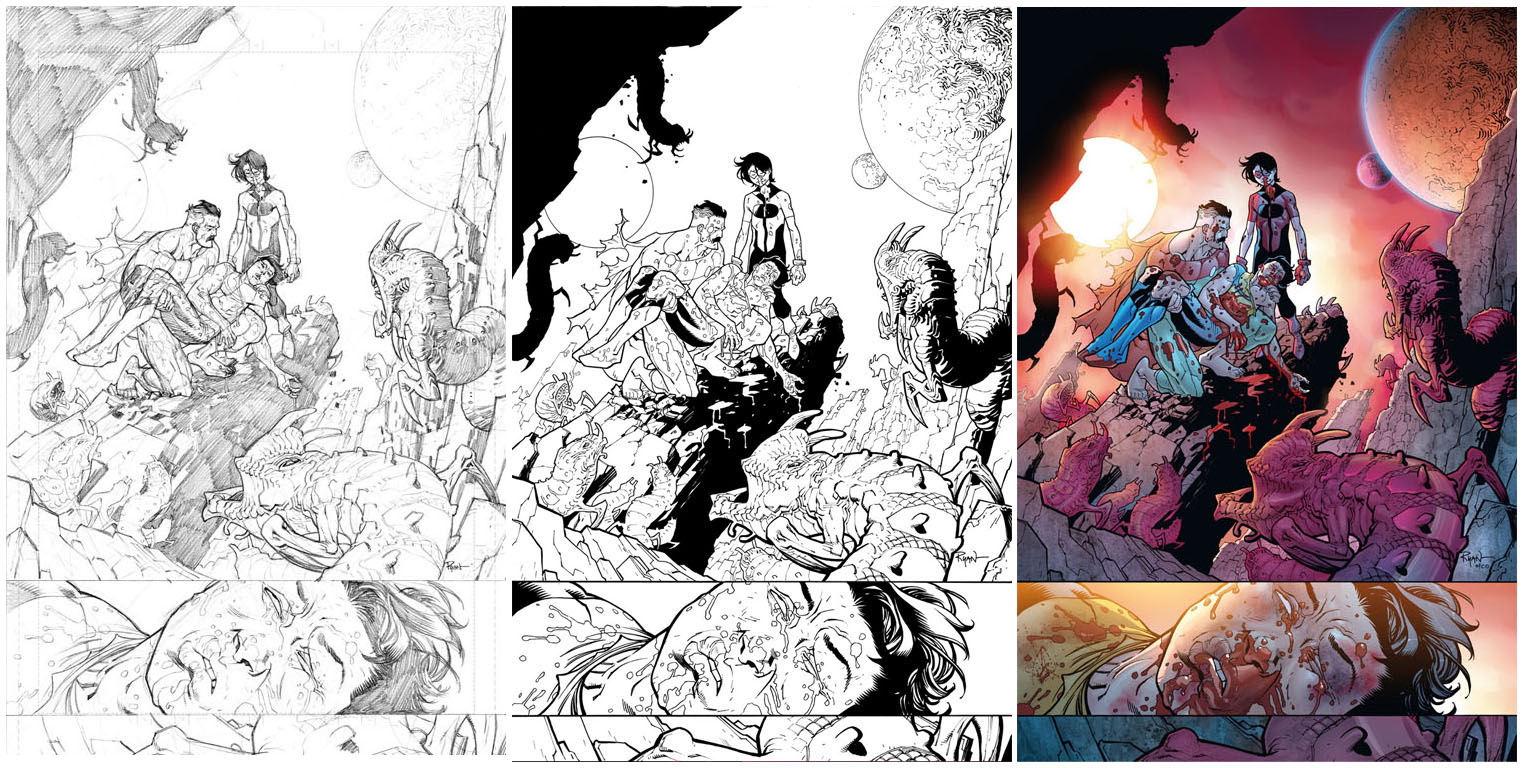

Project Bonus - Photoshop Extra Credit: Professional Comicbook Coloring

Story Structure #19: Story Transformation

Story Structure #20: Subtext

< Week 10 >

Materials for Next Week's Exam

Story Structure #21: How To End a Story

Story Structure #22: Creating Complete Stories (Pixar's Secret)

Story Structure #23: Sophisticated Story Goals

Story Structure #24: The Structure of a Short Story

Story Structure #25: The Development of Character & Story

< Week 11 - Dec.15 >

Final Exam: Composition, Storyboarding, Animation Production & Terminology

Conclusion

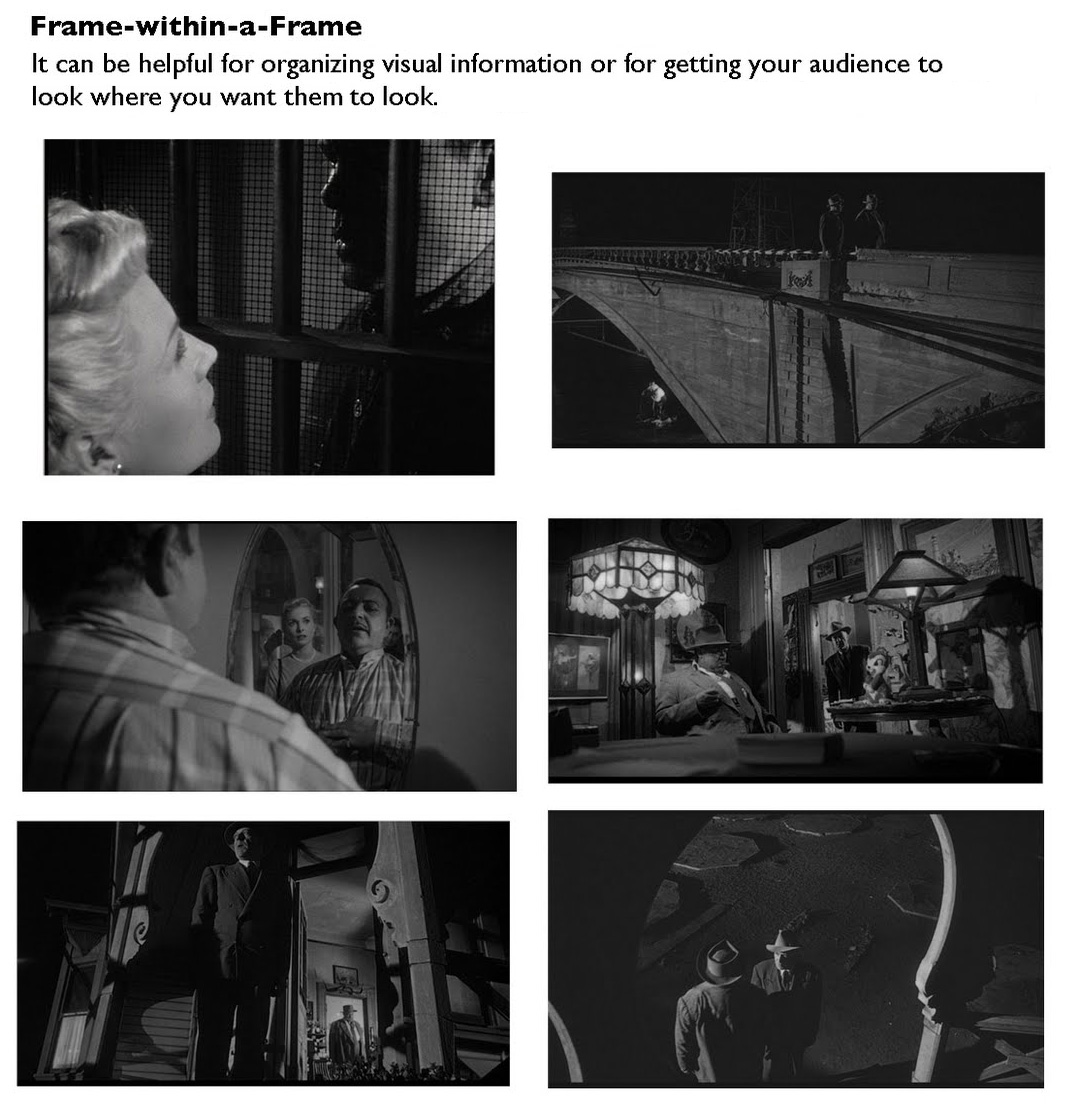

'Framing' can be used within the composition of a shot to help you highlight your main point of interest in the image and and/or to put it in context to give the image some depth.

It also applies in filmmaking:

The perspective that a shot is taken from is another element that can have a big impact upon an image.

Shooting from up high and looking down on a subject or shooting from below looking up on the same subject drastically affects not only the 'look' of the image, emphasizing different points of interest, angles, textures, shapes etc - but it also impacts the 'story' of an image.

There can be a fine line between filling your frame with your subject (and creating a nice sense of intimacy and connection) and also giving your subject space to breath.

Focus on the good stuff. Don't include too much. Extra elements can confuse things. Strengthen your subject by eliminating all unimportant components and background clutter. Either technique can be effective - so experiment with moving in close and personal and moving out to capture a subject in its context.

Sometimes it is what you leave out of an image that makes it special.

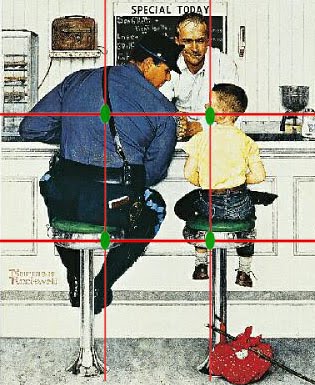

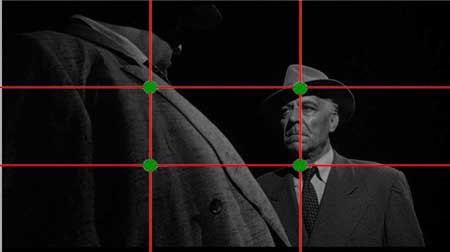

The positioning with elements in a frame can leave an image feeling balanced or unbalanced.

Find your balance. Off-center subjects can be balanced on the opposite side of the frame with leading lines, shadows, and objects in the foreground or background. Balance can also be achieved by creating simple geometric shapes. This makes images naturally easier to decipher and more pleasing to the eye. These photos below are a good example of subjects creating a triangular shape (more on this technique later), which brings strong balance and unity to the image.

It is applied in illustration also:

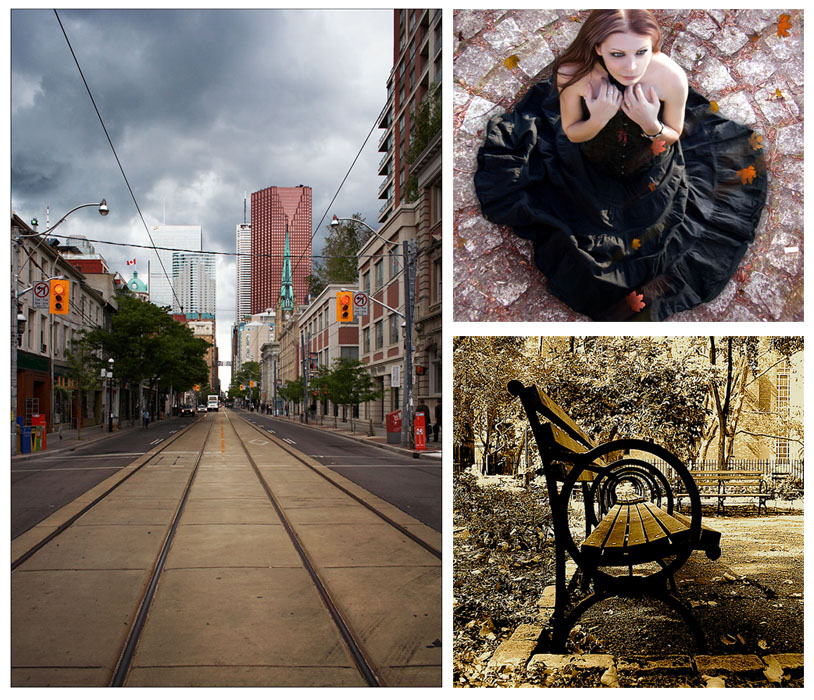

The colors in an image and how they are arranged can make or break a shot.

Bright colors can add vibrancy, energy and interest - however in the wrong position they can also distract viewers of an image away from focal points.

Colors also greatly impact 'mood'. Blues and Greens can have a calming soothing impact, Reds and Yellows can convey vibrancy and energy.

There are patterns all around us if we only learn to see them. Emphasizing and highlighting these patterns can lead to striking shots - as can highlighting ts elemenwhen patterns are broken.

Depending upon the scene - symmetry can be something to go for - or to avoid completely.

A symmetrical shot with strong composition and a good point of interest can lead to a striking image - but without the strong point of interest it can be a little predictable. Mostly, you should experiment with both in the one shoot to see which works best.

Images are two dimensional things yet with the clever use of 'texture' they can come alive and become more three dimensional.

Texture particularly comes into play when light hits objects at interesting angles.

The depth of field that you select when taking an image will drastically impact the composition of an image.

It can isolate a subject from its background and foreground (when using a shallow depth of field) or it can put the same subject in context by revealing it's surroundings with a larger depth of field.

