SEND ALL FINAL IMAGES & VIDEOS TO: ron.doucet@gmail.com

With your Name and Project Number in the file name:

"your_name_ project#.JPG"

ie: joe_blow_project03.jpg

PROJECTS = Assignments ranging from various Research tasks, Photoshop tutorials, and Storyboard tests.

STORY STRUCTURE = Reading materials on theory for character development, screenwriting, and plot analysis for film.

IPUB Course Outline

The dates below are the Deadlines for each group of tasks.

You may click on the project name to jump directly to the instructions:

< Week 1 - Due: Apr.12 >

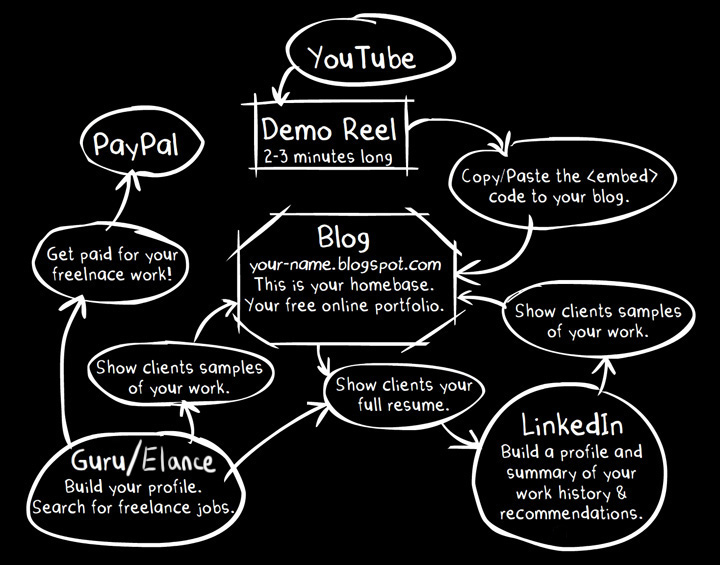

Project #1 - Internet Publishing: Online Portfolio

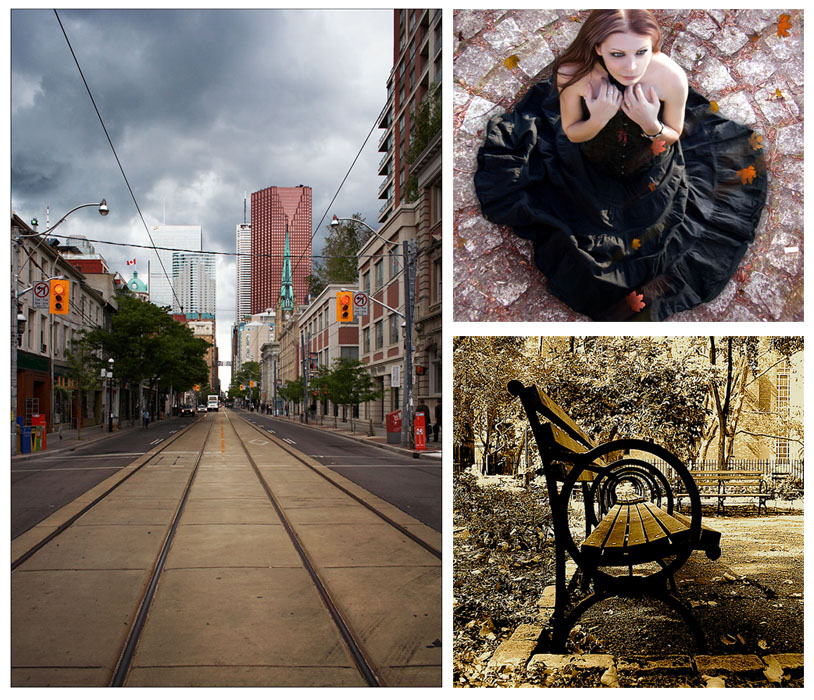

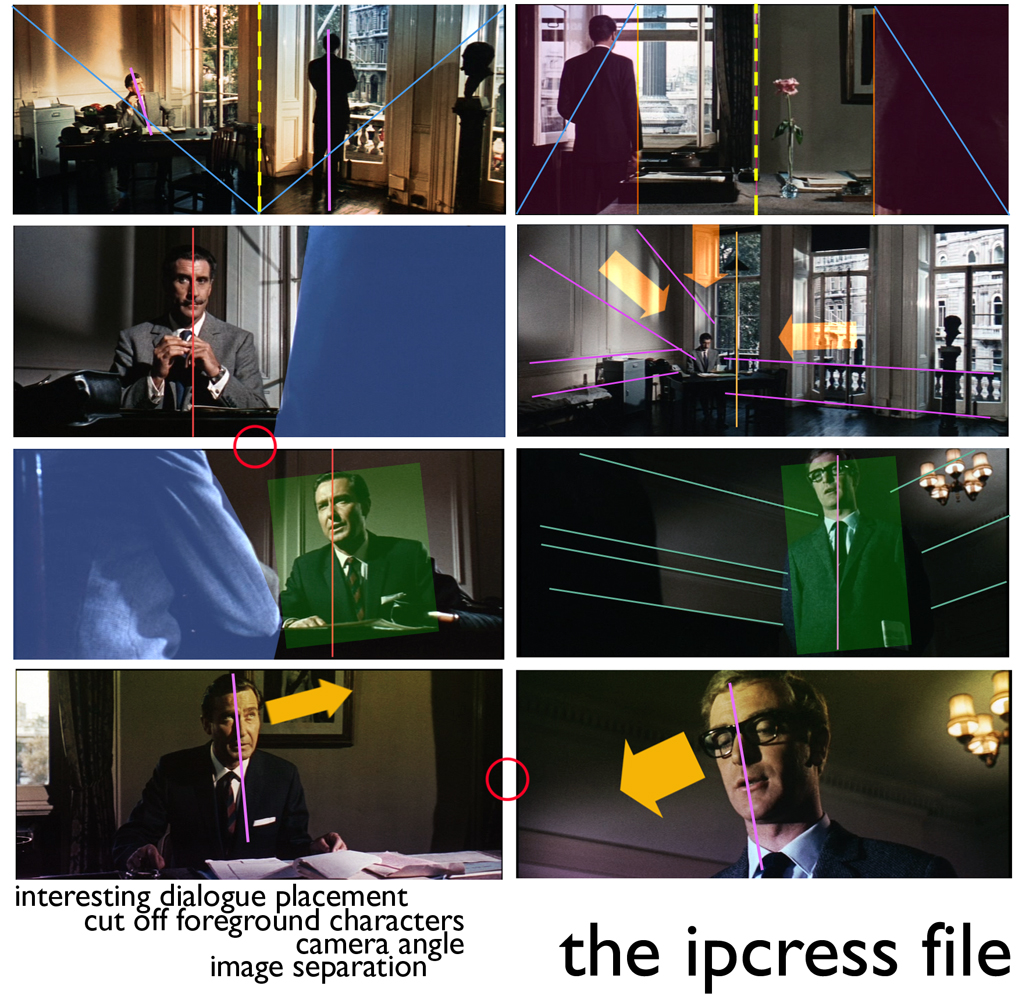

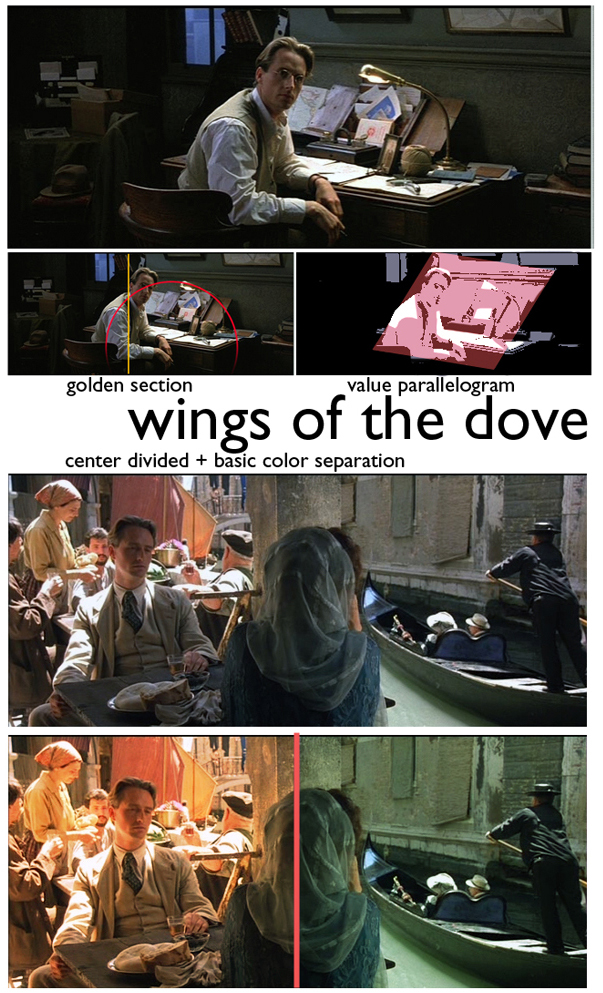

Project #2 - Research: Strong Compositional Style

Story Structure #1: Visual Storyforming

Story Structure #2: Determining The Mind of a Main Character

< Week 2 - Due: Apr.19 >

Project #3 - Research: Triangular Composition

Project #4 - Storyboard Assignment: Leon

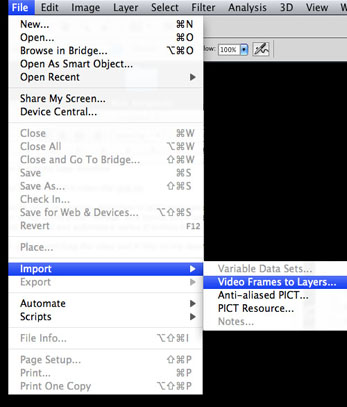

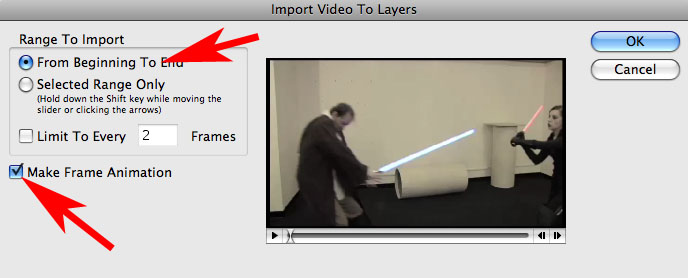

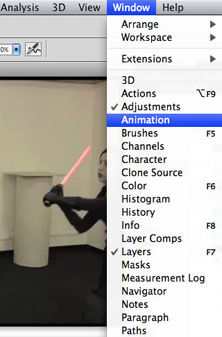

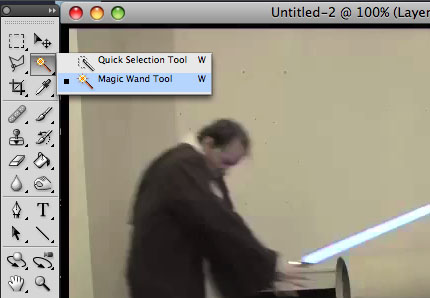

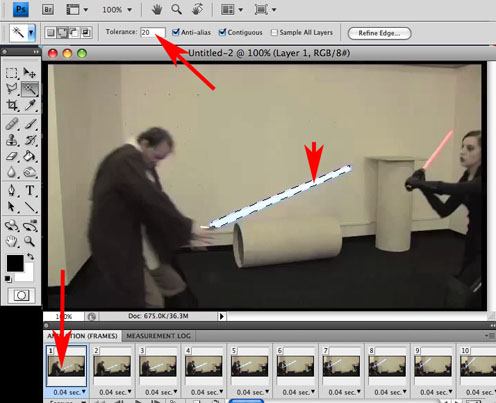

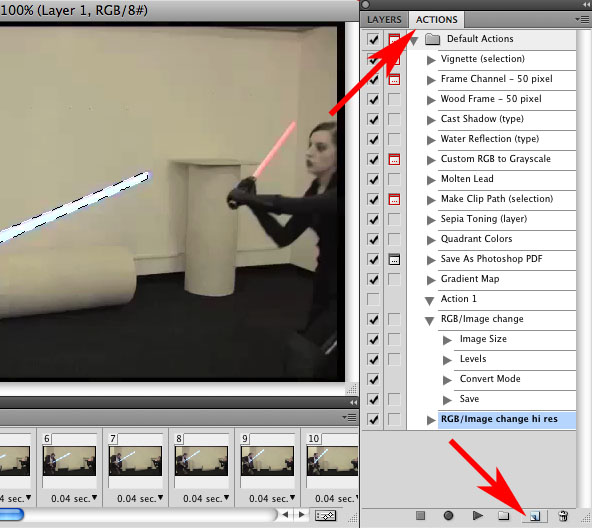

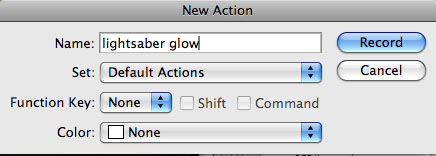

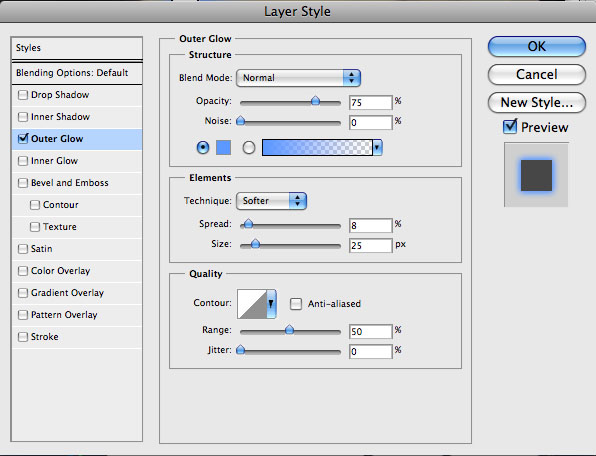

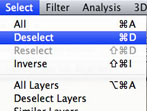

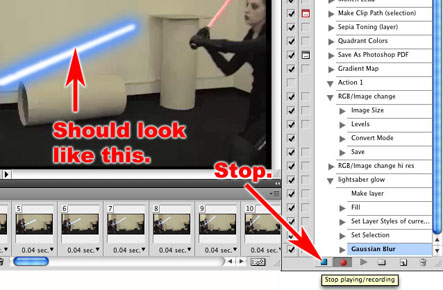

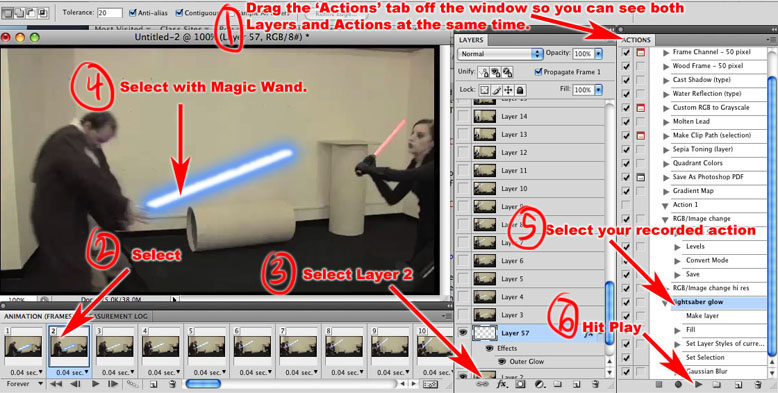

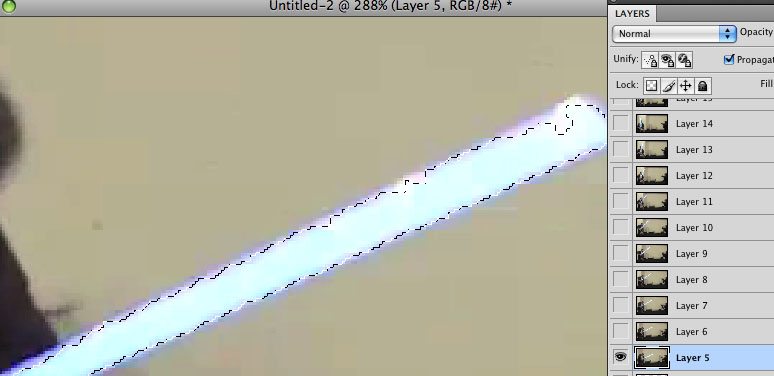

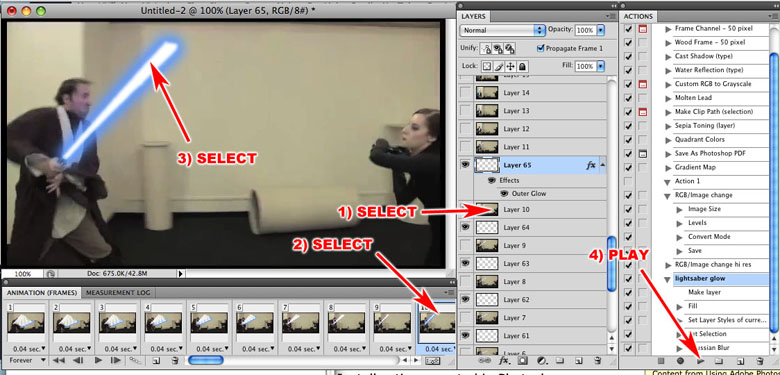

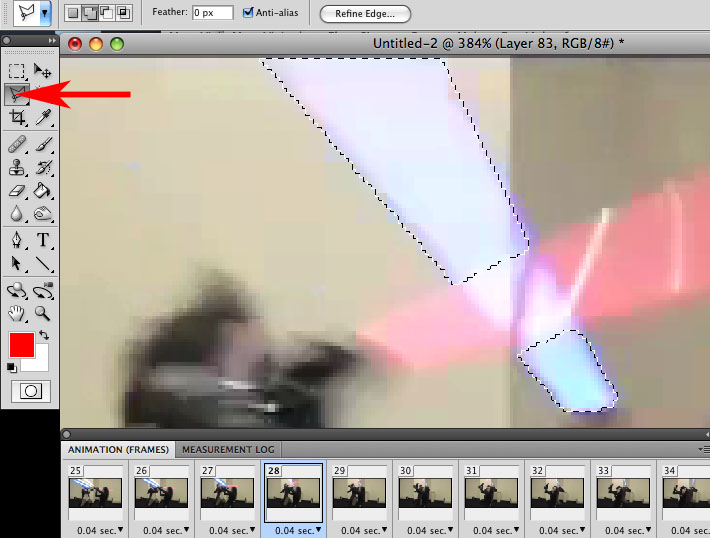

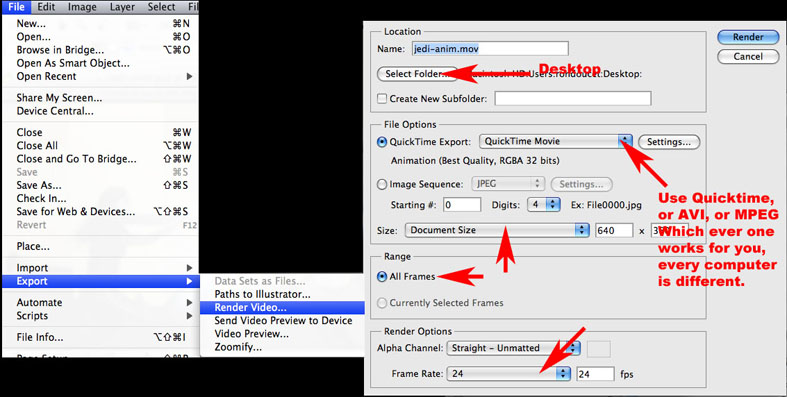

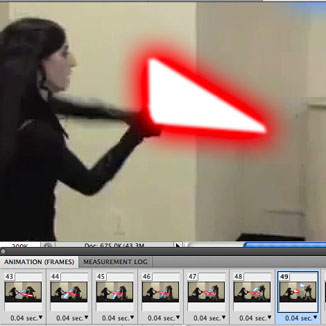

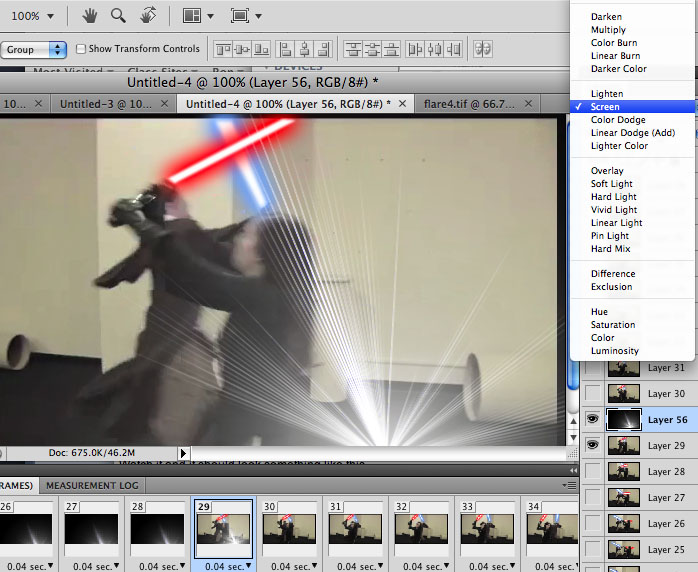

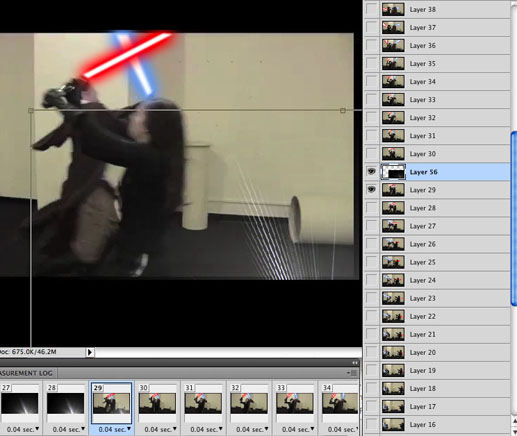

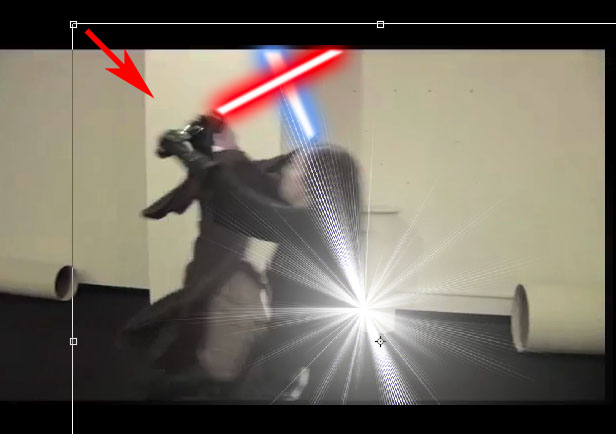

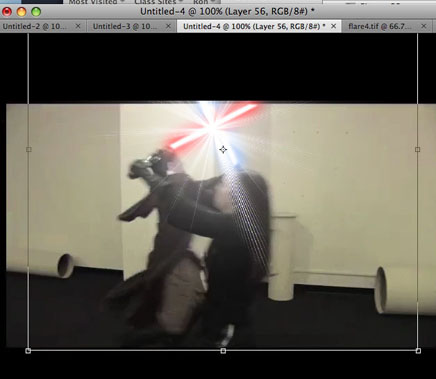

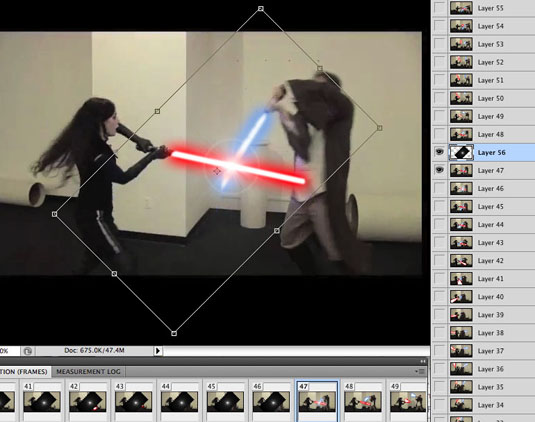

Project #5 - Photoshop: Animation/Rotoscoping & Actions Workflow

Story Structure #3: What Character Arc Really Means

Story Structure #4: How Your Main Character Solves Problems

< Week 3 - Due: Apr.26 >

Project #6 - Research: Shot Progression

Project #7 - Storyboard Assignment: Incredibles

Project #8 - Photoshop: Pixel Art

Story Structure #5: Character Motivation

Story Structure #6: Three Main Aspects of Storytelling

< Week 4 - Due: May.3 >

Project #9 - Research: Shot Progression

Project #10 - Storyboard Assignment: Carnivale

Project #11 - Photoshop: Product Ad Design

Story Structure #7: Your Main Character's Most Personal Issue