It is applied in filmmaking also:

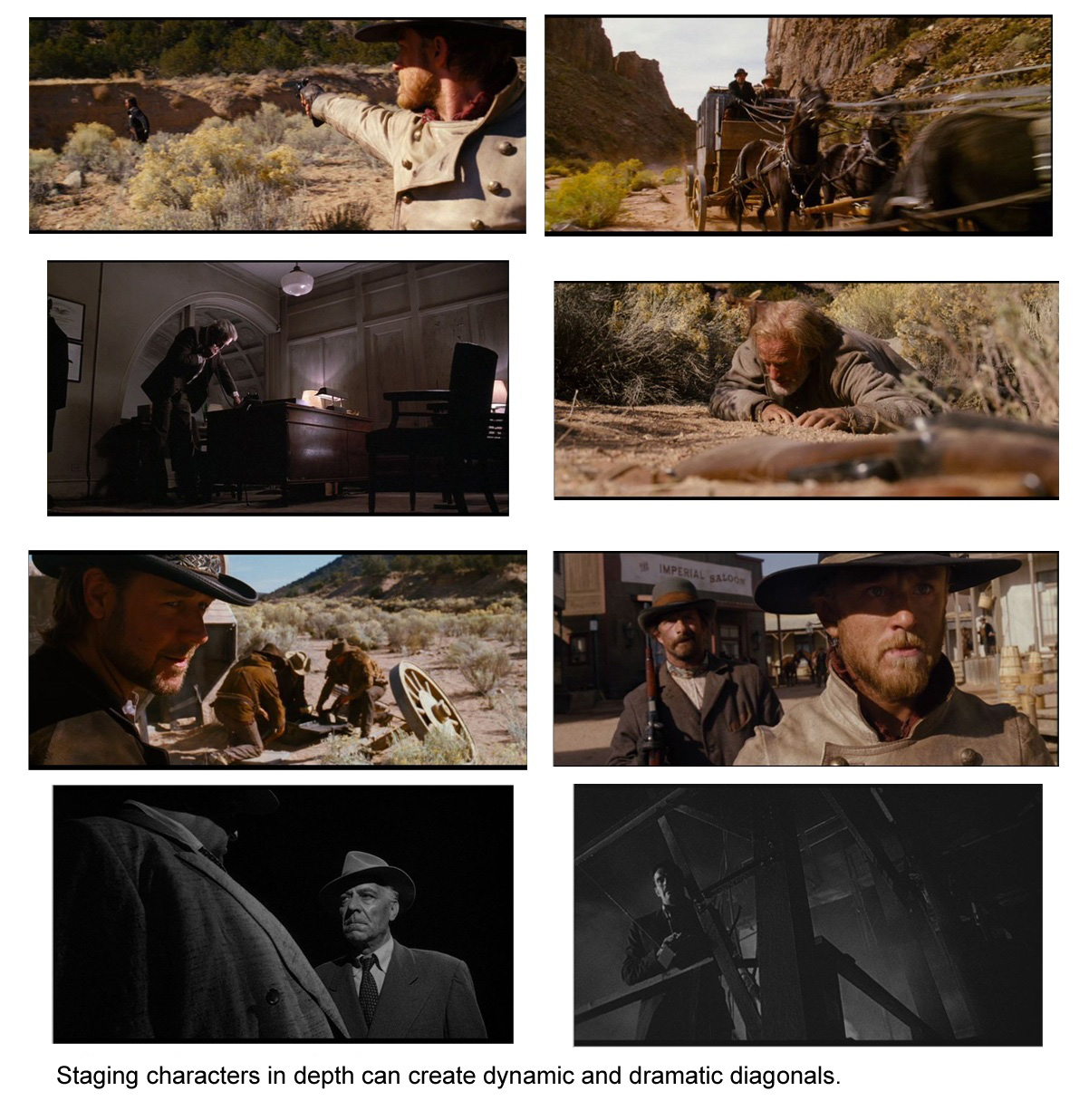

Lines can be powerful elements in an image.

They have the power to draw the eye to key focal points in a shot and to impact the 'feel' of an image greatly. Diagonal, Horizontal, Vertical, d anConverging lines all affect images differently and should be spotted while framing a shot and then utilized to strengthen it.

The key is to remember that in the same way a chef rarely uses all the ingredients at their disposal in any dish - that a photographer (as well as any illustrator of story artist) rarely uses all of the ingredients of composition in the making of an image.

Save & Open up this wood texture from Zen Textures in Photoshop.

Go to Image>Image Size and change the width to 1200px and make sure the resolution is at 72 pixels/inch. This will give us the width that we want for our document.

Using the Type Tool (T), create some white text that will roughly fit the width of the document (leaving some space on the edges). I am using ITC Franklin Gothic Heavy for my font, but anything bold should work.

Using the Crop Tool (C) crop the top and bottom edges so they have a small margin around the text, about the same amount as the sides or a little more.

Click on the eye icon to the left of the text layer to make the text disappear.

Go to File>Save, and save it as a Photoshop file. We are going to be using this file later on in the tutorial.

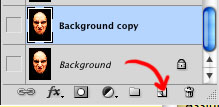

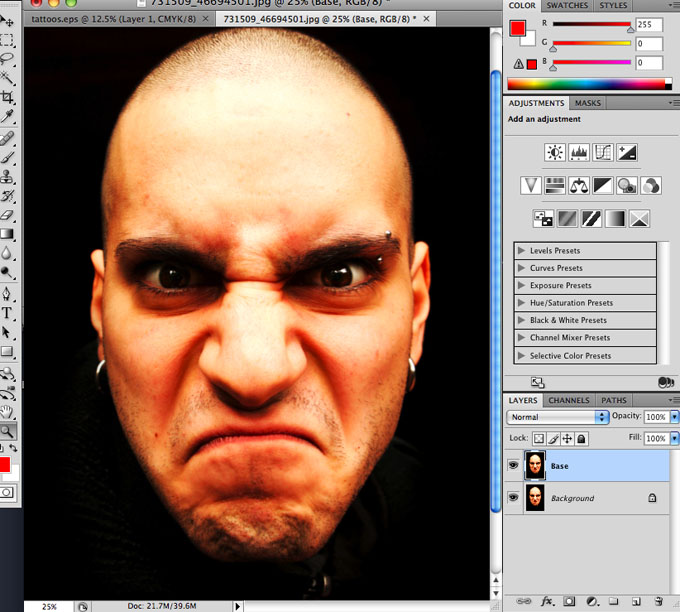

Make sure you have the background layer selected. We are going to duplicate the layer with Ctrl+J.

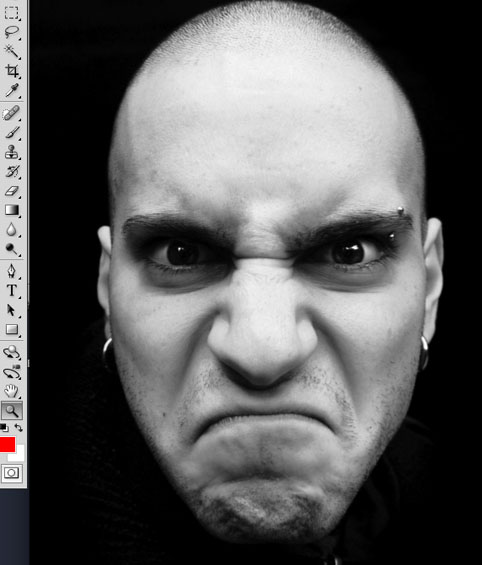

Now go to Image>Adjustments>Threshold. Make your threshold level around 70.

Go into Select>Color Range, and make sure your fuzziness is at 200. Now with the eyedropper click on a black part of the document and hit OK. A marquee around all the black areas should come up.

We want to get the inverse of our selection, so to do that we are going to do Ctrl+Shift+I Now we can click on the text layer and click on Add Vector Mask.

Click on the eye icon next to the text layer to bring it back (if it isn't already), and click on the eye icon next to the black and white wood layer to make it go away.

If we zoom in we will notice that the masked out parts are too sharp to be believable, compared to the sharpness of the wood. To fix this we are going to go into Filter>Blur>Gaussian Blur. Change the blur to about 0.4px.

Now we want to make the edges look a little more believable. First we need to make the mask and the layer just one regular layer, so right-click on the layer and click on Rasterize Layer. Now Right-click on the mask and click on Apply Layer Mask.

Now go to Filter>Distort>Displace and change the horizontal and vertical scales both to 2, click OK. A file browser should come up. Open up the file we saved in the beginning of the tutorial.

If you zoom in you'll notice the edges follow the lines on the wood background.

Drop the opacity of the text down to 80% to give the white part a subtle groove that the wood has.

Now we are going to add some lighting effects to our document to make it look a little more interesting.

First off, lets create a new layer (Ctrl+Shift+N) and move it above the text layer. Click on the Elliptical Marquee Tool (M) and change the feather to 75px. Now click and drag a circle around the text.

We are going to get the inverse selection (Ctrl+Shift+I) of

the circle and fill it with black. Change the blend mode to Soft Light.

Create another new layer (Ctrl+Shift+N), above the text

layer and the shadow one we just created. Create a circle around the text like

we did in step 10 and fill it with an orange color (something like #FF9B0B).

Change the blend mode to Soft Light and the opacity to 50%.

Finally we are going to give our document an overall orange glow. Make sure your foreground is the orange that we used in the previous step and the background is black. Now go into "Create new or fill adjustment layer" (this middle icon at the bottom of the layers palette) and click on Gradient Map. The foreground and background colors should make a black to orange gradient for us. Make sure you click on reverse and click ok.

Drop the opacity down to 20% and change the blend mode to Overlay.

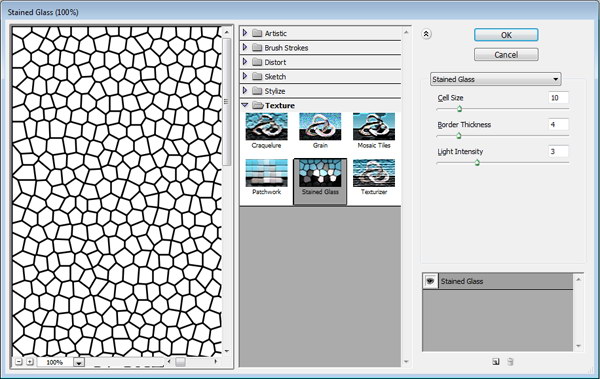

In this simple tutorial we will demonstrate how to create a leather texture from scratch using a few filters in the right combination.

Create a new file with a white background (1600 x 1200 pixels in size at 72 resolution). Set the foreground and background color to black and white by pressing D. Click Filter > Texture > Stained Glass ...and use these settings:

Create new layer and fill it with white. Change its opacity to 50%. Repeat previous filter by pressing Cmd + F. If you want tweak the setting use Cmd + Alt + F.

Press Cmd + E to merge both layers. Click Filter > Noise > Add Noise.

Press Cmd + A then Cmd + C to copy all to clipboard. Open Channels panel and create new channel. Then Paste (Cmd + V).

Click RGB channel to return to Background layer. Click Edit > Fill, choose Use: Color and pick your color. You can use any color you want, just make sure it's dark enough for the next filter.

Click Filter > Render > Light Effects. In Texture Channel choose Alpha 1.

The default light is too dark. You need to add more light sources by dragging the lamp icon to the preview box. Set its type to Omni.

Click OK and the result should look something like below.

Change the background and foreground color to white and black by pressing D then X. Activate the Gradient Tool, choose radial with white to transparent. Create a new layer and draw a gradient.

Change opacity to 4%. This will add subtle lighting to the leather.

The Lighting Effects filter will add a small border to the image (just a few pixels). To remove it, click Image > Canvas Size and reduce the size of the image.

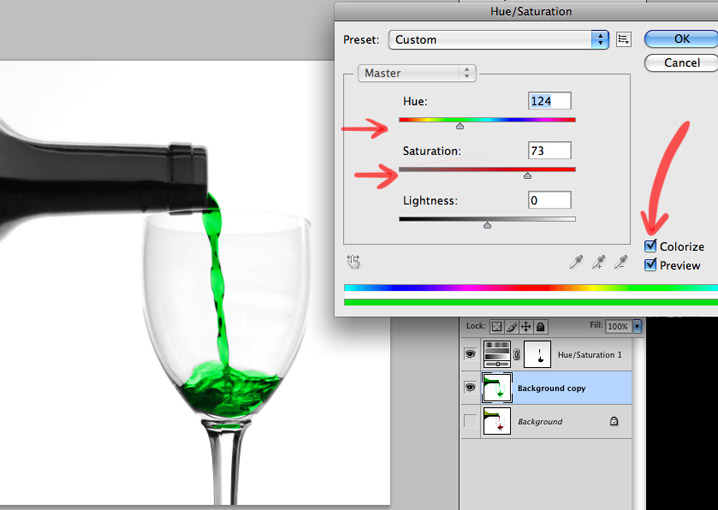

You can change the color by adding an adjustment layer Hue/Saturation. Check colorize and move sliders until you satisfied with the result.

That's it. I hope you like the final result and have learned some new techniques from this short quick tip tutorial.

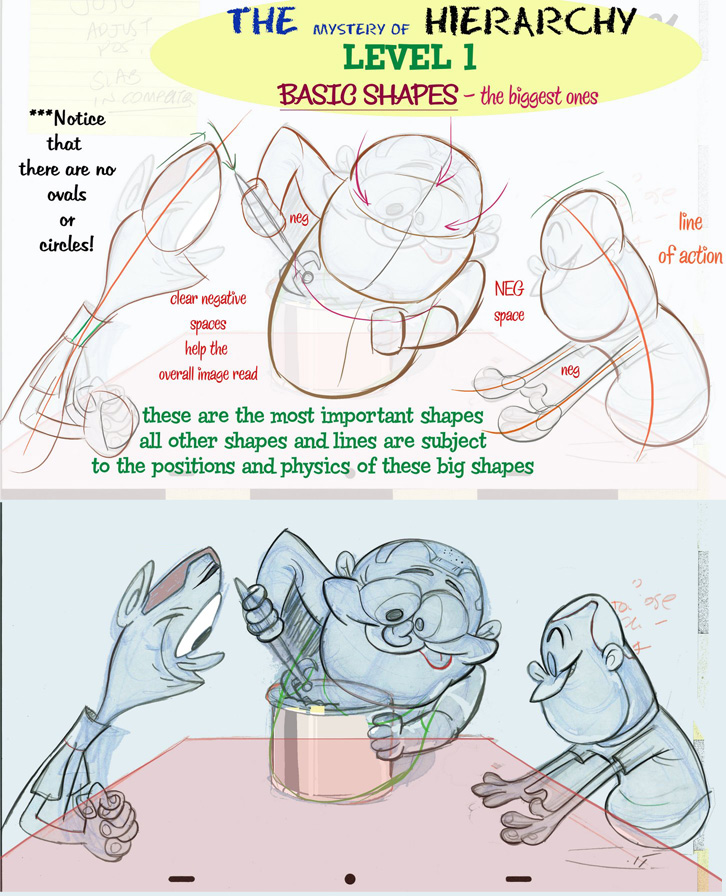

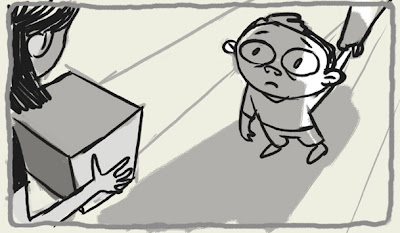

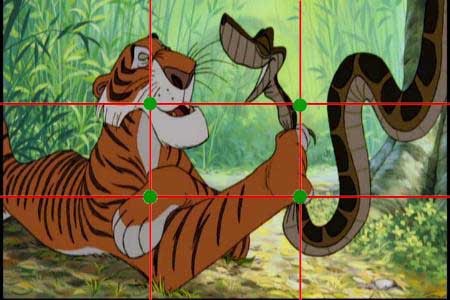

Instead

of starting a picture with small details, they instead have to plan a big

visual statement that reads clearly and simply.