Story Structure #8: Impact Characters

Story Structure #9: When the Main Character is Not the Protagonist

< Week 5 - Due: May.10 >

Project #12 - Research: Movie Trailer

Project #13 - Storyboard Assignment: Cinderella Man

Project #14 - Photoshop: Text Effects on Wood Texture

Project #15 - Photoshop: Leather Texture

Story Structure #10: Consistent Plot Points

Story Structure #11: Personal Tragedy

Story Structure #12: Personal Triumph

< Week 6 - Due: May.17 >

Project #16 - Storyboard Assignment: Justice League

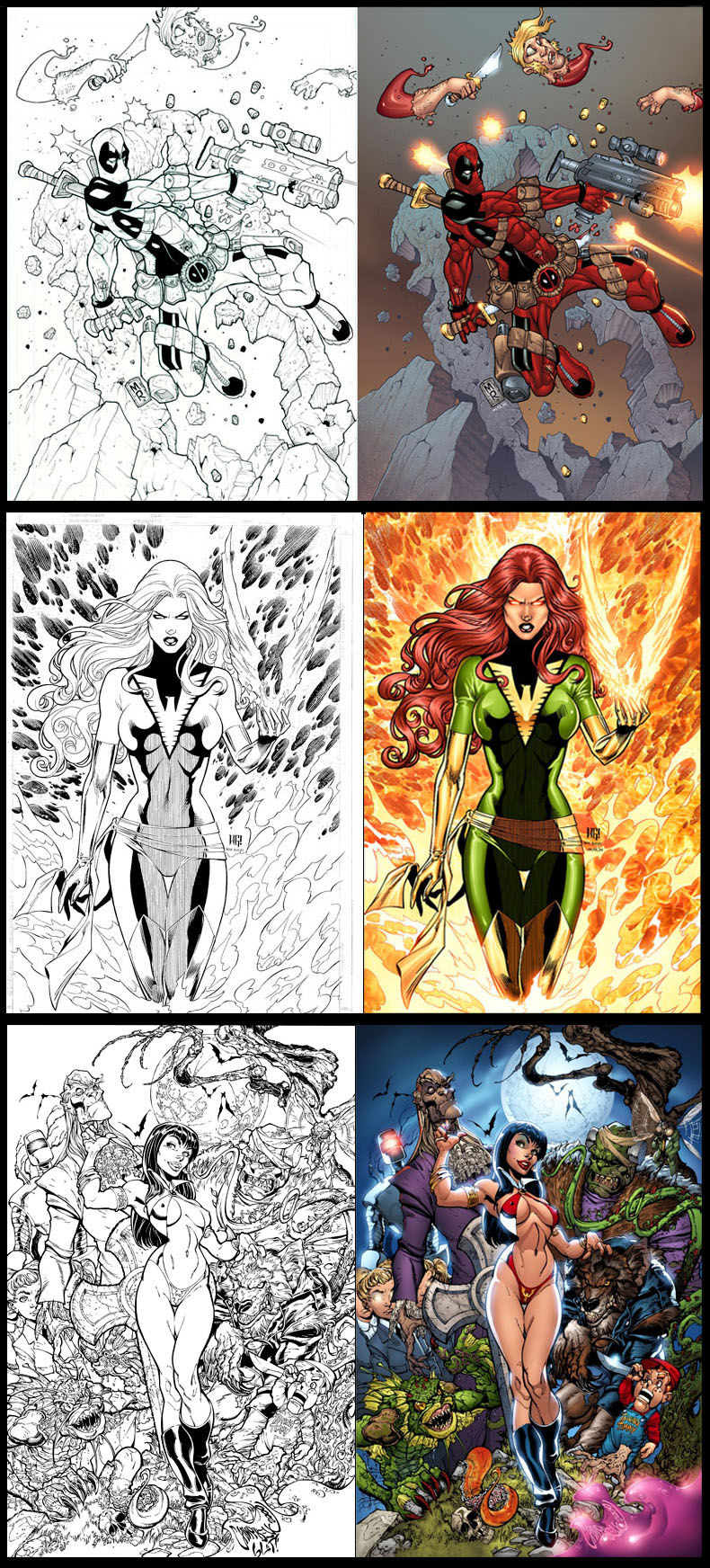

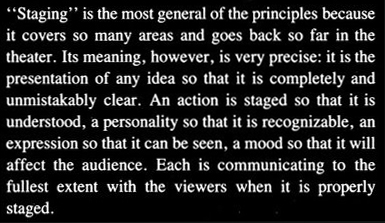

Project #17 - Photoshop: Comic Book Coloring

Story Structure #13: End of a Main Character's Arc

Story Structure #14: A Story is an Argument

< Week 7 - Due: May.24 >

Project #18 - Storyboard Test: Duncan's Revenge

Story Structure #15: Two Sides of the Same Coin

Story Structure #16: The Headline of a Story

< Week 8 - Due: May.31 >

Project #19 - Storyboard Test: Dysfunctional Dam

Story Structure #17: The Most Important Event in a Story

Story Structure #18: The Story Limit

< Week 9 - Due: Jun.14 >

Project #20 - Storyboard Test: The Diamond

Project #21 - Flash: Button-Activated Motion Graphics in Flash

Project #22 - Flash/Photoshop: Build a Self-Contained Flash Website

Story Structure #19: Story Transformation

Story Structure #20: Subtext

< Week 10 - Due: Jun.14 >

Materials for Next Week's Exam

Story Structure #21: How To End a Story

Story Structure #22: Creating Complete Stories

Story Structure #23: The Development of Character & Story

Conclusion

< Week 11 - Due: Jun.14 >

Final Exam: Composition, Storyboarding, Animation Production & Terminology

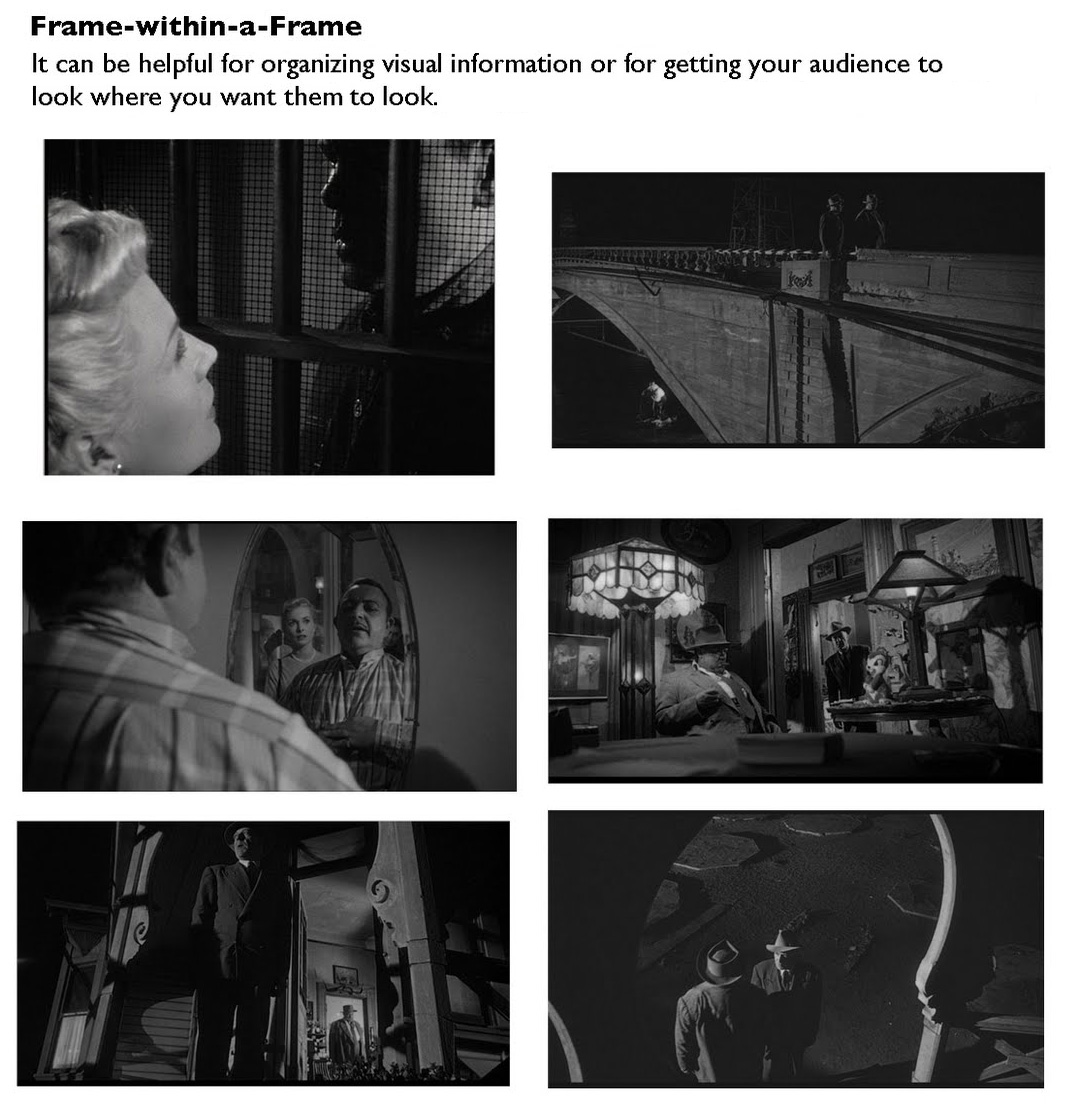

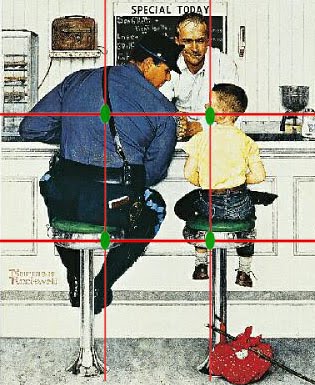

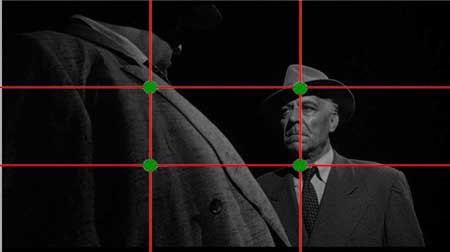

'Framing' can be used within the composition of a shot to help you highlight your main point of interest in the image and and/or to put it in context to give the image some depth.

It also applies in filmmaking:

The perspective that a shot is taken from is another element that can have a big impact upon an image.

Shooting from up high and looking down on a subject or shooting from below looking up on the same subject drastically affects not only the 'look' of the image, emphasizing different points of interest, angles, textures, shapes etc - but it also impacts the 'story' of an image.

There can be a fine line between filling your frame with your subject (and creating a nice sense of intimacy and connection) and also giving your subject space to breath.

Focus on the good stuff. Don't include too much. Extra elements can confuse things. Strengthen your subject by eliminating all unimportant components and background clutter. Either technique can be effective - so experiment with moving in close and personal and moving out to capture a subject in its context.

Sometimes it is what you leave out of an image that makes it special.

The positioning with elements in a frame can leave an image feeling balanced or unbalanced.

Find your balance. Off-center subjects can be balanced on the opposite side of the frame with leading lines, shadows, and objects in the foreground or background. Balance can also be achieved by creating simple geometric shapes. This makes images naturally easier to decipher and more pleasing to the eye. These photos below are a good example of subjects creating a triangular shape (more on this technique later), which brings strong balance and unity to the image.

It is applied in illustration also:

The colors in an image and how they are arranged can make or break a shot.

Bright colors can add vibrancy, energy and interest - however in the wrong position they can also distract viewers of an image away from focal points.

Colors also greatly impact 'mood'. Blues and Greens can have a calming soothing impact, Reds and Yellows can convey vibrancy and energy.

There are patterns all around us if we only learn to see them. Emphasizing and highlighting these patterns can lead to striking shots - as can highlighting ts elemenwhen patterns are broken.

Depending upon the scene - symmetry can be something to go for - or to avoid completely.

A symmetrical shot with strong composition and a good point of interest can lead to a striking image - but without the strong point of interest it can be a little predictable. Mostly, you should experiment with both in the one shoot to see which works best.

Images are two dimensional things yet with the clever use of 'texture' they can come alive and become more three dimensional.

Texture particularly comes into play when light hits objects at interesting angles.

The depth of field that you select when taking an image will drastically impact the composition of an image.

It can isolate a subject from its background and foreground (when using a shallow depth of field) or it can put the same subject in context by revealing it's surroundings with a larger depth of field.

It is applied in filmmaking also:

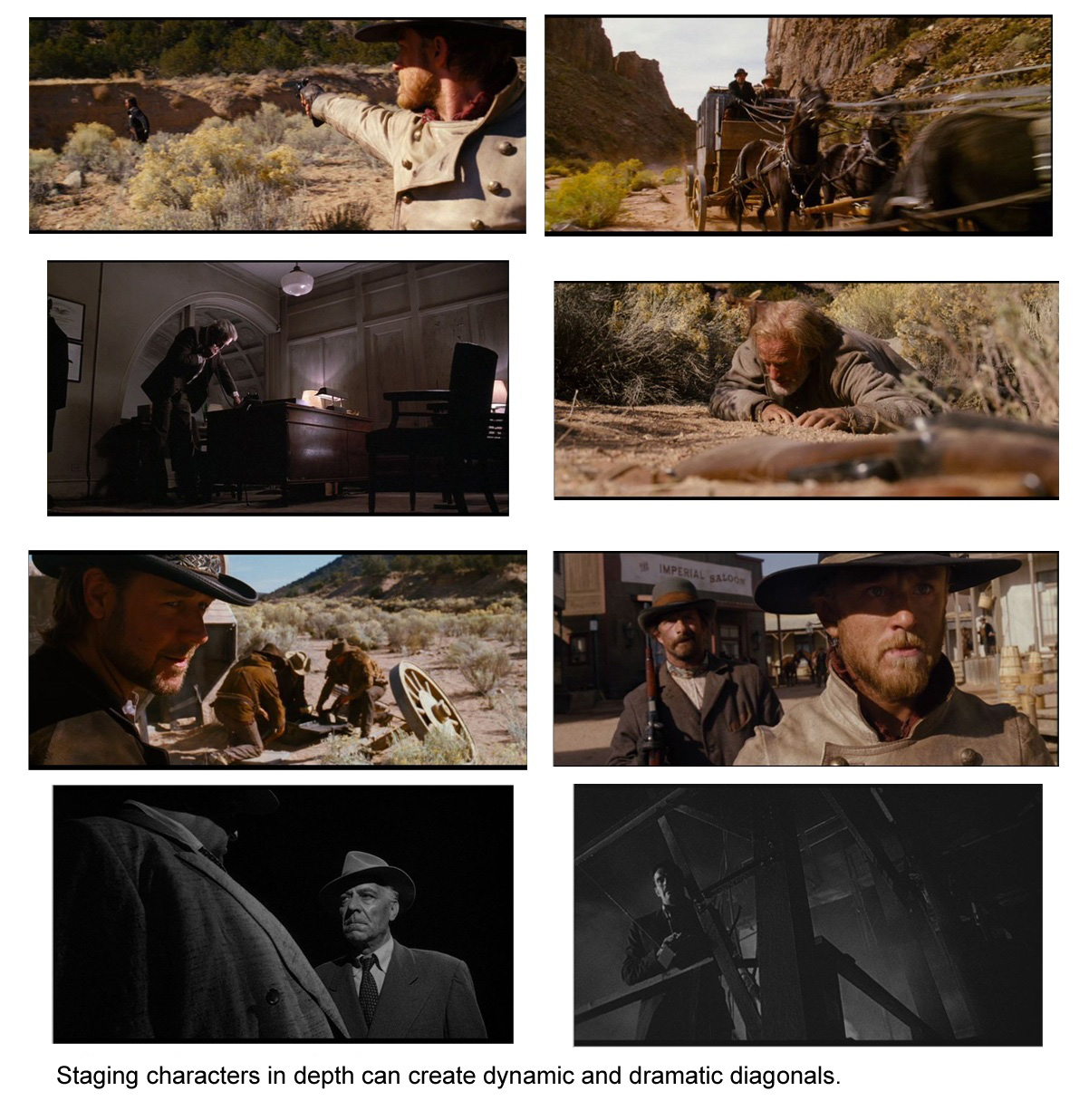

Lines can be powerful elements in an image.