The

overall image above is broken into 4 basic shapes. Then each major shape is

again broken into subdivisions.

Then

the next level.

Someone

with less control would get all absorbed in the details early on. Maybe he'd

start by drawing a bunch of individual leaves and hope they ad up to an overall

tree shape. Or he might do a wild pose of the character - with all the limbs

sticking out in every direction, and no overall silhouette.

Good

storyboard artists have to have this kind of self-control - to avoid getting lured into the details too early. Artists often struggle with composition, because they want to get right to the character first.

Here's

another example. The characters look great, but they fit perfectly into a much

simpler framework, which helps them read well.

Ranger

Smith, Cindy and Baba Looey act as one form, that in turn fits into the bush

shape behind them. They together are well separated from Yogi, who is the focus

of the picture. Boo Boo looks up at Yogi and is framed by the bushes behind

him. If all the characters were evenly spaced and the same size, the picture

would be confusing and wouldn't draw your attention to anything in particular.

The

characters and BG also frame the skywriting plane in the BG.

You

can see this definitive arrangement of shapes in all of Eisenberg's comics.

Great

illustrators like N.C. Wyeth use these exact same principles; only apply them

on more complex levels with more complex drawing:

You

can still see the big shapes dominating the compositions, and the details being

subservient to them through many levels.

Frank

Frazetta has beautiful intricate details in his work, but his images also are

stunning simple compositions. The whole image is a design. He became a master

at composition and hierarchy - so much so that his work is almost a caricature

of artistic control. Everything in his images fits so perfectly together that

it's almost unnatural - even though he is using guidance from a great

observation of nature.

The

differences between Frazetta and good animation cartoonists are in individual

skill and style, not so much in fundamentals. Frazetta can draw much better

than most cartoonists (or anybody else). He also can control more levels of complex

detail, and difficult elaborate structures - like anatomy.

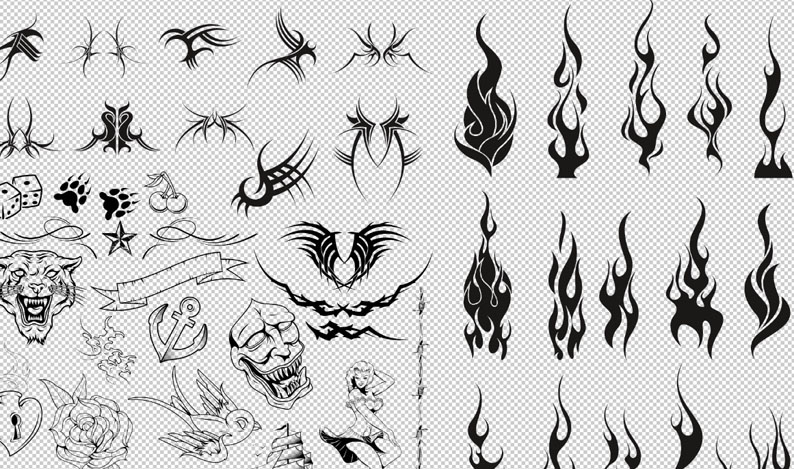

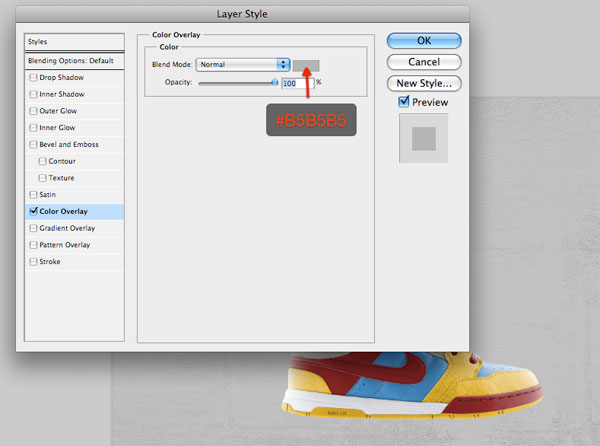

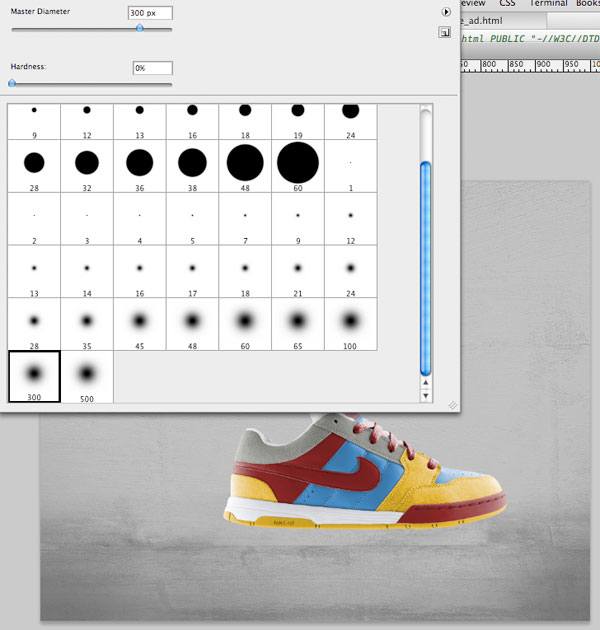

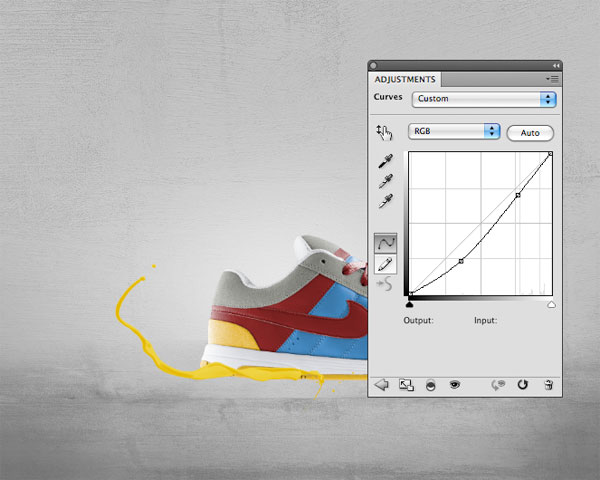

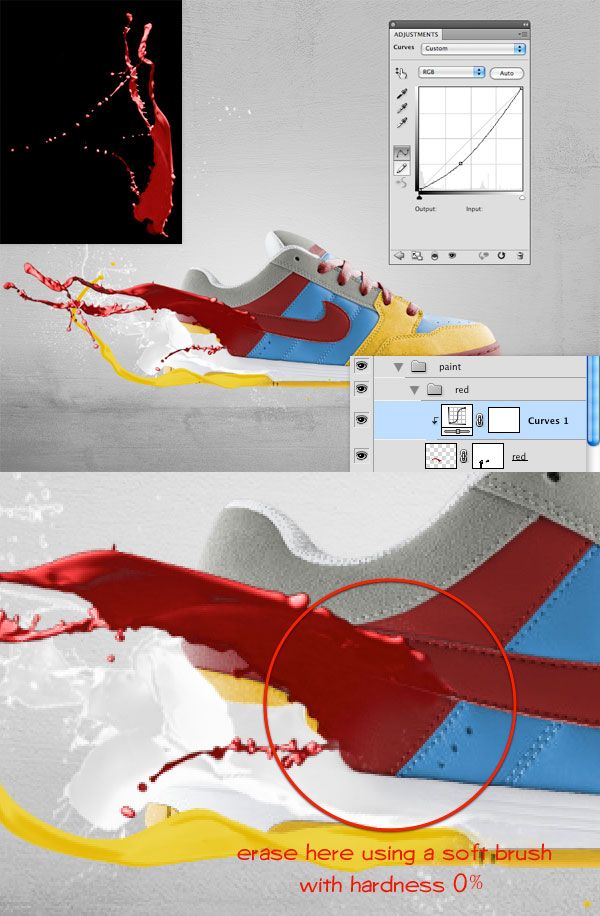

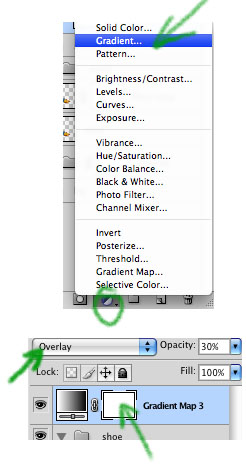

Here is the ad poster design we will create. For this tutorial, I've chosen a classic Nike shoe. You can use any kind of product image and create the same effects. If you want to work with this particular shoe open it from the zip file you just downloaded. If you want to pick your own product make sure you extract it so that it is isolated on its own layer without a background.

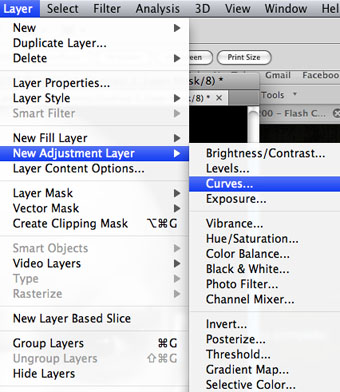

Once you've decided on the poster design's subject (i.e. what article of clothing, electronics or product you'll be featuring), Use the Pen Tool (P) in Paths mode to select around the edges of the shoe. Press Ctrl(or Cmd on a Mac) + Click (on the layer) to make a selection (or, on your photo, right-click inside the path and then choose 'Make Selection' in the menu that appears), invert the selection (Select > Inverse) and hit Delete to remove its background. This process should isolate our subject for our product ad and prepare us for the next part. Create a new document (Ctrl+ N) in Photoshop. Mine is 1000x800px with a white background. Once your new PSD is created, paste in the shoe. The focus of our work is the product (the shoe); this is why we will create a soft, unobtrusive background with the goal of making the piece focus into the subject. Extract & Open the texture files from the zip file you downloaded, I picked the second one here, select it, and copy/paste it into your document with ypur product (Ctrl+A Ctrl+C go to your work file Ctrl+V). Press Ctrl+T to activate the Free Transform command and reduce grunge texture's image size to fit our canvas. Place the texture's layer between the shoe layer and the default white Photoshop Background layer. Desaturate the texture by selecting its layer in the Layers Panel and pressing Shift + Ctrl+ U (or choosing Image > Adjustments > Desaturate). After desaturating the texture, switch its layer's Blend Mode to Overlay. The background will now become completely white because it's overlaid into the white Background layer, but don't worry: we will fix this using blending options. Right-click on the Background layer in the Layers Panel and select Blending Options. The Layer Styles dialog window will pop up. Here, add a grey (#b5b5b5) Color Overlay. After you have added the Color Overlay layer style, reduce texture layer's Opacity to around 30%. Tip: When you resize a texture, lots of small details will be lost. To enhance details on your texture, you can use the Sharpen filter (Filter > Sharpen > Sharpen) if you want. Now that we have a nice grungy background, let's create the floor for our subject. Duplicate the texture layer by right-clicking on its layer in the Layers Panel and choosingDuplicate Layer in the menu that appears. Since the Blend Mode of the original texture layer is set to Overlay, we need to set the Blend Mode of the duplicated layer back to Normal. Afterwards, Press Ctrl+ T to activate Free Transform and then drag down the top-center transform control to reduce the texture's height as if we are squashing it down - in this way, we are creating the idea of perspective. Next, grab the Burn Tool (O) from the Tools Panel to darken parts of the floor; in particular, we want to darken the bottom corners. The floor is still too prominent - we want it to be more blended with the textured background. In this way, we give depth to the image and the floor looks less distracting. Use the Eraser Tool (E) to remove the top horizon (the top edge of the floor). Choose a large, soft brush with Hardness at 0% for your Eraser Tool. Tip: If you prefer, use a layer mask and a black brush on the floor layer to achieve the same result. To complete the floor, create a new layer on top of it, select a black, large, soft brush and paint over the corners to darken them. Afterwards, reduce the Opacity of this layer to 10%. The aim of this step is to drive the viewer's attention to the center of our canvas where we've placed the product. The background is almost complete. The last touch is a light effect behind the shoe. It's my habit to enhance subjects with light effects - it's a way to embellish the product and draw even more attention to it. Don't forget that the aim of an ad poster is to sell, so we have to do our best to increase the customer's desire to buy it. Even just a few details can make the difference between them looking longer or looking away quickly. For the light effect, start by creating a new layer that is immediately above the background layers. Then use a big, white soft brush and click once on the canvas with the Brush Tool (B) to create the light effect. We will now integrate paint effects into our composition. We will place them on the back portion of the shoe, making it look like as if paint is melting the shoe (hence, "toxic paint"). In order to achieve this result, we need to determine what colors to use by sampling parts of the shoe with the Eye Dropper Tool (I) and we also have to play with their colors to match shoe colors. For this effect, you will need to extract the Paint Tossing Pack from the zip file downloaded earlier. Let's start from the bottom of the shoe (the yellow area). The best option would be to find a paint effect with a simple horizontal-oriented shape. This one (which is part of the Paint Tossing Pack) is perfect for our needs: Open this texture in Photoshop and double-click on the default white Background layer to unlock it. Grab the Magic Wand Tool (W), select the white area by clicking on a white area in the canvas (which should automatically select all white areas), and hit Delete to remove the background. Drag the prepared shape into the main canvas. Activate the Free Transform command (Ctrl+ T) to rotate and resize the paint shape. Position it on the yellow sole of the shoe. Now we have to make the paint shape yellow; we will use two adjustment layers for this. With the paint shape layer as the active layer in the Layers Panel, choose Layer > New Adjustment Layer > Gradient Map. In order to affect only the paint (and not all the layers that are below the Gradient Map adjustment layer), create a clipping mask (Layer > Create Clipping Mask) on the adjustment layer. Set a color gradient going from a dark yellow (#e9c603) to a lighter one (#f3df71). The paint's color is still too light, so use a Curves adjustment layer (Layer > New Adjustment Layer > Curves) to darken it a little bit so that it matches the yellow color of the sole of the shoe. Finally, create a layer mask on the paint shape, grab a soft, black brush and then use the Brush Tool (B) to erase a small area on the right side of the paint shape so that it looks as if it belongs to the shoe. Other "toxic paint" effects are created using the same method, but applying different adjustment layers. For the white paint shape, I've applied a Black & White adjustment layer to desaturate the shape and a Gradient Map adjustment layer going from a light grey (#d7d7d7) to white (#ffffff) to color it. For the red paint, I've chosen a red paint shape from the Paint Tossing pack that's rotated horizontally with Free Transform. To darken its color, I've applied a Curves adjustment layer. For the grey paint, I've increased its brightness to 70 using a Brightness/Contrast adjustment layer (Layer > New Adjustment Layer > Brightness/Contrast). Secondly, I've added a Gradient Map adjustment layer going from a dark grey (#525252) to a lighter grey (#e6e6e6). Finally, for the last paint effect, I've applied the same adjustment layer used for the Bottom White Paint. Select the shoe layer and create a layer mask on it by clicking on the Add layer mask button at the bottom of the Layers Panel. Once the mask is created, you can use a black, soft brush for the Brush Tool (B) to erase parts of the shoe without losing any pixels (which is great if you want to modify your work, go back to its original state, or if you make a mistake - just delete the layer mask). This will create the illusion of the paints being continuously connected to the shoe. Create a new layer below the shoe layer; we will add a soft shadow effect for the shoe on this layer. The best way is to grab a soft, black brush and paint at the bottom of the shoe. Once you have painted the areas where the shadows are, decrease the layer's Opacity to reduce the shadow's prominence. Create more shadows, but don't just use a single layer to create shadows. I suggest creating different spots on different layers. In this way, you have more control, you can create depth, and you can tweak individual shadow layers to produce interesting outcomes. For example, you can reduce the Opacity of each layer at different values so that the shadow looks more realistic. The ad poster is almost complete. Colors interact in a way that I like. It's simple but vivid at the same time. It's also directed and focused, as a product ad design needs to be. Observing the current composition, I think there's nothing left to change. What we can do better, though, is increasing the poster's color contrasts. To do this, create a new Gradient Map adjustment layer on top of all the other layers. Set the gradient to go from black to white and then switch the adjustment layer's Blend Mode to Overlay. Finally, reduce the layer Opacity until you're satisfied with color contrasts in your composition, an Opacity value of 30%, seems to work well here. To style it up a bit, just add the Nike logo (or ANY logo you wish), in this case I downloaded the logo on a white background, placed it in the document, set the layer to Multiply, and we're done.