They have the power to draw the eye to key focal points in a shot and to impact the 'feel' of an image greatly. Diagonal, Horizontal, Vertical, d anConverging lines all affect images differently and should be spotted while framing a shot and then utilized to strengthen it.

The key is to remember that in the same way a chef rarely uses all the ingredients at their disposal in any dish - that a photographer rarely uses all of the ingredients of composition in the making of an image.

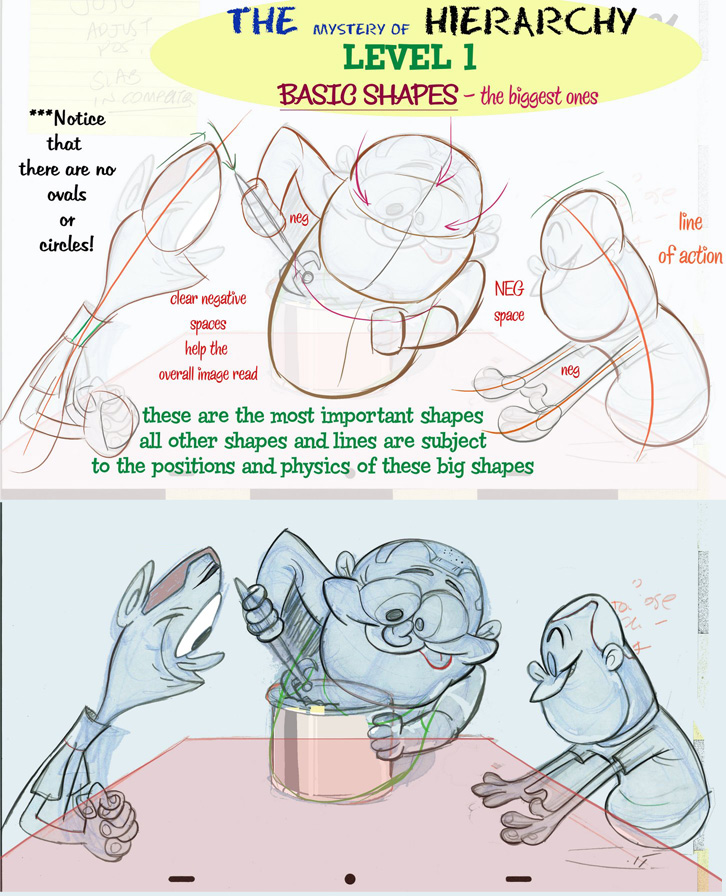

Instead

of starting a picture with small details, they instead have to plan a big

visual statement that reads clearly and simply.

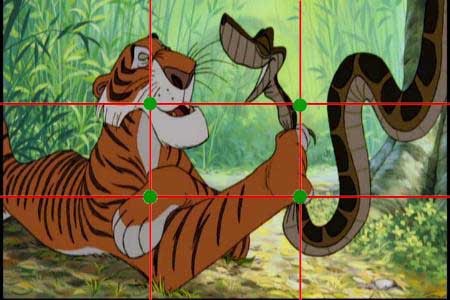

The

overall image above is broken into 4 basic shapes. Then each major shape is

again broken into subdivisions.

Then

the next level.

Someone

with less control would get all absorbed in the details early on. Maybe he'd

start by drawing a bunch of individual leaves and hope they ad up to an overall

tree shape. Or he might do a wild pose of the character - with all the limbs

sticking out in every direction, and no overall silhouette.

Good

storyboard artists have to have this kind of self-control - to avoid getting lured into the details too early. Artists often struggle with composition, because they want to get right to the character first.

Here's

another example. The characters look great, but they fit perfectly into a much

simpler framework, which helps them read well.

Ranger

Smith, Cindy and Baba Looey act as one form, that in turn fits into the bush

shape behind them. They together are well separated from Yogi, who is the focus

of the picture. Boo Boo looks up at Yogi and is framed by the bushes behind

him. If all the characters were evenly spaced and the same size, the picture

would be confusing and wouldn't draw your attention to anything in particular.

The

characters and BG also frame the skywriting plane in the BG.

You

can see this definitive arrangement of shapes in all of Eisenberg's comics.

Great

illustrators like N.C. Wyeth use these exact same principles; only apply them

on more complex levels with more complex drawing:

You

can still see the big shapes dominating the compositions, and the details being

subservient to them through many levels.

Frank

Frazetta has beautiful intricate details in his work, but his images also are

stunning simple compositions. The whole image is a design. He became a master

at composition and hierarchy - so much so that his work is almost a caricature

of artistic control. Everything in his images fits so perfectly together that

it's almost unnatural - even though he is using guidance from a great

observation of nature.

The

differences between Frazetta and good animation cartoonists are in individual

skill and style, not so much in fundamentals. Frazetta can draw much better

than most cartoonists (or anybody else). He also can control more levels of complex

detail, and difficult elaborate structures - like anatomy.

When using Photoshop, your main weapon is going to be the pencil tool (shortcut "B"), which is the alternate for the brush tool. The pencil lets you color individual pixels, without any anti-aliasing.

Two other tools that will come in handy are the marquee tool ![]() (shortcut "M") and the magic wand

(shortcut "M") and the magic wand  (shortcut "W") for selecting and dragging or copying and pasting. Remember that by holding "Shift" or "Alt" while you make your selection you can add or subtract from your current selection. This comes in handy when trying to grab areas that aren't perfectly square.

(shortcut "W") for selecting and dragging or copying and pasting. Remember that by holding "Shift" or "Alt" while you make your selection you can add or subtract from your current selection. This comes in handy when trying to grab areas that aren't perfectly square.

You'll also use the eyedropper ![]() (shortcut "I") to grab colors. Color conservation is important in pixel art for a number of reasons, so you will want to grab the same colors and reuse them.

(shortcut "I") to grab colors. Color conservation is important in pixel art for a number of reasons, so you will want to grab the same colors and reuse them.

Finally, make sure you learn the shortcuts. They can save you a lot of time and energy. A good one to know is "X", which switches your primary and secondary colors.

Pixels are essentially little blocks of color. The first thing you need to learn is how to use these blocks effectively to make any kind of line that you want. We'll discuss the two most basic types of lines; straight and curved.I know what you're thinking - this seems too easy to even bother with! But with these 8-bit graphics-style pixels, even straight lines can be problematic. What we want to avoid are "jaggies" - little breaks in the line that make the line look uneven. Jaggies pop up when one piece of the line is larger or smaller than the surrounding pieces.

For curvature, make sure that the decline or incline is consistent all the way through. In this next example, the clean-looking curve goes 6 > 3 > 2 > 1, whereas the curve with the jaggy goes 3 > 1 < 3.

Being comfortable making any line in pixels is crucial to doing pixel art. Later on, we'll learn how to use anti-aliasing to make our lines look more smooth.

For this assignment, we will be creating a Sprite.1. What will the sprite be used for? Is this for a website, or a game? Will I have to animate this later, or is this it? If the sprite will be animated later on, you may want to keep it smaller and less detailed. Conversely, you can pack as much detail into a static sprite that you will never have to deal with again. But think about where the sprite is going to go, and what will work best.

2. What constraints are being placed on me? Earlier, I had said that color conservation is important. One of the reasons is that, especially if you are working on a game, your palette of colors may be limited. Also consider the dimensions of your sprite and how it will fit with its surroundings.

For this tutorial, I wanted to make sure the sprite was rather large so that you could clearly see what was happening with each step. To that end, I decided to use the Lucha Lawyer, the ass-kickin'est wrestling attorney around, as my model! You can create any object, character or creature you wish.

A black outline will provide a good, basic structure to your sprite, so it's the perfect place to start. The reason we choose black is that it's nice and dark. Later on, I'll show you how you can change the color of the outline for more realism.There are two ways to approach the outline. You can draw the outline freehand and then clean it up, or you can start by placing the pixels as you want them from the start. You know, like "click, click, click".

I think which approach you should use depends on the size of the sprite and your skill at pixelling. If a sprite is very large, it's much easier to sketch the outline freehand to get the general shape and then clean it up later than to try and get it right the first time through.

In this tutorial, we're creating a fairly large sprite, so I'll demonstrate the first method. It's also easier to illustrate with text and pictures.

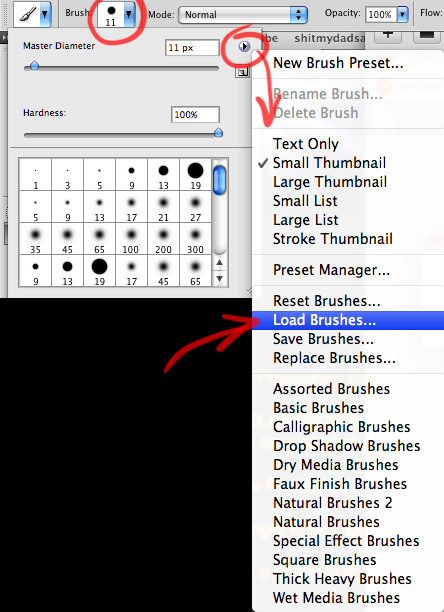

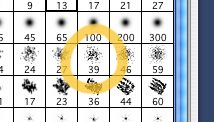

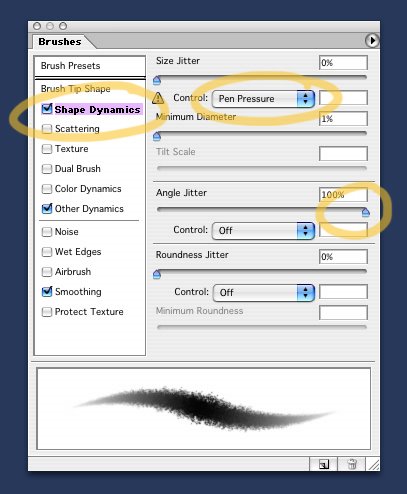

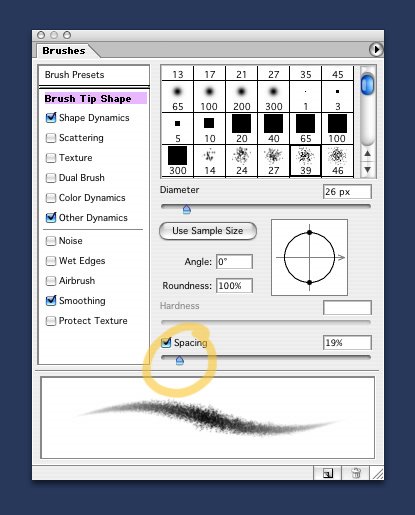

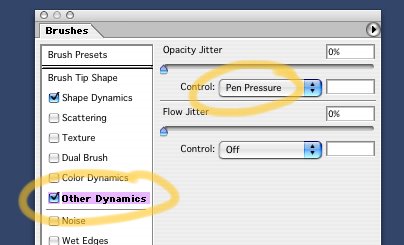

Load the default Square Brushes from the Library that comes with Photoshop, this will give you that hard-edge small square pixel line you want.

![]()

![]()

Even large sprites never usually exceed 200 by 200 pixels. The phrase "doing more with less" never rings more true than when pixelling. And you will soon find that one pixel can make all the difference.

Using your mouse or tablet, sketch out a crude outline for your sprite. You can use one of your own sketches as a rough guide, or use a graphic or image to trace over from the internet, make a new layer and start drawing over top of your rough drawing or image. Make sure it's not TOO crude, though - it should resemble more or less the final product that you want. Either way, keep it simple.

In this case, I'm basing my outline almost entirely on my sketch.

First, crank up the zoom to around 6x or 8x magnification so that we can see each pixel clearly. Then clean up that outline! In particular, you want to trim away stray pixels (the outline should only be one pixel thick all the way through), get rid of any jaggies, and add any small details that were passed over in Step 1.

Keep your outline simple. The details will emerge later on, but for now, concentrate on defining the "big pieces", like muscle segmentation, for instance. It may not look like much now, but be patient.

With the outline done, we have a coloring book of sorts that we can fill in. Paint buckets and other fill tools will make it even easier for us. Picking colors can be a little more difficult, however, and color theory is a topic that is beyond the scope of the tutorial. However, here are a few basic concepts that are good to know.

HSB stands for (H)ue, (S)aturation, and (B)rightness. It's one of a number of computer color models (i.e. numerical representations of color). Other examples are RGB and CMYK, which you have probably heard of. Most paint programs use HSB for color-picking, so let's break it down:

Hue - What you understand "color" to be. You know, like "red", "orange", "blue", etc.