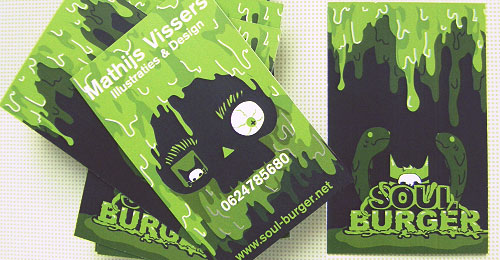

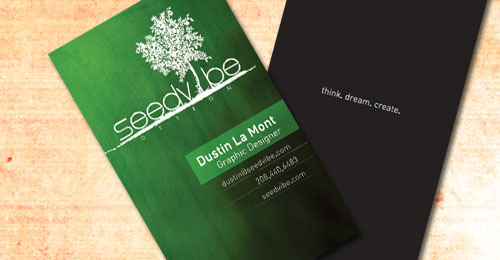

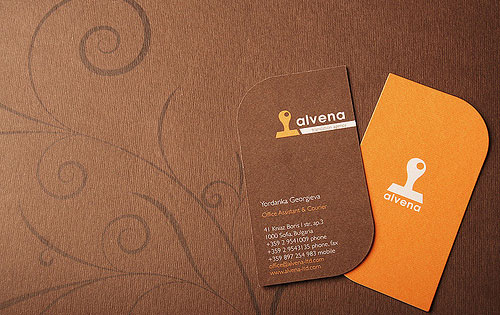

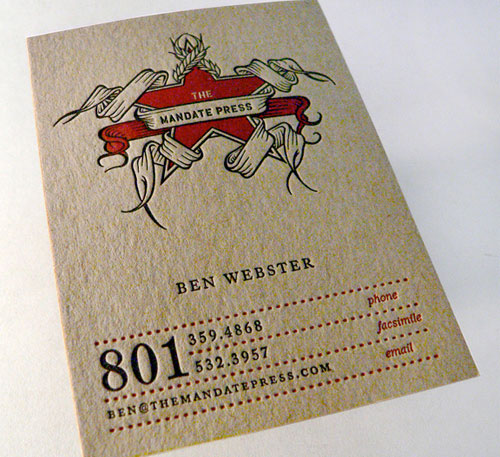

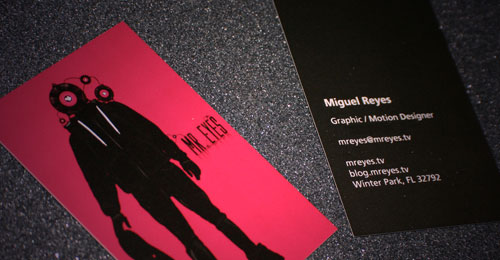

by: Mathijs Vissers by: Humanot by Sorin Bechira and Adrian Labos by Design Ranch by: SeedVibe Design by REACTOR by: Edustries by JS3 Design by: emrah serdaroglu by Light PLague by: Matthew James by Design Ranch by: Jason Woan by Depux by: Fuelhaus by: Matthew Inman by: Muku Studios by Ethan Martin by: Richard Cardona by: John Leschinski by: studio RVOLA by: Thomas Champion by: LiFT Studios by: Baris Celebi by: Alex ElChehimi by: deskfolio.com by: Ahmed Murtaza by: [gb] Studio by: Cihan by: Romi Dumitrescu by: Versł░til by: Jungle it! by: Four Players by: SolarisMedia.net by: Lukł░ë░ Strnadel by: Miguel Reyes by: Ben Falk by: Davier Interactive

Two other tools that will come in handy are the marquee tool You'll also use the eyedropper Finally, make sure you learn the shortcuts. They can save you a lot of time and energy. A good one to know is "X", which switches your primary and secondary colors. I know what you're thinking - this seems too easy to even bother with! But with these 8-bit graphics-style pixels, even straight lines can be problematic. What we want to avoid are "jaggies" - little breaks in the line that make the line look uneven. Jaggies pop up when one piece of the line is larger or smaller than the surrounding pieces. For curvature, make sure that the decline or incline is consistent all the way through. In this next example, the clean-looking curve goes 6 > 3 > 2 > 1, whereas the curve with the jaggy goes 3 > 1 < 3. Being comfortable making any line in pixels is crucial to doing pixel art. Later on, we'll learn how to use anti-aliasing to make our lines look more smooth. 1. What will the sprite be used for? Is this for a website, or a game? Will I have to animate this later, or is this it? If the sprite will be animated later on, you may want to keep it smaller and less detailed. Conversely, you can pack as much detail into a static sprite that you will never have to deal with again. But think about where the sprite is going to go, and what will work best. 2. What constraints are being placed on me? Earlier, I had said that color conservation is important. One of the reasons is that, especially if you are working on a game, your palette of colors may be limited. Also consider the dimensions of your sprite and how it will fit with its surroundings. For this tutorial, I wanted to make sure the sprite was rather large so that you could clearly see what was happening with each step. To that end, I decided to use the Lucha Lawyer, the ass-kickin'est wrestling attorney around, as my model! You can create any object, character or creature you wish. There are two ways to approach the outline. You can draw the outline freehand and then clean it up, or you can start by placing the pixels as you want them from the start. You know, like "click, click, click". I think which approach you should use depends on the size of the sprite and your skill at pixelling. If a sprite is very large, it's much easier to sketch the outline freehand to get the general shape and then clean it up later than to try and get it right the first time through. In this tutorial, we're creating a fairly large sprite, so I'll demonstrate the first method. It's also easier to illustrate with text and pictures. Load the default Square Brushes from the Library that comes with Photoshop, this will give you that hard-edge small square pixel line you want. Even large sprites never usually exceed 200 by 200 pixels. The phrase "doing more with less" never rings more true than when pixelling. And you will soon find that one pixel can make all the difference.

Project #11

Photoshop: Product Ad Design

Resources

Step 1: Preparing the Product

Step 2: Create a New Photoshop Document and Place the Subject

Step 3: Add the Background Texture

Step 4: Enhance the Background Texture

Step 5: Create the Floor

Step 6: Create a Light Effect Behind the Shoe

Step 7: Create a "Toxic Paint" Effect

Prepare the Yellow Paint Shape

Bottom White Paint

Red Paint

Grey Paint

Top White Paint

Step 8: Refine and Enhance the Shoe with a Layer Mask

Step 9: Add Shadows on the Shoe

Step 10: Perform Final Refinements

That's it!

Story Structure #7

Your Main Character's Most Personal Issue

To get a different perspective on what is really going on in your story you need to view your story (the script, the storyboard) and impartial and unbiased, this can be difficult to do, the more involved you are in the development of the story, both how it is written and how it is visually displayed, the more difficult this can be. You should not change how these main concepts of storytelling work, just the way you approach them. In doing so, you'll find different questions to ask yourself about your story itself.

The Main Character's Throughline is the one spot where you can get a broad overview of what is really bothering the main character. While the further down the chart you delve the more precise you can be about your writing, you also risk confusion as the differences between things gets smaller and smaller. Better to stay at the top until you really feel confident with the kind of issue your Main Character is dealing with.

Think of your Main Character's most personal issue - that issue that they would take with them into any story, regardless of what happens around them. Got it? OK, now ask yourself these questions:

* If her situation improved, would she be happier?

* If her mindset improved, would she be happier?

* If the way she engaged in activities improved, would she be happier?

* If the way she thought about things improved, would she be happier?

All of these may pertain to your Main Character, but only one of them will feel really right.

Perhaps she's an underpaid factory worker who thinks only the rich can get richer. If she was paid a decent rage would she be better off? Not really, because it wasn't her situation that was holding her back, it was her defeatist attitude that class dictates providence.

Or maybe she's a struggling pianist stricken with such an awful fingering technique that she spends most of her days trying to bury her love for classical music. Wouldn't she be happier if she just realized things are what they are and instead embraced her passion for Bach? No, she'd continue to be miserable with every missed key. On the other hand, with a little extra time spent practicing her scales, she might find herself loving the classics even more.

Asking yourself these questions will help you nail down the source of your Main Character's issue. With that information in hand, you can then spend time writing scenes that develop on that issue and either have your Main Character work through resolving it or leaving it to fester. Either way, you'll have the confidence knowing where your Main Character is coming from to write effectively and consistently.

Story Structure #8

The Impact Character

The Second Most Important Character in a Film

Everyone agrees that the Main Character is the most important character in a film. Why? Because through this person, an audience experiences first-hand the emotions and consequences of the narrative surrounding them. But there is another, less understood character that is primarily responsible for influencing growth in the Main Character. This character is known as the Impact Character.

When the Impact Character is steadfast, then he will make his arguments to the Main Character in reference to his own drive. He will treat his own drive as if the same things should be driving all others as well.

This often pops up in conventional arguments where the Impact Character says to the Main Character, "you know, we are just like, you and I," (if the IC is steadfast) or "we are nothing alike," (if the IC changes)."

Is that true? Is it really that black and white? "We're alike" if the Main Character changes and "We're nothing alike" if the Impact Character changes. Is it really that easy?

Overall, we should understand that this is a generality and therefore shouldn't be taken as a strict rule of dramatic narrative, but it started me thinking. How did this generality hold up under further scrutiny? And more importantly, could it help me with my own work?

I took six Impact Characters, three who Change and three who Remain Steadfast, and applied the above concept.

Change Impact Characters.

Score one for Marshall Samuel Gerard. Chasing Richard Kimble (Harrison Ford) in and around Chicago I could hear Tommy Lee Jones uttering "We are nothing alike Richard." Gerard is not the type to suggest that he and a fugitive wanted for murdering his wife are anything alike. It would be quite strange to hear him say so.

Robert the Bruce (Angus MacFayden)...hmmm. "We are nothing alike, William Wallace (Mel Gibson)." Perhaps deep down inside his shameful self might feel that, but I don't recall him ever saying it aloud. Instead the voice of disparity comes from Robert's father, the Leper. Robert wishes to join Wallace but his father reminds him that Robert is a noblemen, not some commoner like Wallace. "Uncompromising men are easy to admire ...But it is exactly the ability to compromise that makes a man noble." As his father puts it, Robert and Wallace are nothing alike.

In October Sky - Coal-mining father John Hickam (Chris Cooper) certainly doesn't feel like he and his son Homer (Jake Gyllenhaal) have anything in common. John considers himself more of a practical man while Homer has head (and his rockets) in the clouds. Again I believe he even has a conversation with his wife about how he and his son are nothing alike.

Steadfast Impact Characters.

And now we move on to Lester Burnham (Kevin Spacey) and his own "personal hero," Ricky Fitts (Wes Bentley). When Ricky's boss threatens to fire him for not working, Ricky tells him, "Fine, don't pay me. I quit. Now leave me alone." Words Lester wishes he could say to his own boss. Ricky doesn't come out and say "You and I are alike," but he might as well have.

What about the obviously named Cole Sear (Haley Joel Osment) and his relationship with the troubled child psychologist Malcom Crowe (Bruce Willis)? In the classic hospital scene, Cole asks "Tell me why you're sad." At first Malcom refuses, but soon realizes that Cole is just as sad as he is; perhaps opening up could help the young boy out. Again, the words aren't said but the intention is there.

And what about Andy Dufresne (Tim Robbins in Shawshank Redemption)? Before he tells Red (Morgan Freeman) about Zihuatanejo he talks about the whirlwind tornado that fate dealt him. "I just didn't expect the storm would last as long as it has." We cut to Red, his head hung low. And although we can't read the expression on his face, we know for certain that Red feels the same. Personally I like it much better when you can do the "You and I are alike" line without actually having to say it - part of the reason why I chose these examples.

So does the rule work?

It seems like it does. I mean, you can't imagine Ricky telling Lester "We're nothing alike" or John Hickam telling his dreamer son "You and I have so much in common. Let's sit down and talk about our dreams." Still, it's probably not a good idea to rely on it all the time, but I do think there's a real world reason for why the rule works so well.

The character who has the most to lose (or gain depending on how you look at the Change) is more often than not the one who will resist any notion of similarity between the other.

When someone tells you, "You know, you're acting just like so-and-so" and you react with disgust or disbelief, chances are that so-and-so is your own personal Impact Character. We hate seeing a part of us that we don't quite understand or even want to accept.

This resistance is a resistance to Change and depending on which side of the argument you stand, you're either going to be a proponent for it or you're going to speak out against it. That's one of the main reasons why the Impact Character exists: to provide that other side of the argument. So it's comforting to know that with a few simple words ("We're both alike" or "We're nothing alike") you can easily tell which side of the argument this second most important character stands on.

Story Structure #9

When the Main Character is Not the Protagonist

One of the most important things you can do to better understand story is to separate the Main Character's storyline from the overall storyline. It's a difficult concept to grasp at first, but once fully understood, helps to create endless possibilities of great storytelling.

So why make a distinction between the two?

When you blend the two together you can cause all kinds of blind spots during the writing process. It's the reason why so many people confuse the Main Character with the Protagonist and assume that both are the same. It's the reason why so many story theorists ascribe to the Hero's Journey mythology made famous by Joseph Campbell. And it's also the reason why some unsuccessful stories can have too many Main Characters. Writers that suffer from the latter haven't taken the time to identify the one personal viewpoint on the story's central problem; they're essentially grasping at story-straws for something that they know they need, but can't quite exactly figure out what.

Separating Hero, Protagonist, and Main Character...

A Main Character is the player through whom the audience experiences the story first hand.

A Protagonist is the prime mover of the plot.

A Hero is a combination of both Main Character and Protagonist.

In other words, a hero is a blended character who does two jobs: move the plot forward and serve as a surrogate for the audience. When we consider all the characters other than a Protagonist who might serve as the audience's position in a story, suddenly the concept of a hero becomes severely limited. It is not wrong, just limited.

So the Main Character is the central character in the Main Character Throughline while the Protagonist is the central character in the Overall Story Throughline. They can, and often are, the same character but they don't necessarily have to be. In fact, there are many stories that don't follow this pattern. To Kill A Mockingbird is the example used in the theory book. Attitcus (Gregory Peck) is the Protagonist in the larger overall storyline surrounding the trial of Tom Robinson. Scout (Mary Badham) is the Main Character in the very personal storyline examining her prejudices towards "Boo" Radley. Both examine prejudice; the former from a more cold, logical perspective, the latter from a more heartfelt, emotional perspective.

More recently I learned that the William H. Macy Las Vegas casino film The Cooler also doesn't follow this usual pattern.

Bernie Lootz (William H. Macy) in 'The Cooler' fulfills the role of the Main Character. As the Shangri-La's resident "cooler," Bernie is a man who can manipulate others through his mood; his very presence can turn a hot craps table into, well, crap. This psychological effect is something that Bernie would take with him into any other story and thus becomes his greatest personal problem. It just so happens that this problem works great in a story about Las Vegas casinos.

The overall story in that film examines the conflict between Old Vegas and New Vegas. The young upstart Larry Sokolov (Ron Livingston) wants to transform the rundown Shangri-La into a major competitor for the newer casinos on the strip like the Bellagio or the Wynn. Standing in his way is Shelly Kaplow (Alec Baldwin), the current manager of the Shangri-La. Shelly represents the old way of doing things and resents any attempts to "Disney-fy" his casino.

So where does Bernie fit into this story and why is he not the Protagonist?

Tips for Identifying the Main Character

There are two techniques I've learned that can be very effective for pulling the Main Character's storyline out of the Overall Storyline. Either one may help you in writing your own story:

* 1. Take the Main Character out of the current story and put him or her in a completely different one. What personal problems would carry over into this new story?

* 2. When writing the Overall Storyline forget your character's names and only refer to them in terms of their roles. In doing this, you'll naturally assume an impersonal objective view of your characters, making it easier to identify how they fit into the Overall Storyline.

Instead of writing Bernie into a story about casinos, what about making him the central character in a story about hiking Mount Everest or pretending to be a secret agent? What would be some of the issues he would take with him into that new story? If he was hiking as part of a larger expedition his mood might make it difficult for others to make it the top of the mountain; some might even quit. In a secret agent story, his mood might be so powerful that his very presence would make some villains reconsider their efforts towards global domination.

The second technique becomes helpful when analyzing films like The Cooler. At first glance it may seem that Bernie is the Protagonist. After all, he is the one we care the most about and his goal of leaving Las Vegas does way heavily throughout the story. But when we look at Bernie in terms of his role as the "cooler," we can see that he has little more than an ancillary effect on the main plot of what to do with the Shangri-La. He is not a prime mover of that plot - the casino manager (Shelly) and the young upstart (Larry) are.

The Cooler - Protagonist and Antagonist Face Off

The question then becomes which one is the Protagonist and which one is the Antagonist-something that would probably be better answered in a separate article. For now, it is enough to say that Shelly is the Protagonist while Larry is the Antagonist. Bernie exists in the story and interacts with both, but he is not a prime mover of the plot. While Shelly and Larry do the bulk-work of the plot in the story, it is Bernie who is our "in" into the story itself; he's the one we identify most personally with.

- Week 5 -

Project #12

Research: Movie Trailer

Find a movie trailer that was edited in such a way that it peaked your interest and gives you a taste of what the story is about but skillfully does not show any spoilers.

Tip: movie-list.com

Homework Assignment: Watch "Memento"

Download and watch Christopher Nolan's film Memento and be prepared to discuss the movie's story structure next week, you can see it here -

Memento (717 MB) (warning: it's a big download, wait till you have a fast internet connection).

Project #13

Storyboard Assignment: Justice League

View this clip.

Download this template:

PSboards.

IN PHOTOSHOP...

Storyboard the sequence, duplicate the panels on mulitple layers, draw over top each one to add in notes, scene numbers and sketch in all the rough poses of all the action, then pass in the Photoshop file to the instructor once complete. Make sure all layers are labeled by page number and are all invisible.

Play and pause on each shot, indicate any camera moves, changes in poses and expressions, recreate the framing and subject placement for every scene. Keep it rough and simple, imagine you are reverse engineering the sequence as you break down these shots to storyboard them. Think about the pacing and editing, why the cuts are framed the way they are, and the main focal point in each shot.

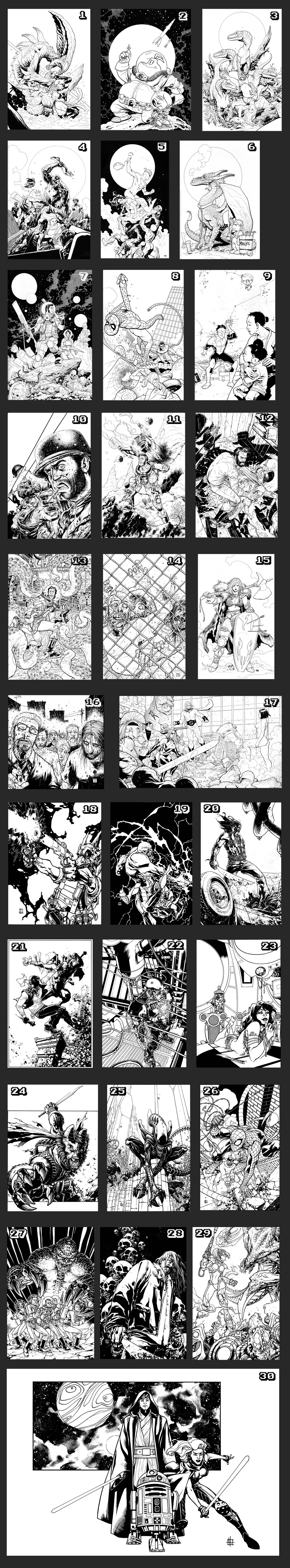

There is much you can learn from studying the many styles of composition practiced by master comic strip artists and illustrators.

Project #14

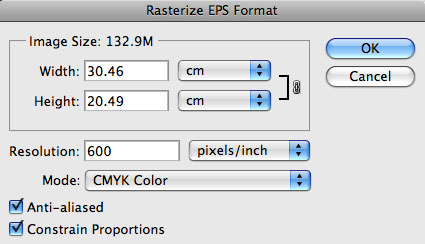

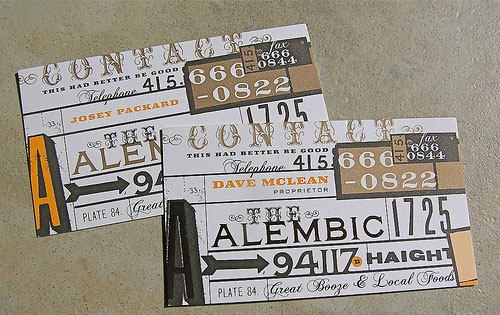

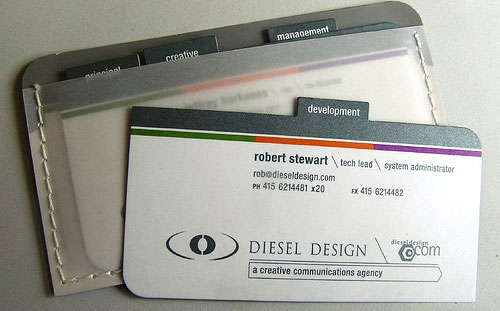

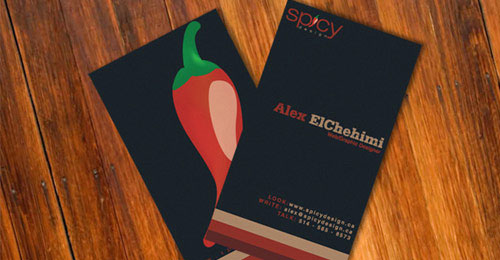

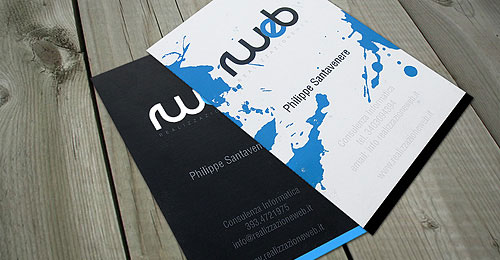

Print-Ready Business Card:

Now to put your Photoshop skills to good use.

With total freedom and creativity, design your own business card!

Business Card Content

The goal of a business card is to make it easy for someone to contact you. Put as much of the following as possible:

Download this pre-formatted template and open it in Photoshop...

Right Click & Save this link:

2" x 3.5" Standard Business Card Template

Verify that you have guides turned on. You should see lines around the outside of your template. If you can't see them: Go to View > Show > Guides to activate them.

The outermost lines are called cut/trim lines. The cut lines show where your design will be cut away from the much larger sheet of paper it was printed on. This ensures that all colors will go to the very edge of your cards. This method is called full bleed.

Your background colors/design MUST extend past the cut lines!

The innermost lines are called the safety lines. Anything outside these lines run the risk of being cut off. Although the cutting machines are very accurate, staying inside of this area ensures that important text/graphics won't be chopped off. It also helps make your card more readable. Keep all your non-background text, logos, pictures, etc. inside of these lines.

Verify that your design is in the proper color mode and size:

Image > Mode > CMYK

Image > Image Size > Width: 3.6", Height: 2.1", Resolution: 350 pixels/inch

Now you are ready to begin designing your business card. It's up to you to decide what you want the card to look like. Start experimenting and sketch out a few layout ideas on paper first to get the look you want. With unlimited amounts of colors and tools to choose from, anything is possible.

Remember to create separate files for each side of your business card (if you wish to have printing on the back). If you want the template to be vertical instead of horizontal - simply go to Image > Image Rotation > 90 degrees CW.

Example of a finished design:

That's it!

The rest is up to you.

Create your own professional business card.

Have fun with it, once completed, save a copy as a JPG file and send it to the instructor.