Saturation - How intense the color is, or how intense the color is. 100% saturation gives you the brightest color, and as saturation decreases, the color becomes more gray.

Brightness (or "luminosity") - Lightness of a color. 0% brightness is black.

What colors you choose is ultimately up to you, but here are a few things to keep in mind:

1. Less saturated and less bright colors tend to look more "earthy" and less cartoony.

2. Think about the color wheel - the further away two colors are from one another, the more they will separate. On the other hand, colors like red and orange, which have close proximity on the color wheel, look good together.

3. The more colors you use, the more distracted your sprite will look. To make a sprite stand out, use only two or three main colors. (Think about what just red and brown did for Super Mario back in the day!)

The actual application of color is pretty easy. You want to first select the area you're going to fill with the magic wand  (shortcut "W") and then fill by pressing "G" for the paint bucket and switch between your foreground color and background color with "X".

(shortcut "W") and then fill by pressing "G" for the paint bucket and switch between your foreground color and background color with "X".

First, we have to pick a light source. If your sprite is part of a larger scene, there might be all kinds of local light sources (like lamps, fire, lamps on fire, etc.) shining on it. These can mix in very complex ways on the sprite. For most cases, however, picking a distant light source (like the sun) is a better idea. For games especially, you will want to create a sprite that is as generally lit as possible so that it can be used anywhere.

I usually choose a distant light source that is somewhere above the sprite and slightly in front of it, so that anything that is on top or in front is well-lit and the rest is shaded. This lighting looks the most natural for a sprite.

Once we have defined a light source, we start shading areas that are farthest from the light source with a darker color. Our "up and to the front" lighting model dictates that the undersides of the head, the arms, the legs, etc., should be shaded.

Remember that the play between light and shadow defines things that are not flat. Crumple up a piece of white paper into a ball and then unroll it and lay it on a table - how can you tell that it's not flat anymore? It's because you can see the little shadows around the crinkles. Use shading to bring out the folds in clothing, and to define musculature, hair, fur, cracks, etc.

A second shade, lighter than the first, should be used for soft shadows. These are areas that are indirectly lit. It can also be used to transition from the dark to the light, especially on curved surfaces.

Places that are being hit directly by the light source can have highlights applied onto them. Highlights should be used in moderation (much less than shadows), because they are distracting.

Always apply highlights after shadows, and you will save yourself some headache. Without the shadows already in place, you will be inclined to make the highlights too large.

Shading is where most beginners get tripped up. Here are some rules you should always follow when shading:

1. Don't use gradients. The ultimate newb shading mistake. Gradients look dreadful, and don't even begin to approximate the way light really plays off a surface.

2. Don't use "pillow-shading". Pillow shading is when one shades from the outline inward. It's called "pillow-shading" because it looks pillowy and undefined.

3. Don't use too many shades. It's easy to think that "more colors equals more realistic". In the real world, however, we tend to see things in big patches of light and dark - our brains filter out everything in between. Use at most two shades of dark (dark and really dark), and two shades of light (light and really light) on top of your foundation color.

4. Don't use colors that are too similar. There's no reason to use two colors that are very similar to one another. Unless you want really blurry-looking sprites!

Color conservation is something that pixel artists have to worry about a lot. One way to get more shades without using more colors is to use a technique called "dithering". Similar to "cross-hatching" or "stippling" in the traditional art world, you take two colors and interlace them to get, for all intents and purposes, an average of the two colors.Here's a simple example of using two colors to create four different shades using dithering:

Compare the top picture, which was made using the Photoshop gradient tool, and the bottom, which was created with just three colors using dithering. Notice the different patterns that were used to create the intermediary colors. Try experimenting with different patterns to create new textures.

Dithering can give your sprite that nice retro feel, since a lot of old video games relied heavily on dithering to get the most out of their limited palettes (look to the Sega Genesis for lots of examples of dithering). It's not something that I use very often, but for learning's sake, here it is applied (possibly over-applied) to our sprite.

You can use dithering as much or as little as you want. Honestly, it's a technique that I've only seen a few people use really well.

Self-traced lines, also known as Selective Outlining (or "selout") is the process of shading the outline. Rather than using black all the way around, we apply a color that is closer to the color of the sprite itself. Also, we vary the brightness of this outline along the edge of the sprite, letting the light source dictate which colors we apply.Up until this point, we've kept the outline black. And there's nothing wrong with that, really, since it looks pretty good and it keeps the sprite well-separated from its surroundings. But by using black, we are sacrificing more realism than we might like to, since it gives the sprite a "cartoony" look. Selout is a great way to get around that:

You'll notice I also used selout to soften the folds of his muscles. Finally, the sprite begins to look like a coherent whole rather than a whole bunch of separate pieces.

Compare this to the original:

Generally, you want to add your intermediary colors at the kinks, since that's where the line breaks and looks uneven. If it still looks too uneven, add another, lighter layer of pixels. Have your intermediary layers flow in the direction of the curve.

I don't think I can explain it any better than that without complicating things. Just look at the pictures, and I think you will understand what I mean:

Now let's anti-alias our sprite. Keep in mind that if you want your sprite to look good on any color background, do not anti-alias on it's outer edge. Otherwise, you will see an unfortunate-looking "halo" of your in-between colors around your sprite and it will look nasty as hell.

The effect, as you can see, is subtle, but it makes a big difference.

You may ask why we don't just apply a filter from our paint program to the sprite if we want to make it look smoother? The answer is that no filter is going to make your sprite as clean-looking as if you did it by hand. You have total control, not only over the number of colors you use, but where they get used. And you know better than any filter what areas need to be smoothened out, and what areas are going to lose their pixelly quality if you anti-alias them.

This last part is what separates an ethusiastic amateur from a hardened professional.Step back and take a good long look at your sprite. Chances are, it's still a little rough. Take the time to refine it and make sure that everything is perfect. Give or take how tired you are, this can actually be the most fun part. Add little details to make your sprite more interesting. Your skill and experience with pixelling will show through here.

You may have been wondering why the Lucha Lawyer's eyes have been missing this whole time, or why the supoena he was holding was blank. Well, it's because those were small details that I wanted to save until the end. Also take notice of the trim I added to his armbands, the fly I added to his pants, and... well, what would a man be without his nipples? I also darkened the lower half of his torso so that his left hand would stand out more against his body.

You're finally done! The Lucha Lawyer weighs in at an impressively light 45 colors (or perhaps ultra-heavyweight, depending on your palette restrictions) and has dimensions of approximately 150 by 115 pixels. Now you can have that beer!

Here's an animated .gif that shows the evolution of our sprite:

1. Keep learning the fundamentals of art and practice with traditional mediums. All the skills and knowledge involved in drawing and painting will apply to pixelling as well.

2. Start with small sprites. The hard part is learning how to cram a lot of detail into a few pixels, not making huge sprites (that just takes time).

3. Study the work of the artists whom you admire and don't be afraid of being unoriginal. Biting off other people's work is the best way to learn. It takes time to find your own style.

4. If you don't have a tablet, get one. Repetitive stress injuries from clicking the mouse are no fun and will not impress the ladies (or dudes).

5. Share your artwork with others and get feedback. And who knows, you might just meet some new, geeky friends!

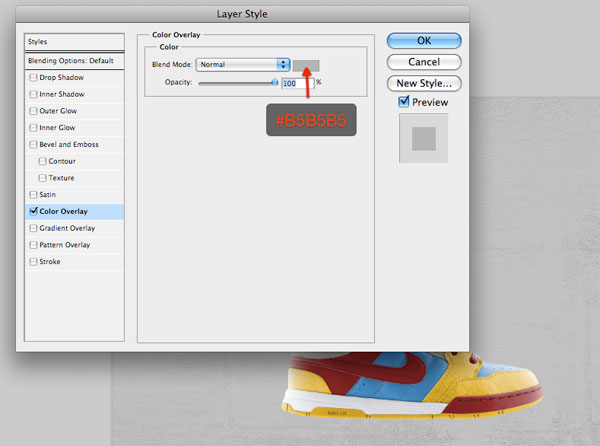

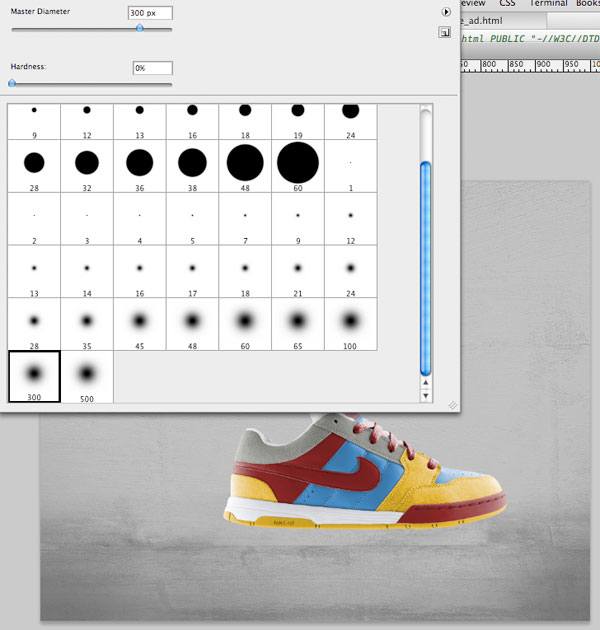

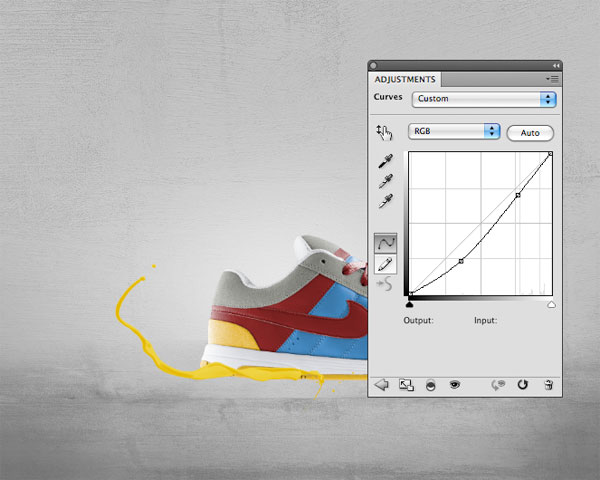

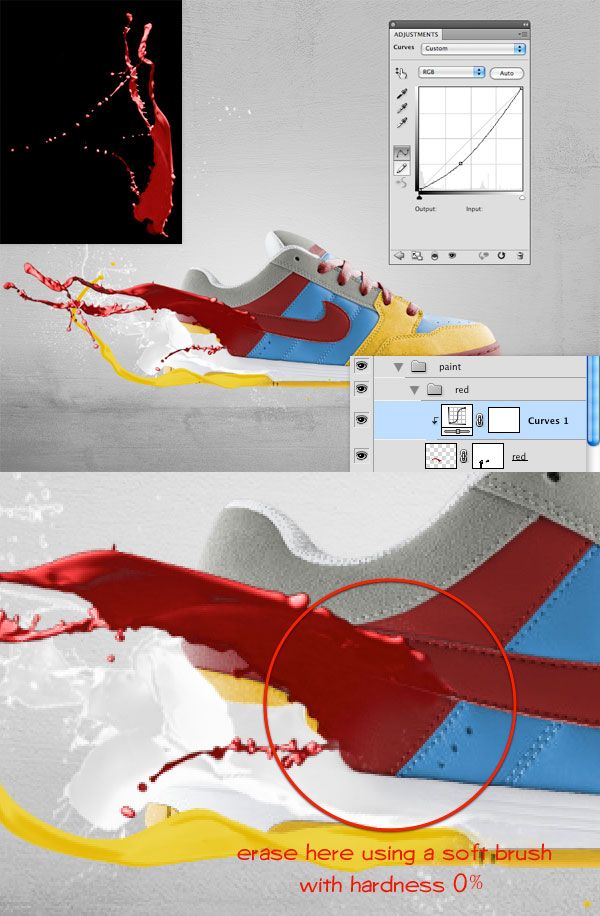

Here is the ad poster design we will create. For this tutorial, I've chosen a classic Nike shoe. You can use any kind of product image and create the same effects. If you want to work with this particular shoe open it from the zip file you just downloaded. If you want to pick your own product make sure you extract it so that it is isolated on its own layer without a background.

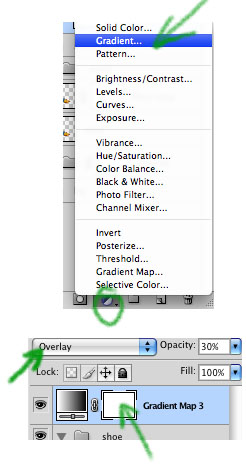

Once you've decided on the poster design's subject (i.e. what article of clothing, electronics or product you'll be featuring), Use the Pen Tool (P) in Paths mode to select around the edges of the shoe. Press Ctrl(or Cmd on a Mac) + Enter (on the layer) to make a selection (or, on your photo, right-click inside the path and then choose 'Make Selection' in the menu that appears), invert the selection (Select > Inverse) and hit Delete to remove its background. This process should isolate our subject for our product ad and prepare us for the next part. Create a new document (Ctrl/Cmd + N) in Photoshop. Mine is 1000ˆó800px with a white background. Once your new PSD is created, paste in the shoe. The focus of our work is the product (the shoe); this is why we will create a soft, unobtrusive background with the goal of making the piece focus into the subject. Extract & Open the texture files from the zip file you downloaded, I picked the second one here, select it, and copy/paste it into your document with ypur product (Ctrl+A Ctrl+C go to your work file Ctrl+V). Press Ctrl+T to activate the Free Transform command and reduce grunge texture's image size to fit our canvas. Place the texture's layer between the shoe layer and the default white Photoshop Background layer. Desaturate the texture by selecting its layer in the Layers Panel and pressing Shift + Ctrl/Cmd + U (or choosing Image > Adjustments > Desaturate). After desaturating the texture, switch its layer's Blend Mode to Overlay. The background will now become completely white because it's overlaid into the white Background layer, but don't worry: we will fix this using blending options. Right-click on the Background layer in the Layers Panel and select Blending Options. The Layer Styles dialog window will pop up. Here, add a grey (#b5b5b5) Color Overlay. After you have added the Color Overlay layer style, reduce texture layer's Opacity to around 30%. Tip: When you resize a texture, lots of small details will be lost. To enhance details on your texture, you can use the Sharpen filter (Filter > Sharpen > Sharpen) if you want. Now that we have a nice grungy background, let's create the floor for our subject. Duplicate the texture layer by right-clicking on its layer in the Layers Panel and choosingDuplicate Layer in the menu that appears. Since the Blend Mode of the original texture layer is set to Overlay, we need to set the Blend Mode of the duplicated layer back to Normal. Afterwards, Press Ctrl/Cmd + T to activate Free Transform and then drag down the top-center transform control to reduce the texture's height as if we are squashing it down - in this way, we are creating the idea of perspective. Next, grab the Burn Tool (O) from the Tools Panel to darken parts of the floor; in particular, we want to darken the bottom corners. The floor is still too prominent - we want it to be more blended with the textured background. In this way, we give depth to the image and the floor looks less distracting. Use the Eraser Tool (E) to remove the top horizon (the top edge of the floor). Choose a large, soft brush with Hardness at 0% for your Eraser Tool. Tip: If you prefer, use a layer mask and a black brush on the floor layer to achieve the same result. To complete the floor, create a new layer on top of it, select a black, large, soft brush and paint over the corners to darken them. Afterwards, reduce the Opacity of this layer to 10%. The aim of this step is to drive the viewer's attention to the center of our canvas where we've placed the product. The background is almost complete. The last touch is a light effect behind the shoe. It's my habit to enhance subjects with light effects - it's a way to embellish the product and draw even more attention to it. Don't forget that the aim of an ad poster is to sell, so we have to do our best to increase the customer's desire to buy it. Even just a few details can make the difference between them looking longer or looking away quickly. For the light effect, start by creating a new layer that is immediately above the background layers. Then use a big, white soft brush and click once on the canvas with the Brush Tool (B) to create the light effect. We will now integrate paint effects into our composition. We will place them on the back portion of the shoe, making it look like as if paint is melting the shoe (hence, "toxic paint"). In order to achieve this result, we need to determine what colors to use by sampling parts of the shoe with the Eye Dropper Tool (I) and we also have to play with their colors to match shoe colors. For this effect, you will need to extract the Paint Tossing Pack from the zip file downloaded earlier. Let's start from the bottom of the shoe (the yellow area). The best option would be to find a paint effect with a simple horizontal-oriented shape. This one (which is part of the Paint Tossing Pack) is perfect for our needs: Open this texture in Photoshop and double-click on the default white Background layer to unlock it. Grab the Magic Wand Tool (W), select the white area by clicking on a white area in the canvas (which should automatically select all white areas), and hit Delete to remove the background. Drag the prepared shape into the main canvas. Activate the Free Transform command (Ctrl/Cmd + T) to rotate and resize the paint shape. Position it on the yellow sole of the shoe. Now we have to make the paint shape yellow; we will use two adjustment layers for this. With the paint shape layer as the active layer in the Layers Panel, choose Layer > New Adjustment Layer > Gradient Map. In order to affect only the paint (and not all the layers that are below the Gradient Map adjustment layer), create a clipping mask (Layer > Create Clipping Mask) on the adjustment layer. Set a color gradient going from a dark yellow (#e9c603) to a lighter one (#f3df71). The paint's color is still too light, so use a Curves adjustment layer (Layer > New Adjustment Layer > Curves) to darken it a little bit so that it matches the yellow color of the sole of the shoe. Finally, create a layer mask on the paint shape, grab a soft, black brush and then use the Brush Tool (B) to erase a small area on the right side of the paint shape so that it looks as if it belongs to the shoe. Other "toxic paint" effects are created using the same method, but applying different adjustment layers. For the white paint shape, I've applied a Black & White adjustment layer to desaturate the shape and a Gradient Map adjustment layer going from a light grey (#d7d7d7) to white (#ffffff) to color it. For the red paint, I've chosen a red paint shape from the Paint Tossing pack that's rotated horizontally with Free Transform. To darken its color, I've applied a Curves adjustment layer. For the grey paint, I've increased its brightness to 70 using a Brightness/Contrast adjustment layer (Layer > New Adjustment Layer > Brightness/Contrast). Secondly, I've added a Gradient Map adjustment layer going from a dark grey (#525252) to a lighter grey (#e6e6e6). Finally, for the last paint effect, I've applied the same adjustment layer used for the Bottom White Paint. Select the shoe layer and create a layer mask on it by clicking on the Add layer mask button at the bottom of the Layers Panel. Once the mask is created, you can use a black, soft brush for the Brush Tool (B) to erase parts of the shoe without losing any pixels (which is great if you want to modify your work, go back to its original state, or if you make a mistake - just delete the layer mask). This will create the illusion of the paints being continuously connected to the shoe. Create a new layer below the shoe layer; we will add a soft shadow effect for the shoe on this layer. The best way is to grab a soft, black brush and paint at the bottom of the shoe. Once you have painted the areas where the shadows are, decrease the layer's Opacity to reduce the shadow's prominence. Create more shadows, but don't just use a single layer to create shadows. I suggest creating different spots on different layers. In this way, you have more control, you can create depth, and you can tweak individual shadow layers to produce interesting outcomes. For example, you can reduce the Opacity of each layer at different values so that the shadow looks more realistic. The ad poster is almost complete. Colors interact in a way that I like. It's simple but vivid at the same time. It's also directed and focused, as a product ad design needs to be. Observing the current composition, I think there's nothing left to change. What we can do better, though, is increasing the poster's color contrasts. To do this, create a new Gradient Map adjustment layer on top of all the other layers. Set the gradient to go from black to white and then switch the adjustment layer's Blend Mode to Overlay. Finally, reduce the layer Opacity until you're satisfied with color contrasts in your composition, an Opacity value of 30%, seems to work well here. To style it up a bit, just add the Nike logo (or ANY logo you wish), in this case I downloaded the logo on a white background, placed it in the document, set the layer to Multiply, and we're done. Save & Open up this wood texture from Zen Textures in Photoshop. Go to Image>Image Size and change the width to 1200px and make sure the resolution is at 72 pixels/inch. This will give us the width that we want for our document. Using the Type Tool (T), create some white text that will roughly fit the width of the document (leaving some space on the edges). I am using ITC Franklin Gothic Heavy for my font, but anything bold should work. Using the Crop Tool (C) crop the top and bottom edges so they have a small margin around the text, about the same amount as the sides or a little more. Click on the eye icon to the left of the text layer to make the text disappear. Go to File>Save, and save it as a Photoshop file. We are going to be using this file later on in the tutorial. Make sure you have the background layer selected. We are going to duplicate the layer with Ctrl+J. Now go to Image>Adjustments>Threshold. Make your threshold level around 70. Go into Select>Color Range, and make sure your fuzziness is at 200. Now with the eyedropper click on a black part of the document and hit OK. A marquee around all the black areas should come up. We want to get the inverse of our selection, so to do that we are going to do Ctrl+Shift+I Now we can click on the text layer and click on Add Vector Mask. Click on the eye icon next to the text layer to bring it back (if it isn't already), and click on the eye icon next to the black and white wood layer to make it go away. If we zoom in we will notice that the masked out parts are too sharp to be believable, compared to the sharpness of the wood. To fix this we are going to go into Filter>Blur>Gaussian Blur. Change the blur to about 0.4px. Now we want to make the edges look a little more believable. First we need to make the mask and the layer just one regular layer, so right-click on the layer and click on Rasterize Layer. Now Right-click on the mask and click on Apply Layer Mask. Now go to Filter>Distort>Displace and change the horizontal and vertical scales both to 2, click OK. A file browser should come up. Open up the file we saved in the beginning of the tutorial. If you zoom in you'll notice the edges follow the lines on the wood background. Drop the opacity of the text down to 80% to give the white part a subtle groove that the wood has. Now we are going to add some lighting effects to our document to make it look a little more interesting. First off, lets create a new layer (Ctrl+Shift+N) and move it above the text layer. Click on the Elliptical Marquee Tool (M) and change the feather to 75px. Now click and drag a circle around the text. We are going to get the inverse selection (Ctrl+Shift+I) of Create another new layer (Ctrl+Shift+N), above the text Change the blend mode to Soft Light and the opacity to 50%. Finally we are going to give our document an overall orange glow. Make sure your foreground is the orange that we used in the previous step and the background is black. Now go into "Create new or fill adjustment layer" (this middle icon at the bottom of the layers palette) and click on Gradient Map. The foreground and background colors should make a black to orange gradient for us. Make sure you click on reverse and click ok. Drop the opacity down to 20% and change the blend mode to Overlay. In today's quick tip tutorial we will demonstrate how to create a leather texture from scratch using a few filters in the right combination.

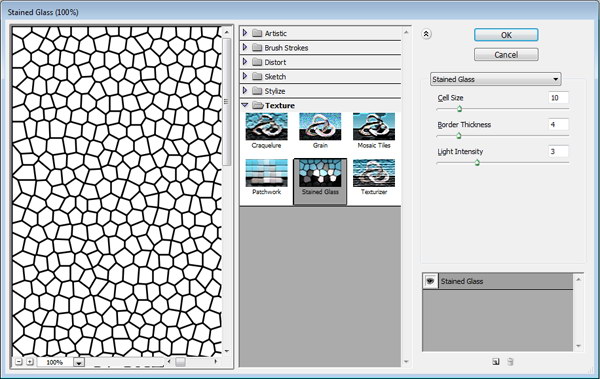

Create a new file with a white background. Set the foreground and background color to black and white by pressing D. Click Filter > Texture > Stained Glass. Create new layer and fill it with white. Change its opacity to 50%. Repeat previous filter by pressing Cmd + F. If you want tweak the setting use Cmd + Alt + F. Press Cmd + E to merge both layers. Click Filter > Noise > Add Noise. Press Cmd + A then Cmd + C to copy all to clipboard. Open Channels panel and create new channel. Then Paste (Cmd + V). Click RGB channel to return to Background layer. Click Edit > Fill, choose Use: Color and pick your color. You can use any color you want, just make sure it's dark enough for the next filter. Click Filter > Render > Light Effects. In Texture Channel choose Alpha 1. The default light is too dark. You need to add more light sources by dragging the lamp icon to the preview box. Set its type to Omni. Click OK and the result should look something like below. Change the background and foreground color to white and black by pressing D then X. Activate the Gradient Tool, choose radial with white to transparent. Create a new layer and draw a gradient. Change opacity to 4%. This will add subtle lighting to the leather. The Lighting Effects filter will add a small border to the image (just a few pixels). To remove it, click Image > Canvas Size and reduce the size of the image. You can change the color by adding an adjustment layer Hue/Saturation. Check colorize and move sliders until you satisfied with the result. That's it. I hope you like the final result and have learned some new techniques from this short quick tip tutorial.

Too many points of interest in one section of your Here's an example of a "busy" picture. The skateboarder is hard to look This shot is very simple. You can see the skateboarder and the Point Of View Leadroom Noseroom