Some Resources you could use:

- Various Images and Textures

- Paper Textures

- Random Stock Images

- More Background Textures

Something funny:

Some inspiration:

If you ever want to print your business cards and have them mailed to you (50 cards for about $30), you can go here: moo.com

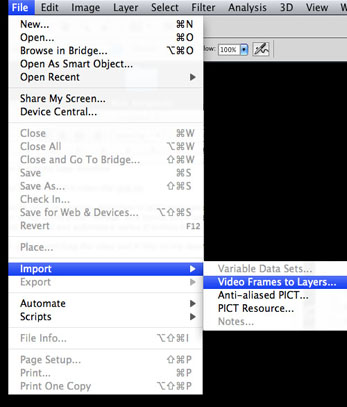

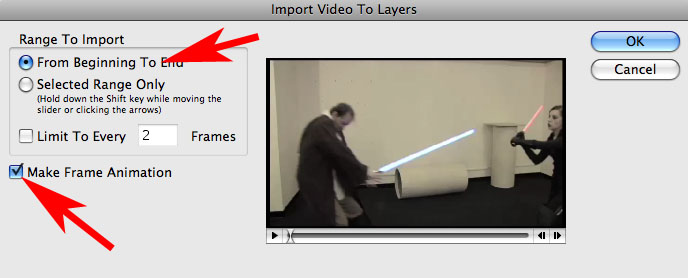

Project #15

Photoshop: Animation/Rotoscoping & Actions Workflow

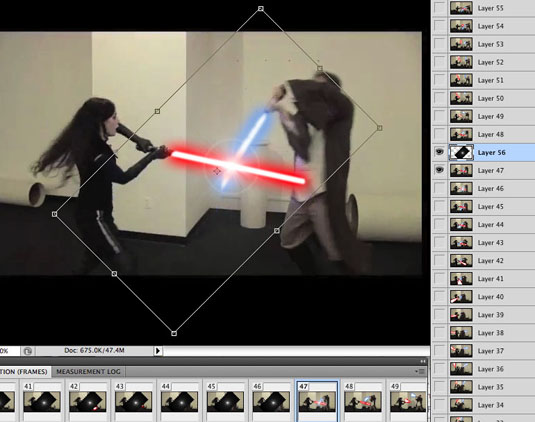

Download and extract this video clip: jedi.zip

'Rotoscoping' is an animation technique in which animators trace over live-action film movement, frame by frame, for use in animated films. In this tutorial you'll be learning about how to add rotoscope-style animation on top of live action digital footage, as a bonus, you'll see how to use the Actions tab to record and play back a series of tasks and commands to use over and over again.

Once the download is complete, unzip the file and drag the video and images on the desktop.

Go to File > Import: Video Frames to Layers...

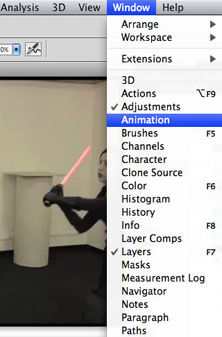

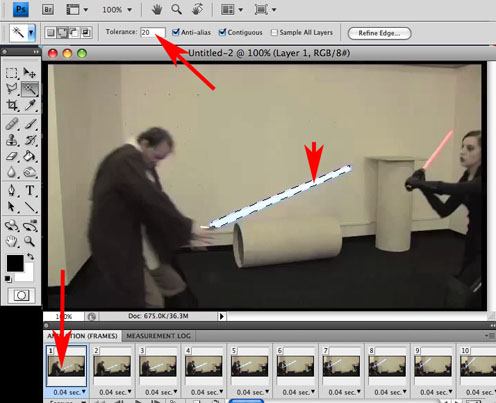

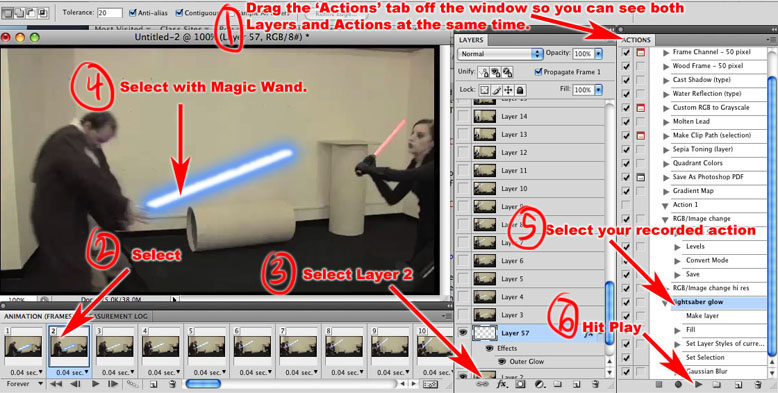

Make sure you have your Layers tab and your Actions tab visible, if you don't see them on the right side of your screen, select the Window menu and click on them. No go to Window > Animation to pop up the animation timeline.

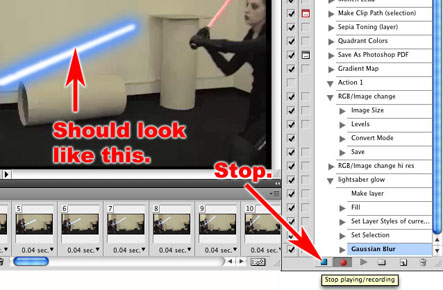

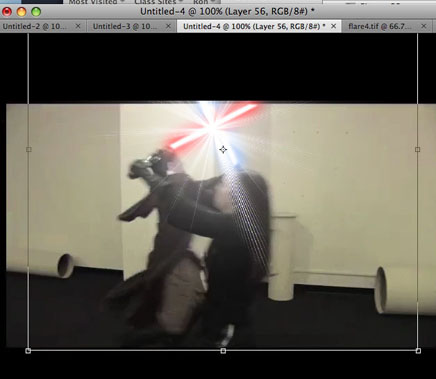

Here you have all 55 frames from this short clip of two people sword fighting. What we'll do is add some more glows to the special effects of their lightsabers.

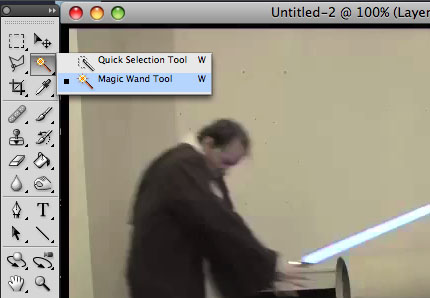

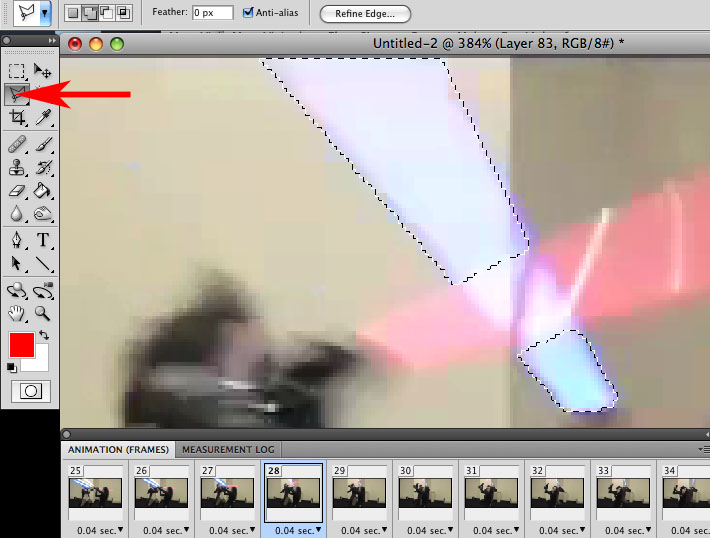

First off, select the Magic Wand tool. We'll start with the guy in the brown robes, make sure you have a threshold of about 20 in your magic wand options bar at the top. Click on the white part of his lightsaber. If it doesn't look like you've got a straight-edge selection of the whole white part of the 'blade' then Edit > Undo and try again.

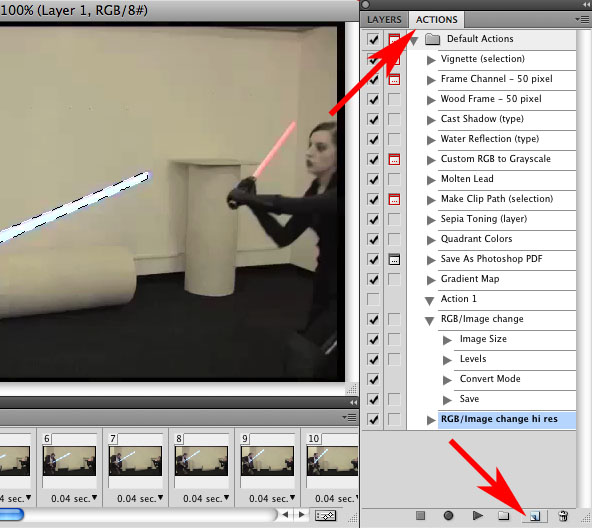

Now we're going to record a new 'Action'.

Photoshop Actions are used to save time and make you more productive during post-processing. They can be used to speed up repetitive tasks, make quick work of time consuming edits, and give you a little creative inspiration. Whenever you perform a repetitive task in Photoshop, you can save yourself time and effort by using Actions.

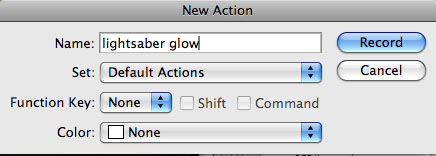

With the lightsaber still selected, go to the Actions tab and click on the 'create new action' button. Name the new action "lightsaber glow" and hit the record button. Now every operation you do in Photoshop will be recorded.

Go back to your Layers tab, create a New Layer. With your lightsaber still selected, go to Edit > Fill: pick White for your color, hit OK.

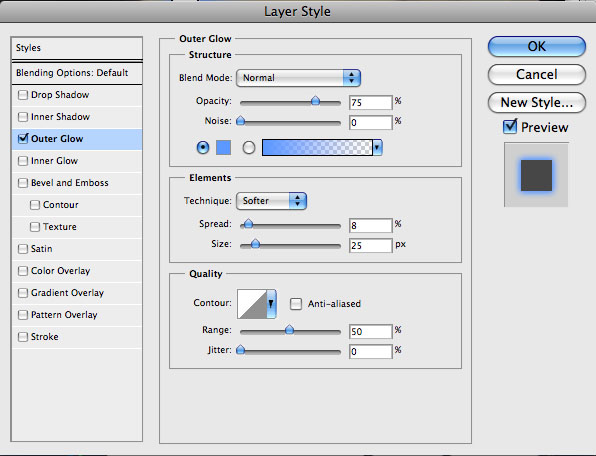

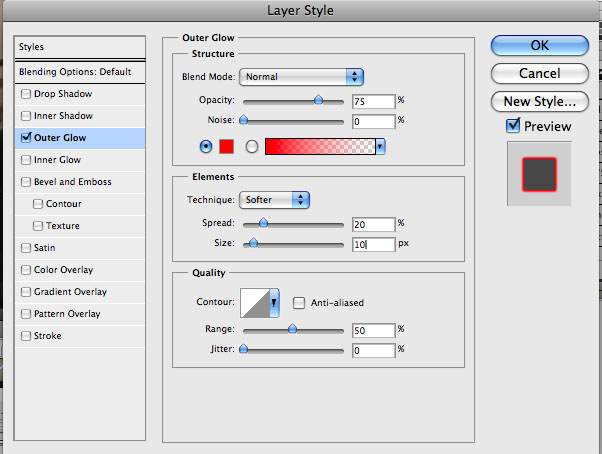

Double click on that layer to bring up your Layer Style.

Pick the Outer Glow Blending Option and pick these options.

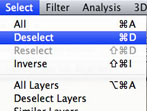

Now go to Select > Deselect.

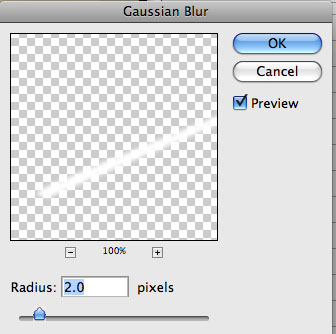

Go to Filter > Blur > Gaussian Blur ...choose a Radius of 2.

Go to Layer > Merge Down.

This will make the edges even more fuzzy to blend in the white core

and the colored glow and combine your FX layer with the frame's image.

Go back to your Actions tab and hit the stop button.

You'll notice that you have the lightsaber effect on your animation timeline.

Now to easily repeat the process. Go to frame 2 on the timeline then select the next layer up (Layer 2).

Choose your Magic Wand, click on the new lightsaber blade again. The go to your Actions tab > select "lightsaber glow" and hit the Play button.

Instantly the glow should appear on your second layer/frame. Repeat the process, select Frame 3 and then Layer 3.

Select the lightsaber with the Magic Wand, hit Play on the Action.

Now keep going, scrolling right on your timeline and moving up the list of layers... repeat the process for all 55 frames and layers.

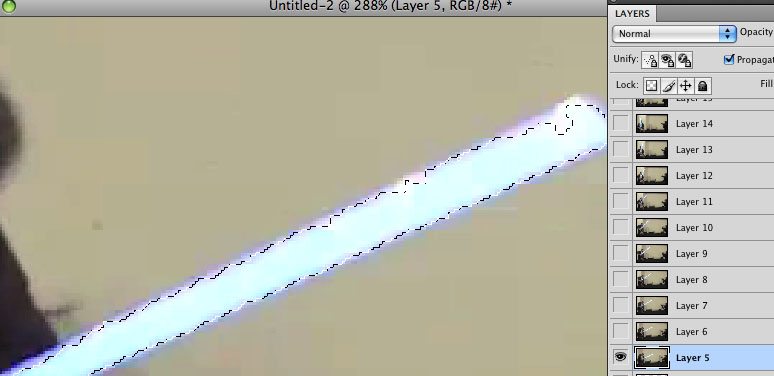

You might come across some sections where the Magic Wand doesn't select the whole lightsaber, simply hold the Shift key and click the gaps to add to the selection.

This is where it can get tedious, repeat this process over and over again. If at some point you don't like how the glow turned out, maybe it's not smooth enough, just hit Alt+Ctrl+Z mulitple times to undo the last few steps, and try to make a better selection with the Wand.

You will get sections that might be difficult to select or you need to place the FX behind the other lightsaber, in these cases, zoom in and use the Polygonal Lasso Tool and click and drag around the area of the blade and double click to close the selection, then hold down the SHIFT key to add on to the selection (You can even remove parts be holding down ALT). Once your custom selection is made, hit the Play button as usual.