If your subject is in motion, give them plenty of space within the frame to move into. Leading Lines Diagonals Tangents The fence post directly behind the skateboarder is distracting in this Balance Natural Frames Contrast Depth Of Field You might notice that you've As with the article last week regarding why Everything Is Not a Hero's Journey, there also exists a certain group of people that seem to think many popular Protagonists are really just carbon-copies of one another. To them, every central character in a story is simply another evolution of Gilgamesh. Now, to a certain extent, they are right. Luke is more than just a Protagonist. Both Neo (Keanu Reeves) in The Matrix and Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamil) in Star Wars fulfill the role of the classic Protagonist; that is, they are the ones who are pursuing the successful resolution of the story's primary goal. In this purely objective context they do resemble each other. But where their similarity breaks down is in the deeper investigation of what is really going on inside of them personally. Many central characters find themselves faced against apparently insurmountable odds. Many grow to a point where they fundamentally have to change the way they see the world (though this is not always the case). And many find emotional relief from their personal issues at the end of a story ’Äî many reach a catharsis where they overcome that which held them back. When using the above as touch points for examining a story, sure, it looks like every Protagonist is the same. Both Neo (Keanu Reeves) in The Matrix and Luke Skywalker in Star Wars easily fit into these generalized observations regarding story. But that's just it ’Äî they lack specificity. Not only are these concepts of story useless to a writer in figuring out exactly what to do with their story, they also prove to be ultimately detrimental because of their blatant inaccuracies. Constructing a story ’Äî a meaningful story ’Äî is a hard and demanding process. There can be no room for best guesses or gross generalities. Both The Matrix and Star Wars, while similar at face value, really are quite different. One concerned itself with faith, the other with trust. Every Main Character comes to a story ripe with personal baggage. Whether it be some deep psychological issue from when they were a child, or something that just happened to them yesterday, this personal issue ’Äî or problem ’Äî is what motivates them to participate in the larger entity that is a story. Mr. Andersen has a hard time believing. In The Matrix, Thomas Andersen (Neo) suffers from a preponderance of disbelief, both in himself and in the world around him. When asked by Morpehus to climb out on the ledge in order to escape Agent Smith, Thomas doesn't get very far before turning around. "I can't do this, " he claims as he cowers back inside. It is this idea that he is so unpersuadable, both inside and outside of the Matrix, that sits at the heart of Neo's personal struggle. In Star Wars, Luke Skywalker consistently gets into trouble because of his relentless need to test himself. When R2 goes missing, he leaps at the chance to prove his mettle and promptly gets his ass handed to him by the local natives. This flaw haunts him at every turn. In earlier drafts, there was even a sci-fi take on the classic 50's drag race, complete with the requisite scene of Luke pushing his dragster beyond the limits of safety in order to test his abilities against his fellow desert delinquents. This drive to test himself at every turn was Luke's major personal problem. Luke, on the other hand, never had a problem with believing. Clearly these two characters are coming from two different places. Luke never had a problem believing in the Force; he was on-board with the whole thing from the moment he lost his aunt and uncle. Likewise, Neo didn't create problems because he felt this need to test himself all the time; if left to his own devices he probably would have still been there camped out in front of his computer screen. They both were motivated by two distinct and separate problems. Why does this matter? Different problems require different solutions. You wouldn't use masking-tape to hold together soap bubbles anymore than you would use a hammer to make a sandwich. Each problem defines its own appropriate solution and nothing less will than that one particular solution will resolve it. Disbelief requires faith as a solution. Test requires trust. Thomas Andersen eventually grows to a point where he can begin believing that he is, indeed, Neo. Faith resolves his issues. Luke eventually grows to a point where he is willing to let go. Trusting in the Force resolves his issues. Both characters managed to resolve their individual problems by using the correct solution for the issues that plagued them. Now, at first glance, faith may seem an awful lot like trust. Couldn't you argue that Neo was really trusting Morpheus when he decides not to run from Agent Smith? And couldn't you say that Luke started believing in the Force when he turned off his targeting computer? Not really. Neo would not be the superhero he was at the end of the first film if he simply trusted in Morpheus. There was no way he was going to be able to stop those bullets until he truly believed that he could. Similarly, we already established that Luke believed in the Force ’Äî he even had an argument with Han about it back when he was first training on the Milennium Falcon. Luke needed to simply trust in this otherworldly "force" for the torpedoes to hit their mark. Why then is it so important to delineate the exact nature of the problem in a story? Reliance on this is why Star Wars needed Luke. The Main Character's problem represents the finest level of granularity from which one can appreciate the true meaning of a story. That's why an exploration of it can so often seem like splitting hairs. It is important though to make this distinction, because there is so much more that is built on top of the problem, so much more that relies on the accurate understanding of it, that to get it wrong would only cause greater problems in the story at large. The Main Character's problem is intimately tied to the problems suffered by all the characters in a story. It's why this particular Main Character is even in the story in the first place; and it is the answer to the question Why now? so often referred to in story meetings. If for some reason these two problems are at odds (the external and internal), the Main Character may seem out of place, or worse, inconsequential to the resolution of the story. In addition, there will be a discrepancy between the kinds of goals in stories with dissimilar problems. Problems of belief will naturally lead to goals focused on accomplishing some insurmountable task. Problems of trust organically lend themselves to goals more focused on simply doing something. Like the distinction between faith and trust, the distinction between acquiring something and doing something is a very important one. This is why Luke would not have fit into the story that was The Matrix, and why Neo would have had a hard time finding a home amongst the inhabitants of Star Wars. Each particular story goal required a different central character, a different vessel for the meaning of the story. Taking control of the Matrix was the Goal of the story. The goal of The Matrix was to gain control over the software program, to bend it to the will of the humans. Simply fighting Agent Smith and his well-dressed friends was not enough (as evidenced by Morpheus' years of trying). Neo was the lynch-pin for the successful achievement of that goal because the one thing that would allow them to gain that control ’Äî unwavering belief ’Äî was an important factor of Neo's character development. Luke, as described above, had no problem with believing. Trying to replace Neo with Luke would have broken the logic of the story structure and diminished any appreciable meaning. In Star Wars there was no attempt to gain control over the Empire or the tyrannical systems they employed. Instead, there was only the will to find a competent way to fight them. That was the goal of the story. And like Neo, Luke was the key to the successful achievement of that story goal because learning to trust was a crucial part of his individual character development. The only way for the Rebels to successfully fight against the Empire was to trust in something other than themselves. Neo trusted Morpheus from the very first IM he received. To swap him for Luke would have destroyed that story's meaning and shortened the film to about thirteen minutes. These two characters are simply not interchangeable. Not every story is the same. There are tens of thousands of different meaningful story structures, each with its own unique perspective on why things are the way they are. And because each unique story structure requires a specific kind of central character, it follows that there are just as many variations of Main Character. The Matrix was trying to prove how having more faith can lead to greater happiness, while Star Wars was trying to prove that trusting in something other than yourself is the way to go. While looking at them through the lens of the Hero's Journey they might seem the same, the truth is that they carry two very distinct and separate messages. This is yet another reason why the Hero's Journey is a failed device for appreciating the meaning of a story. By definition, everything in a meaningful story is connected. Character flows through plot which flows through theme and finally closes the circle through genre. The machine that is a well-told story is a delicate balance of passionate storytelling and solid logical story-structure. To be inaccurate on even the smallest of matters is to invite failure in the construction of the story at large and a breakdown in the communication of the message the Author hopes to send. Let's revisit one of Christopher Nolan's lesser-known (though not lesser films) The Prestige. Telling the story of two magicians fighting for fame and fortune in the Victorian Era, this 2006 thriller delivers concrete emotional wallop amongst the dark suspense and surprise that is common with Nolan's work. Much of his success can be attributed to the sound story structure he diligently applies to every film. Story structure that, like Inception, gives greater meaning to the events that unfold. One of the precepts for a meaningful story centers around the idea that when looking at the two principal characters one will transformationally change, while the other will remain steadfast. While this may seem to run counter to the widely accepted notion that a character must change in order to arc, it actually speaks of a more accurate understanding of What Character Arc Really Means. Two approaches are presented towards solving the story's major problem, one appropriate, the other not so much. Which one is which is entirely up to the Author and the message they wish to communicate with their audience. When both characters change there is nothing said, no greater purpose to the events on-screen, and therefore, no reason to remember the film some twenty-five minutes later when one pulls out of parking. To a writer, change should be evaluated by comparing the character's final resolve at the end of the story with who the character was at the beginning. If their character ’Äî if the way they look at and see the world ’Äî has somehow become drastically different from where they started, then yes they have had a transformation of character. If on the other hand, they simply grew into a viewpoint they only somewhat believed in at the beginning, then they have actually held steadfast to their worldview. They haven't changed, they have simply grown. One can grow without changing who they are and how they see the world. At first glance it may seem that both principal characters change in The Prestige. Robert Angier (Huge Jackman) changes from a magician unwilling to get his hands dirty (as evidenced by his reticence to kill even the smallest of birds) to a man willing to kill himself over and over again for the roar of the crowd. On the other side of the street, Alfred Borden (Christian Bale) transforms from a man willing to do whatever it takes to keep his magic a secret (as evidenced by the prompt removal of two perfectly good digits) to a man willing to admit the truth of his situation regardless of who he may hurt. So how can both be considered Change characters if in doing so, the story would be considered broken? Ignoring this paradox for a moment, the similarities between the two ’Äî the "You and I" connection, become as equally important in the investigation of this story's structure. Both magicians are driven by that desire for "the Prestige." If the film had been written by an lesser artist, there might have even been an on-the-nose conversation where Angier calls Borden out: ANGIER You know ...you and I ...we're not that all that different. BORDEN And how's that? ANGIER We both would do anything for the sound of their applause. Ugh. As it stands, we do get something close to that in the final reveal scene, but admittedly with more artistry and professsionalism than the ham-handed example above. Regardless, both characters are driven by that desire for recognition, but only one of them truly lets it go at the end. To determine who, it becomes necessary to separate out the individual storylines. It is Angier's desire for adulation that truly defines him. The Main Character's Throughline, while woven into the thematics and plot events of the larger main story, maintains its own concerns and thematic issues. In fact, these dramatic concepts are so unique to this character that he or she would take them with them no matter what story they went into. If Luke had never run into R2 and instead was involved in a story about drag-racing across the dunes of Tatooine (Taladega Wars), he would still have found time to whine about how he was stuck on a planet where his spaceship fantasies could never become a reality. Likewise, if William Munny had never heard of Big Whisky, and instead was involved in the great Oklahoma Land Rush with Tom and Nicole (Far and Unforgiven), he would still have had those issues with maintaining his wife's attitude that he "ain't a bad man any more." If someone were to try and claim one of his stakes, why...well let's just say that Little Bill probably got off easy. Thus, in order to truly understand what is most personal to the Main Character of a story, it becomes necessary to filter out all those elements that really are a part of the larger main story. This is even more important in a film like The Prestige where the Main Character is also the Protagonist not always the case. Far too many times what people think of as a personal moment from the Main Character point-of-view actually turns out to be a choice or action taken from their point-of-view as the primary driver of the main story. If one were to overlook all of Angier's actions as Protagonist (and his goal of trying to understand how Borden does the Transported Man trick), his most personal issues deal with his desire to be the very best, his obsession with the adulation of the audience, and of making them forget their ordinary lives ’Äî if even for a second or two. These are the kinds of issues he would take with him into any story as they are the problems central to his very nature. They coalesce nicely with the rest of the story, but they can be seen as separate and individual and most importantly, personal to him. Scenes where we the audience see the Main Character alone are often chock-full of these sort of personal thematic issues. In The Prestige we get such a moment during Angier's first performance of his own Transported Man trick. Having successfully swapped places with his alcoholic look-alike, Robert takes his triumphant bow from below the stage ’Äî out of sight of the adoring audience but thankfully within earshot. His desire for that love, regardless of how he has to get it, speaks volumes about his character. Another often-used device in communicating this personal throughline is to have another character in the story point out plainly and clearly what the Main Character's real problem is. This is not the same as the Impact Character, who by their very existence in the story forces the Main Character to deal with their personal issues, but rather a character who simply comes out and says, "Hey, you know what your problem is?" David Bowie's Tesla fills this role when he warns Angier of proceeding: TESLA I can make your machine, Mr. Angier. But I can also give you some advice... (pointed) Go home. Forget this thing. I can recognize an obsession. As Mr. Alley could tell you, I myself am given to one now and then. It will not do you any good. ANGIER Have your obsessions done you no good? TESLA At first. But I've followed them too long ’Äî I am their slave. Their whipping boy. And one day they may choose to destroy me. Angier looks into Tesla's eyes. ANGIER If you understand an obsession then you know you won't change my mind. And thus we have a perfect example of a Main Character moment. With these issues at the core of what Angier is personally struggling with it becomes obvious that he grew INTO his resolve, not out of it. His desire began as a small kernel of motivation, but eventually grew into something that consumed him, resulting in his eventual destruction. This was, of course, the meaning behind the whole piece. Angier, therefore, was a Steadfast Main Character. Not ready to get his hands dirty...yet. Resolve, which is what we are concerned with when determining whether a character ultimately changes or stays true to their nature, sits apart from the actual character's growth. Their growth is how they get there, how they end up at that moment of crisis, faced with that choice that will set in stone their resolve. Main Characters can waffle back and forth through the story (and probably should for the sake of interest), but it is that final culminating moment that ultimately defines them. Have they grown to a point where they are ready to let it all go and see the world anew? Or have they determined for themselves that yes, the way they have been going about this is truly the way to go. Angier's need to "get his hands dirty" was something he had to grow into, but was always something he had the potential for. Only then could the audience begin to love him the way he wanted them to. He had moments of doubt, moments when he considered changing, but in the end, in the end he stuck with that desire for fame. Borden, on the other hand, completely transforms his worldview. The key scene for this happens when his wife asks the twin brother (the one more interested in Johanssen) whether or not he really loves her. Since the moment he met her, Borden has been driven to keep up the perception that both he and his brother were one and the same. How else could he successfully pull off the trick of the century without this elaborate deception? The only problem is that this success came with a price ’Äî the emotional torture of his innocent wife. Eventually, and in no small part to his interactions with Angier, Borden comes to a place where he just can't keep it up any longer and reveals to her the truth: INT. LIVING ROOM, BORDEN"S HOUSE ’Äî CONTINUOUS Sarah turns to face Borden. Desperate. SARAH I can't live like this! BORDEN (angry) What do you want from me! Sarah pauses. Catches her breath. SARAH (quiet) I want you to be honest with me. No tricks, no lies, no secrets. Borden calms. Looks into her eyes. Nods. SARAH (CONT'D) Do you love me? Borden looks into her eyes. Sincere. BORDEN Not today. Sarah takes this in. Borden watches, helpless. SARAH (whispers) Thank you. Borden watches her turn away from him. Borden changes to someone no longer driven by illusion. Reality has taken over as his new approach to solving problems and one can imagine that, moving forward, Borden and his brother might choose a different line of work. Unfortunately, in undergoing this transformation of character, Borden breaks Sarah's heart, revealing to her that all along the trick was more important than their relationship. Motivated by this new revelation, his wife feels as if she has no other alternative than to take her own life. In sharp contrast, there is no way Angier would give up that stage for anything or anybody. Separating out the throughlines, determining the difference between a character's resolve and their personal growth, clarifying which principal character transforms and which maintains their point-of-view ’Äî all of these are tools a writer can use to insure that their story stays consistent and meaningful throughout. When writing a story as complex and non-linear as The Prestige, understanding precisely what is going with the characters that populate it can go a long way towards making sure the audience does not leave befuddled or overcome with unanswered questions. Those who prefer to leave such concepts left to chance, or to the whims of their individual muse, aren't really looking close enough because really...they don't want to know. They want to be fooled. Every problem has its own genesis, a moment at which the balance is tipped and the previous sense of oneness is lost. With separation comes the awareness of an inequity, and a desire to return back to a state of parity. Every problem has a solution, and a story explores that process of trying to attain resolution. In a story, this Opening Event ’Äî or beginning of a story ’Äî is commonly referred to as the Inciting Incident. The Inciting Incident (or "exciting incident" as someone once referred to it) is the event or decision that begins a story's problem. Everything up and until that moment is Backstory; everything after is "the story." Before this moment there is an equilibrium, a relative peace that the characters in a story have grown accustomed to. This incisive moment, or plot point occurs and upsets the balance of things. Suddenly there is a problem to be solved. Stories are about solving problems. Sometimes they are solved, as is the case with Star Wars, Casablanca or Inception. Other times, as with stories like Hamlet, Amadeus or Se7en, they aren't. Regardless of outcome, this Inciting Incident gets the ball rolling by introducing an inequity into the lives of the characters that inhabit the story. The Protagonist seeks the solution, the Antagonist seeks to prevent it. Every story works this way. The two central objective characters, Protagonist and Antagonist, battle it out until approximately one-quarter of a way into a story, some other event or decision occurs that spins the story into a brand new direction. This second plot point is referred to as the First Act Turn as it turns the story from the First Act into the Second. This is a further development of the problem, not the beginning of a problem. Other plot points ’Äî the Mid-Point and Second Act Turn ’Äî continue to escalate the issues surrounding the efforts to resolve the problem until finally, the Concluding Event, or Final Plot Point, ends the story. As mentioned above, this does not necessarily mean the problem has been solved. It simply means that the efforts that were undertaken by the Protagonist have come to their natural end as every resource has been exhausted. These plot points naturally split a story into four parts. For fans of Aristotle, the first part is the Beginning, the second two are the Middle and the third is the Ending. There is a meaningful reason why there are four parts. In short, for every problem there are four basic contexts from which you can explore the way to solve a problem. Once you have explored all four contexts, the story is over. Any continuation would simply be a rehash of something that has already been investigated. The most important thing to take away from all of this is that the First Act Turn is NOT the Inciting Incident. This is a common mistake by many first time writers, and is generally caused by a lack of understanding exactly why these plot points exist in the first place. One plot point starts the problems, the other furthers the complications of said problem. The following is a list of great stories with their corresponding Inciting Incidents and First Act Turning Points. The numbers provided are either based on page numbers, Kindle percentages or minutes depending on what source material was easily accessible. For those who don't know, the general idea is that one page of a screenplay generally lines up with one minute of screen time. A 120 page screenplay often lasts two hours on screen. or 120 minutes. Thus, the Inciting Incident would occur on or near page 0, while the First Act Turn would happen somewhere near page 30 (out of 120). If we're talking percentages, that would be about one-quarter of the way into a story. The Inciting Incident of Star Wars is Darth Vader's attack on Princess Leia's ship (1/120). While there was a civil war going on prior to this event, it isn't until the Empire shows its true colors by illegally boarding a ship purported to be on a "diplomatic mission" that the real problems of the story begin. The Empire has grown ruthless in its efforts to contain any rebellion, this inciting event is only the beginning of many more to come. The First Act Turn begins with the Empire's sinister agents attack on peaceful Jawas and ends with their barbeque of Uncle Owen and Aunt Beru (30-31/120). Suddenly, what began as a simple conflict over jurisdiction has now turned into an all-out rampage that affects even the most remote and more importantly, innocent, members of the galaxy. The problem has grown in its potential for even greater conflict. The Inciting Incident of The Matrix is Morpheus' decision that Mr. Andersen is the One they have been looking for (2/130). This one decision drives the entire rest of the story, for if he hadn't picked Tom the rest of the world would have stayed comfortably numb in their battery pods. Without the Inciting Incident, there would be no story. The First Act Turn begins with Neo's decision to come in off the ledge (21/130). It isn't until this true sign of character that Morpheus is forced into taking even greater strides to break poor Mr. Andersen out of the Matrix. These deliberations by Neo ’Äî continuing with his "giving the finger" scene, choosing whether or not to stay in the car, and culminating with his decision to take the red pill ’Äî all create resistance to Morpheus' initial selection. It isn't until Neo finally decides that he is the One (121/130) that the problems in the story come to a successful resolution. The Inciting Incident of Unforgiven is Little Bill's leniency towards Quick Mike (5/120). Little Bill is known for dealing with criminals in his own special way, why the sudden change of heart? His refusal to respond in kind creates a rift within the story at large, and forces the whores to seek out their own justice. The first Act Turning Point only makes matters worse with the arrival of English Bob and his refusal to surrender his sidearms to "proper authority"(33/120). The Inciting Incident of The Sixth Sense is Vincent's attack on Malcom (8/109). Without this gunshot, there would be no story and no compulsion for Malcom to meet with Cole. The First Act Turning Point comes with Cole's revelation that he might suffer from the same violent tendencies that Vincent did. His steps back and his conclusion that Malcom can't help him only furthers the problems caused by the perception that Cole is merely a "disturbed" child (22/109). The Inciting Incident of Casablanca is Ugarte's decision to give Rick the letters of transit (15/127). While the murder of the two couriers seems to get things rolling, problems don't really start until Ugarte decides to give them to Rick. After all, people get murdered in Casablanca all the time. But give them to someone whose allegiances are in question? Now we've got a problem. These papers and the efforts to retrieve become the major source of conflict for everyone involved in the story. This is why Rick's deliberations over what to do with them, including his refusal to help out Ugarte ("I stick my neck out for nobody"), propel the First Act into the Second (30-45/127). With Rick in charge of who gets them and when, Laszlo's mission becomes that much more difficult. The Inciting Incident of The Lives of Others is Minister's Hempf's decision to have Georg Dreyman "watched." (10/135). Without this bigwig's desire for Dreyman's girlfriend, Wiesler would have continued his life as he always had, and quite possibly would never have crossed paths with this writer and his friends. Like Casablanca, the First Act Turn comes more as a wave than an actual singular event. This time it is Dreyman's best friend, the director Albert Jerska, and his constant ruminations over the purpose of his life that progressively complicate a simple spy operation into something far more reaching and grander in scope. Jerska's dark contemplations of suicide inspire Dreyman to write and give reason for Wiesler to better understand the kind of struggles and torment these artists go through as a result of the state's actions. And finally, the Inciting Incident of The Incredibles occurs with the overwhelming flood of lawsuits stemming from Mr. Incredible's loss in court against Oliver Sansweet, the man he rescued from suicide (14/127). This rush to sue forces the Supers into hiding, promising "to never again resume hero work." These previously costumed guys (and girls) now can't be who they want to be, and thus yet another story inequity has been created. If it had just been Sansweet, then perhaps things would have simmered down. The flood of lawsuits tipped the scales. Problems escalate when Bob and Frozone almost get caught during the fire in the apartment building sequence (32/127). Before, Bob had found a way to deal with the initial problem by moonlighting with his best friend. This event, and their near apprehension by local authorities, forces Frozone to decide that this night was the last one. What was once a manageable problem has now become an even bigger one, and eventually provides the motivation for Bob to accept the mysterious invitation from Mirage. Plot points drive a story towards the resolution of its problem. Even Bill understood the connection between the first two plot points. But what about other forms of narrative fiction? Surely this is just a "formula" for Hollywood-wannabes to follow... Story is story regardless of the delivery device. The Inciting Incident of Shakespeare's Hamlet is the death of Hamlet's father. As with The Matrix, where the actual inciting event happens "off-screen", the story immediately opens up with the characters plagued by the problem's effects: Quick tranlsation: Hamlet has been thrown into great despair because of his mother's impulsive move to quickly marry his father's brother, Claudius (10%). The fact that she couldn't even wait a month drives Hamlet mad, thus creating a problem in Elsinore that calls for some sort of resolution. This problem grows in importance when the Ghost of Hamlet's father informs his son of what really happened: No longer an inequity that must be suffered, the death of Hamlet's father now becomes something that must be avenged (20%). The dramatic energy produced by the news of his father's passing has waned to the point where something new must come along and drive the story further towards its inevitable conclusion. This revelation of a "murder most foul" is that event, and can be considered the First Act Turning Point of the play. Determining the events or decisions that escalate a story's problem should be Job One for the working dramatist. It is one thing to create an opening scene that wrecks havoc on the characters in the film and forces them to deal with this new problem, quite another to ensure that the inequity persists until the closing curtain. Eventually, as with Hamlet, the potential for dramatic conflict will decline throughout the course of an Act. It is the same drop in potential that one feels as the pain from a pinch or slap in the face subsides over time. In order for the problem of a story to continue to drive the characters towards an eventual solution, a new potential must be introduced. These new dramatic forces, escalating the problem beyond that initial blast, drive the story forward in such a way that the characters themselves could never return to who they were or what they did during that first initial response. There can be no turning back. Act turns exist to re-energize the potential of a story's problem, not to satisfy page-counting readers or paradigm-happy script gurus. Connecting the two first plot points to this problem, and making sure that they aren't simply the same event, will give an audience something to engage in and something to become invested in. The fact of the matter is that no audience member can resist the draw of the problem solving process as it unfolds on the big screen; it's human nature to see what greater meaning can be gained from how the resolution plays out.