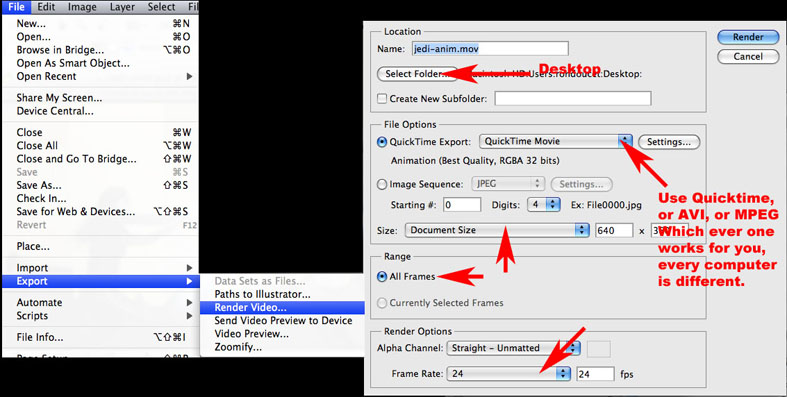

To see the video go to File > Export > Render Video.

In the Location at the top change the folder to your Desktop.

File Options: Quicktime Movie or AVI is preferred,

but test it out and see which looks better.

At the bottom make sure the Render Options > Frame Rate is: 24

It instantly renders the video, now you can play it off the desktop.

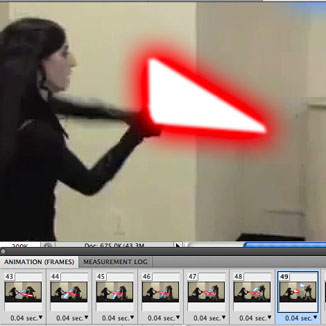

Once you're done it should look like this.

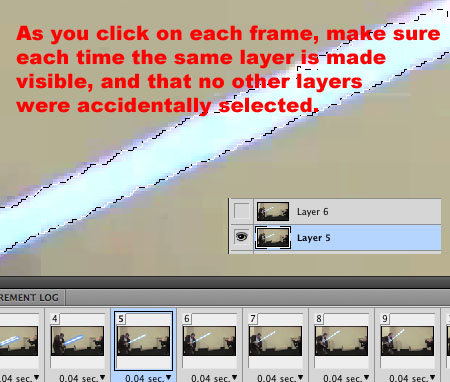

If you find there's some frames playing out of sync then all it means is that the order of your frames have been changed from the order of your layers, this is an easy fix.

Click on the first frame on your timeline in the Animation tab. Keep clicking each frame one at a time, frame 2, 3, 4 etc. each time look to see which layer in your Layers tab is being visible with the tiny eye icon. When you reach a layer that does not match the same number as your frame, simply correct it by clicking the eye on the right layer (to match the frame number), and that's it.

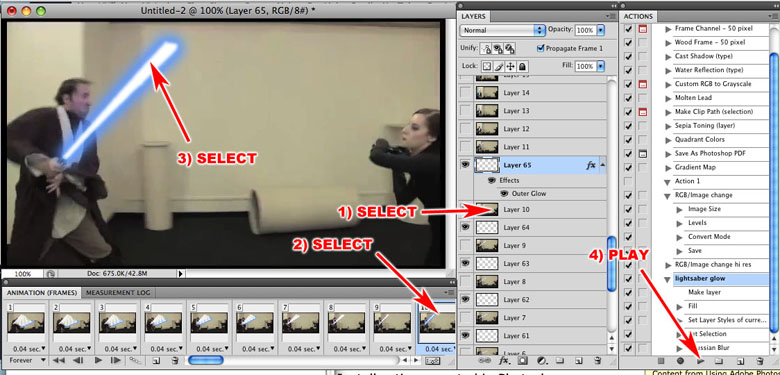

Now repeat the whole process for the red lightsaber.

Go to the first frame in the Animation tab, select it and select the first layer in the Layers tab. Select her red lightsaber with the Magic Wand. Go to the Actions tab and click on the 'create new action' button. Name the new action "red lightsaber" and hit the record button.

Go back to your Layers tab, create a New Layer. With your lightsaber still selected, go to Edit > Fill: pick White for your color, hit OK. Double click on that layer to bring up your Layer Style.

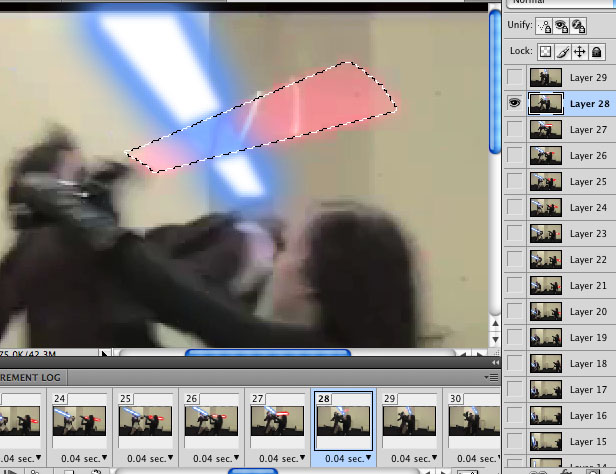

Pick the Outer Glow Blending Option and pick these options.

Now go to Select > Deselect.

Go to Filter > Blur > Gaussian Blur ...choose a Radius of 1.

Go to Layer > Merge Down.

This will make the edges even more fuzzy to blend in the white core

and the colored glow and combine your FX layer with the frame's image.

Go back to your Actions tab and hit the stop button.

You'll notice that you have the new lightsaber effect on your animation timeline.

Now to easily repeat the process. Go to frame 2 on the animation timeline then select the next layer up (Layer 2).

Choose your Magic Wand, click on the lightsaber, go to your Actions tab > select "red lightsaber" and hit the Play button. Repeat the process, over and over. I found that her red lightsaber was sometimes more difficult to select so you might find your self using the Polygonal Lasso tool to just click and drag a shape around the blade instead.

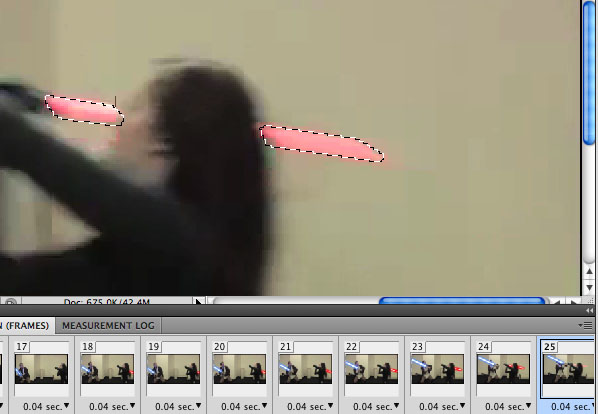

For sections like frame 25 and 28, you will have to use the Polygonal Lasso tool since the blades are intersecting or a body part overlaps it. Also, watch out for all those motion blurs, in those cases use the Polygonal Lasso tool for those ones too to get that stretched out blade image in there for the motion-blur.

Here's the last frame and you're all set.

Render the clip: File > Export > Render Video.

Use the same settings.

Don't worry, we're almost done, let's add in some flares for when the blades hit!

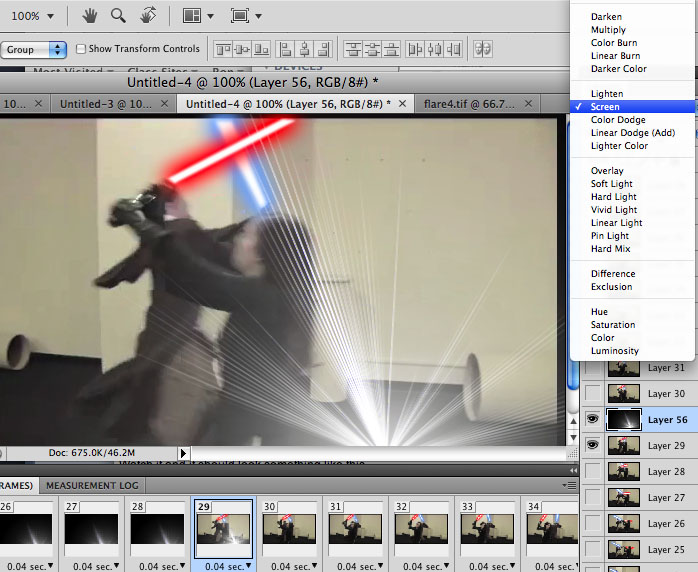

File > Open "flare4.tif" from the pack you downloaded earlier.

Ctrl+A and Ctrl+C to copy it, go back to your work file and Ctrl+V to paste.

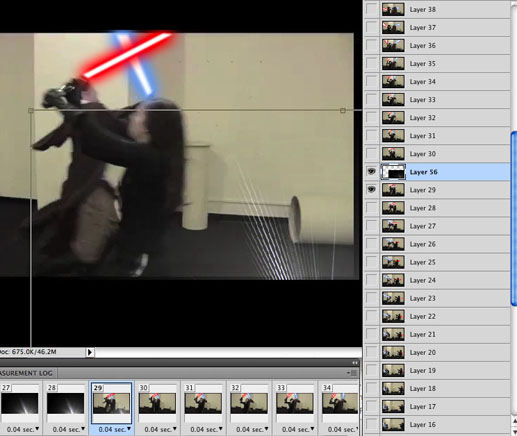

Now click on that new layer which was just created with the flare on it, and drag just above Layer 29.

Set the layer to Screen Mode to make the black invisible.

Press Ctrl+T and move the around the flare until you see the outer edge so you can hold down Shift (to maintain proportions) and click and drag to shrink its size down. Remember - hold down the spacebar and click and drag to move around the canvas.

Now reposition it and double click on the flare itself.

Go to Filter > Blur > Gaussian Blur... Radius: 3

Hit OK.

Make sure to move the flare right where the blades intersect.

Go to Layer > Merge Down.

Now select Frame 46 and select Layer 46.

Open "flare1.tif"

Ctrl+A and Ctrl+C to copy it, go back to your work file and Ctrl+V to paste.

Set the layer to Screen Mode.

Press Ctrl+T and move the around the flare until you see the outer edge so You can hold down Shift and click and drag to shrink it's size.

Make sure to move the flare right where the blades intersect.

Now press Ctrl+A and Ctrl+C to copy this small flare (we'll be using this for the next frame).

Go to Layer > Merge Down.

Select the next Frame (47) and the next layer up (Layer 47).

Crtl+V to add the small flare back in.

Set the layer to Screen Mode.

This time scale it down and rotate it (Ctrl+T).

Go to Layer > Merge Down.

This creates a simple 2-frame animation of the flare bursting out and shrinking.

Repeat the process for the very last frame too.

Go to File > Export > Render Video...

Click OK.

You're all set to watch your video.

If you find the flash flares too weak simply go to the proper frame (and layer) and press Ctrl+V, set the layer to Screen Mode. Position the flare, merge the layer down, and re-render the video.

In the end it should look like this.

Now go out and film you and your fellow geek-friends playing with some sticks, knowing you can turn yourselves into lightsaber-wielding Jedi!

Bonus: Learn more about how to edit multiple images with a single action using batch processing to make the same adjustments to hundreds of photos in this tutorial.

Story Structure #10

Consistent Plot Points

In a story, the major plot points are either driven by decisions or actions. While a story may naturally ebb and flow between both, when all is said and done, one of these will be seen as the primary driving plot force in a story. This is because meaningful stories are really just an argument and effective arguments have a pattern they must adhere to.

An author picks either an action or a decision to set the wheels of inequity into motion. In doing so, the argument of the story is begun. Choosing whether an action leads to a decision or a decision leads to an action is essentially telling an audience "This sort of thing leads to that." This pattern is now set up as the pattern of logic that will be examined in the Objective Story. An author then concludes her argument with the meaningful bookend, "No. Actually, this sort of thing leads to that."

Meaningful stories are really just an argument.

This is a simplified look at the mechanics in a story, but is essential towards understanding why the story driver must stay consistent.

If the major plots are different or are changed halfway through a film, the integrity of a story falls apart. The author ends up making an argument that sounds something like this: "This sort of thing leads to that. Well...no. Actually, that sort of thing leads to this."

The author who does this has, in essence, begun a completely new argument. The context has been spun around on an unsuspecting audience.

We, as an audience, were originally examining the logical effects of decisions leading to actions, or actions leading to decisions. This was the pattern that was being appraised. If we were looking at why certain decisions lead to problematic actions, we'd like to know what kinds of decisions would lead us away from those problems (or towards more if the overall story ended in failure). Likewise with actions leading to problematic decisions.

The fantastic thing about knowing the plot driver of your story is that you never again have to suffer from that awful question, "What happens next?" An action-driven story requires an action to spin the story in a different direction. A decision will do nothing to further the story. The same with decision-driven stories. In order for a decision-driven story to progress the story requires a decision to be made. Trying to force an act-turn with an action simply won't work.

Star Wars was driven by actions (Death Star created, Death Star destroyed), while The Godfather was driven by decisions (Don Corleone decides not to support the drug running, Michael decides to become the new Godfather). Toy Story was driven by actions (Buzz arrives in Andy's room, Buzz and Woody "land" in Andy's car), while Searching for Bobby Fisher was driven by decisions (Josh decides to hold on to the chess piece instead of the baseball, Josh decides to offer a draw to Jonathan).

Countless other great films stay consistent in the type of plot point that drives their story forward. At the very least, the two most important plot points - the Inciting Incident and the Concluding Event - need to be either both based on actions, or based on decisions.

Story Structure #11

Personal Tragedy

Feeling good about losing out is one thing, feeling miserable about winning is something else. Like the personal triumph, the personal tragedy straddles the emotional bridge between an all out rejoicing and an overwhelming depression.

But whereas the former emphasizes the good, this kind of ending focuses on the bad. It's the bitter half of a bittersweet ending, an ending that far too many of us have experienced in our own lives.

Success often comes with a price.

That's the overriding message of this kind of ending. These stories focus on the internal turmoil a Main Character suffers through in their endeavors to achieve success in the story as a whole. Often the Main Characters in these stories have pushed themselves to such an extreme that they have forgotten or buried their own personal issues. Victory, it would seem, is no salvation for one's personal demons.