Project #11

Photoshop: Product Ad Design

Resources

Step 1: Preparing the Product

Step 2: Create a New Photoshop Document and Place the Subject

Step 3: Add the Background Texture

Step 4: Enhance the Background Texture

Step 5: Create the Floor

Step 6: Create a Light Effect Behind the Shoe

Step 7: Create a "Toxic Paint" Effect

Prepare the Yellow Paint Shape

Bottom White Paint

Red Paint

Grey Paint

Top White Paint

Step 8: Refine and Enhance the Shoe with a Layer Mask

Step 9: Add Shadows on the Shoe

Step 10: Perform Final Refinements

That's it!

Story Structure #7

Your Main Character's Most Personal Issue

To get a different perspective on what is really going on in your story you need to view your story (the script, the storyboard) and impartial and unbiased, this can be difficult to do, the more involved you are in the development of the story, both how it is written and how it is visually displayed, the more difficult this can be. You should not change how these main concepts of storytelling work, just the way you approach them. In doing so, you'll find different questions to ask yourself about your story itself.

The Main Character's Throughline is the one spot where you can get a broad overview of what is really bothering the main character. While the further down the chart you delve the more precise you can be about your writing, you also risk confusion as the differences between things gets smaller and smaller. Better to stay at the top until you really feel confident with the kind of issue your Main Character is dealing with.

Think of your Main Character's most personal issue - that issue that they would take with them into any story, regardless of what happens around them. Got it? OK, now ask yourself these questions:

* If her situation improved, would she be happier?

* If her mindset improved, would she be happier?

* If the way she engaged in activities improved, would she be happier?

* If the way she thought about things improved, would she be happier?

All of these may pertain to your Main Character, but only one of them will feel really right.

Perhaps she's an underpaid factory worker who thinks only the rich can get richer. If she was paid a decent rage would she be better off? Not really, because it wasn't her situation that was holding her back, it was her defeatist attitude that class dictates providence.

Or maybe she's a struggling pianist stricken with such an awful fingering technique that she spends most of her days trying to bury her love for classical music. Wouldn't she be happier if she just realized things are what they are and instead embraced her passion for Bach? No, she'd continue to be miserable with every missed key. On the other hand, with a little extra time spent practicing her scales, she might find herself loving the classics even more.

Asking yourself these questions will help you nail down the source of your Main Character's issue. With that information in hand, you can then spend time writing scenes that develop on that issue and either have your Main Character work through resolving it or leaving it to fester. Either way, you'll have the confidence knowing where your Main Character is coming from to write effectively and consistently.

Story Structure #8

The Impact Character

The Second Most Important Character in a Film

Everyone agrees that the Main Character is the most important character in a film. Why? Because through this person, an audience experiences first-hand the emotions and consequences of the narrative surrounding them. But there is another, less understood character that is primarily responsible for influencing growth in the Main Character. This character is known as the Impact Character.

When the Impact Character is steadfast, then he will make his arguments to the Main Character in reference to his own drive. He will treat his own drive as if the same things should be driving all others as well.

This often pops up in conventional arguments where the Impact Character says to the Main Character, "you know, we are just like, you and I," (if the IC is steadfast) or "we are nothing alike," (if the IC changes)."

Is that true? Is it really that black and white? "We're alike" if the Main Character changes and "We're nothing alike" if the Impact Character changes. Is it really that easy?

Overall, we should understand that this is a generality and therefore shouldn't be taken as a strict rule of dramatic narrative, but it started me thinking. How did this generality hold up under further scrutiny? And more importantly, could it help me with my own work?

I took six Impact Characters, three who Change and three who Remain Steadfast, and applied the above concept.

Change Impact Characters.

Score one for Marshall Samuel Gerard. Chasing Richard Kimble (Harrison Ford) in and around Chicago I could hear Tommy Lee Jones uttering "We are nothing alike Richard." Gerard is not the type to suggest that he and a fugitive wanted for murdering his wife are anything alike. It would be quite strange to hear him say so.