The following clips are examples of stories where the good guys win, yet the Main Character goes home sad:

Besides being great films, what each of these clips have in common is an overwhelmingly gloomy soundtrack. In fact, they're so similar that they almost become interchangeable. Dark and ominous minor chords support what should otherwise be a joyous occasion. The Joker's vile scheme to plunge Gotham into chaos has been thwarted. Shouldn't Batman and Commissioner Gordon be jumping up and down with joy like mad? After all, in addition to stopping the Joker, they did manage to thwart Two-Face's attempt at dastardly revenge. Where's the all-out celebration? As it turns out, this downer is all Bruce's fault.

Throughout the The Dark Knight, Bruce Wayne (Christian Bale) has struggled with the impact he has had on the public and whether or not his presence is a good thing or a bad thing for the people of Gotham. He wants to be the hero, but realizes in the end that the only way he can save them all is by becoming the bad guy. He assumes responsibility for Harvey's murders and tells Gordon to let loose the dogs. In doing so, he secures Gotham's future, but at the price of his own. The good guys win, yet the Main Character goes home sad (or better yet, unfulfilled).

The Batman has seen himself live long enough to become the villain.

Personal Tragedy in Story Structure.

Bruce Wayne/Batman begins the film tormented with the kind of influence he has had on Gotham. Is he a force for Good or is he instead a catalyst for Evil? He spends the entire film mulling over his role as the Batman, desperately trying to find someway out or someone to replace him. In the end, he takes Two-Face's place as the villain - someone the people of Gotham can hunt and chase down. As the closing narration tell us, he becomes the Dark Knight.

In that film, Bruce Wayne has failed to resolve his angst. No smile there. He's still stricken by the fact that he has this negative influence on the city of Gotham. That's the very definition of a personal tragedy - a Main Character still stuck with the issues that they began the story with.

In The Wrestler...

When I saw the film the first time, I was trying to determine exactly what the writer or filmmaker was trying to communicate, it's never an easy process. I assumed this was more of triumph film than a tragedy, he had gone through personal growth his character didn't change from start to end, he went through lots of personal thinking and emotional ups an downs, in the end he realizes and accepts who he is and goes down the path he is most happy with, even though it may not be the right one.

But the film certainly has a bittersweet quality that most triumphant films lack. And when you take a step back and look at the film as a whole, it does appear that what they were trying to depict was a character who was willing to sacrifice it all for the roar of the crowd. It sounds more sophisticated and is probably closer to the kind of meaningful ending that Darren Aronofsky was going for.

Once I saw the film the second time, I saw it for what it truly was, a personal tragedy film. After his speech, and just before he makes the decision to kill himself for the crowd, Randy looks to the wings where his worst fears have been realized. The woman he loves has abandoned him, repeating the rejection by his daughter. He reverts back to his standard, lonely life and steels himself for what he will do for those who care more for The Wrestler, than Randy himself.

Story Structure #12

Personal Triumph

Sure, there are times when I succeed in my goals and feel really great about it. Likewise, there are moments when I fail in my efforts and feel really miserable about it (unfortunately more the latter, than the former). But rarely does life ever work out this nicely. More frequently, I find that I achieve my goals at the expense of my own personal life or I find that failing miserably turned out to be the best thing for me. Either way, it seems these outcomes happen more often than all-out triumphs or tragedies.

The only drawback with identifying these kinds of stories is that there isn't a great one-word term to explain them like there is with triumphs or tragedies. In a general sense they can be called "bittersweet," but even this isn't as accurate as it should be. Which is more prevalent, the bitter or the sweet? And to what part of the story does it apply? Bittersweet accurately describes the general feeling these kinds of stories have, but it's not too helpful in the actual creation of a story.

Because the Main Character is such an integral part of a story's meaning it can sometimes be helpful to use their emotional state as a kind of benchmark by which to evaluate the ending of a story. With this in mind, the "Bittersweet" ending can be divided into two categories: the Personal Triumph story and the Personal Tragedy story. The second (my ultimate favorite) will be looked at in greater depth in the following article, but for now, I'd like to focus on the sweeter part of bittersweet.

Developing The Personal Triumph.

These are the stories where the good guys lose, yet the Main Character goes home happy. As always, I've tried to put together a collection of clips illustrating this concept:

The first clip comes from the popular film, The Devil Wears Prada. In this story, Andy Sachs (Anne Hathaway) is the "good guy" trying to succeed in her attempts to be the assistant to Miranda Priestley (Meryl Streep). As the clip above shows though, things don't quite work out the way Andy thought they would.

Having grown to a point where she can confidently make the decision her heart wants her to, Andy turns away and chooses a life of tweed over one of Prada. However, even though she blew it, she still ends up gaining Miranda's approval. The good guy (or in this case gal) loses, yet goes home happy - a perfect example of a Personal Triumph story.

A perfect example of a Personal Triumph story is when the good guy loses, yet goes home happy. In Donnie Darko, the same kind of ending exists.

Just moments before he is crushed by the jet engine, Donnie starts laughing hysterically. Why? Because he is no longer worried about dying alone. Although we don't see the actual act, it's safe to assume that his relationship with Gretchen has grown to a point where he doesn't feel like he's alone in the world anymore (i.e, they slept together). Donnie has love. The Main Character, who started out in a catatonic state, ends up going home happy.

But where does this leave the rest of the world?

Unfortunately, Donnie's acceptance of his own death reverts the Primary Universe back to its miserable state. The alienation and the fixed conservative attitudes, which are the real source of the problems in the story.

Gretchen asks Donnie, "Wouldn't it be great if we could go back in time and erase all that pain and suffering?" But even a time-travelling superhero like Donnie can't outrun the past. Whatever happened, will always be.

Donnie could have let this world end by refusing to go back in time. In doing so, he would have brought an end to all of the painful and incompatible attitudes and the good guys would have won. But he didn't. He found a connection that he never thought he would and felt that that was enough of a life.

The Main Character goes home happy, yet the world as a whole, the "good guys" that we are rooting for, end up losing.

In the film Rain Man - In case it's been awhile since you've seen the film, Charlie Babbitt (Tom Cruise) abducts his brother Raymond (Dustin Hoffman) in hopes that he can ransom him for an inheritance. Along the way Charlie grows to love his brother and ultimately, decides to give up the inheritance. His brother means more to him now than any amount of money ever could. The "good guy" loses, yet goes home happy.

Much simpler to explain than Donnie Darko, but no less meaningful.

It's all about: Feeling Good About Losing Out.

In short, that's what these stories mean and why they feel the way they do. The audiences feels good about losing. In giving audiences something closer resembling real life, these films become cherished experiences that outlast the usual mindless drivel found in most theaters.

- Week 6 -

Project #16

Storyboard Test: Duncan's Revenge

Using the script provided in class and character designs for reference, storyboard the short story in full. Keep in mind of how the types of shots you use will help to tell the story. Write out the dialogue and action desicriptions under each panel.

Download Reference:

Ron's Storyboard Cheatsheet v1.0

Check out this short sequence by Megan Nicole,

Straightforward and effective body language and expressions,

with simple shot compositions that help to tell the story.

Watch Sherm Cohen's Awesome Storyboard Tutorials:

Download these boards.

Project #17

Photoshop: Pixel Art

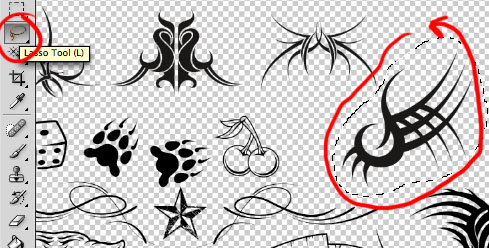

One of the nice things about pixel art is that you don't really need any fancy tools - your computer's built-in paint program is probably good enough! That said, there are programs made specifically for pixel pushing, like Pro Motion, or for Mac users, Pixen. Can't say I've actually tried them, but I've heard good things, Pixen can even do b-bit style pixel animation. For this tutorial, we're going to use Photoshop.

Using Photoshop for Pixel Art

When using Photoshop, your main weapon is going to be the pencil tool (shortcut "B"), which is the alternate for the brush tool. The pencil lets you color individual pixels, without any anti-aliasing.![]() (shortcut "M") and the magic wand

(shortcut "M") and the magic wand  (shortcut "W") for selecting and dragging or copying and pasting. Remember that by holding "Shift" or "Alt" while you make your selection you can add or subtract from your current selection. This comes in handy when trying to grab areas that aren't perfectly square.

(shortcut "W") for selecting and dragging or copying and pasting. Remember that by holding "Shift" or "Alt" while you make your selection you can add or subtract from your current selection. This comes in handy when trying to grab areas that aren't perfectly square.![]() (shortcut "I") to grab colors. Color conservation is important in pixel art for a number of reasons, so you will want to grab the same colors and reuse them.

(shortcut "I") to grab colors. Color conservation is important in pixel art for a number of reasons, so you will want to grab the same colors and reuse them.Straight Lines

Curved Lines

In computer graphics, a sprite is a two-dimensional (or three-dimensional) image or animation that is integrated into a larger scene.

The first thing you need is a good idea! Try to visualize what you want to pixelize, either in your head or on paper. A little work in the pre-planning department can let you concentrate on the actual pixelling later on.

Things to Think About

Let's Wrassle!

Two Approaches

Step 1: Crude Outline

![]()

![]()

In this case, I'm basing my outline almost entirely on my sketch.

First, crank up the zoom to around 6x or 8x magnification so that we can see each pixel clearly. Then clean up that outline! In particular, you want to trim away stray pixels (the outline should only be one pixel thick all the way through), get rid of any jaggies, and add any small details that were passed over in Step 1.

Keep your outline simple. The details will emerge later on, but for now, concentrate on defining the "big pieces", like muscle segmentation, for instance. It may not look like much now, but be patient.

With the outline done, we have a coloring book of sorts that we can fill in. Paint buckets and other fill tools will make it even easier for us. Picking colors can be a little more difficult, however, and color theory is a topic that is beyond the scope of the tutorial. However, here are a few basic concepts that are good to know.

HSB stands for (H)ue, (S)aturation, and (B)rightness. It's one of a number of computer color models (i.e. numerical representations of color). Other examples are RGB and CMYK, which you have probably heard of. Most paint programs use HSB for color-picking, so let's break it down:

Hue - What you understand "color" to be. You know, like "red", "orange", "blue", etc.

Saturation - How intense the color is, or how intense the color is. 100% saturation gives you the brightest color, and as saturation decreases, the color becomes more gray.

Brightness (or "luminosity") - Lightness of a color. 0% brightness is black.

What colors you choose is ultimately up to you, but here are a few things to keep in mind:

1. Less saturated and less bright colors tend to look more "earthy" and less cartoony.

2. Think about the color wheel - the further away two colors are from one another, the more they will separate. On the other hand, colors like red and orange, which have close proximity on the color wheel, look good together.

3. The more colors you use, the more distracted your sprite will look. To make a sprite stand out, use only two or three main colors. (Think about what just red and brown did for Super Mario back in the day!)

The actual application of color is pretty easy. You want to first select the area you're going to fill with the magic wand  (shortcut "W") and then fill by pressing "G" for the paint bucket and switch between your foreground color and background color with "X".

(shortcut "W") and then fill by pressing "G" for the paint bucket and switch between your foreground color and background color with "X".

First, we have to pick a light source. If your sprite is part of a larger scene, there might be all kinds of local light sources (like lamps, fire, lamps on fire, etc.) shining on it. These can mix in very complex ways on the sprite. For most cases, however, picking a distant light source (like the sun) is a better idea. For games especially, you will want to create a sprite that is as generally lit as possible so that it can be used anywhere.

I usually choose a distant light source that is somewhere above the sprite and slightly in front of it, so that anything that is on top or in front is well-lit and the rest is shaded. This lighting looks the most natural for a sprite.

Once we have defined a light source, we start shading areas that are farthest from the light source with a darker color. Our "up and to the front" lighting model dictates that the undersides of the head, the arms, the legs, etc., should be shaded.

Remember that the play between light and shadow defines things that are not flat. Crumple up a piece of white paper into a ball and then unroll it and lay it on a table - how can you tell that it's not flat anymore? It's because you can see the little shadows around the crinkles. Use shading to bring out the folds in clothing, and to define musculature, hair, fur, cracks, etc.

A second shade, lighter than the first, should be used for soft shadows. These are areas that are indirectly lit. It can also be used to transition from the dark to the light, especially on curved surfaces.

Places that are being hit directly by the light source can have highlights applied onto them. Highlights should be used in moderation (much less than shadows), because they are distracting.

Always apply highlights after shadows, and you will save yourself some headache. Without the shadows already in place, you will be inclined to make the highlights too large.

Shading is where most beginners get tripped up. Here are some rules you should always follow when shading:

1. Don't use gradients. The ultimate newb shading mistake. Gradients look dreadful, and don't even begin to approximate the way light really plays off a surface.

2. Don't use "pillow-shading". Pillow shading is when one shades from the outline inward. It's called "pillow-shading" because it looks pillowy and undefined.

3. Don't use too many shades. It's easy to think that "more colors equals more realistic". In the real world, however, we tend to see things in big patches of light and dark - our brains filter out everything in between. Use at most two shades of dark (dark and really dark), and two shades of light (light and really light) on top of your foundation color.

4. Don't use colors that are too similar. There's no reason to use two colors that are very similar to one another. Unless you want really blurry-looking sprites!

Color conservation is something that pixel artists have to worry about a lot. One way to get more shades without using more colors is to use a technique called "dithering". Similar to "cross-hatching" or "stippling" in the traditional art world, you take two colors and interlace them to get, for all intents and purposes, an average of the two colors.Here's a simple example of using two colors to create four different shades using dithering:

Compare the top picture, which was made using the Photoshop gradient tool, and the bottom, which was created with just three colors using dithering. Notice the different patterns that were used to create the intermediary colors. Try experimenting with different patterns to create new textures.

Dithering can give your sprite that nice retro feel, since a lot of old video games relied heavily on dithering to get the most out of their limited palettes (look to the Sega Genesis for lots of examples of dithering). It's not something that I use very often, but for learning's sake, here it is applied (possibly over-applied) to our sprite.