"How clean does a cleaned-up storyboard have to be?"

Click here to see new material.February 1, 2020

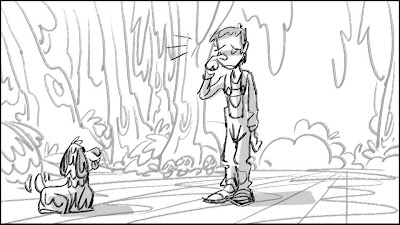

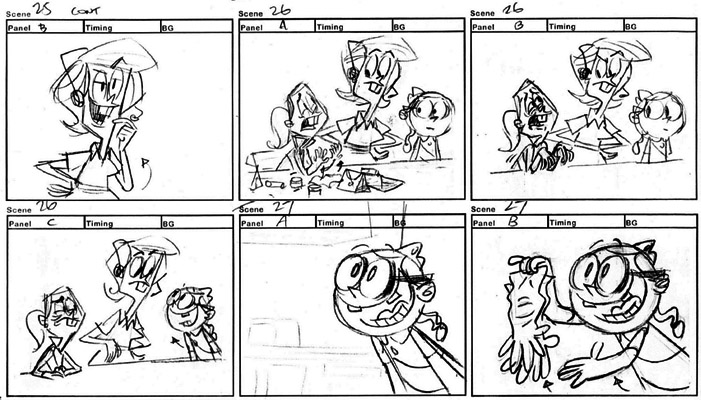

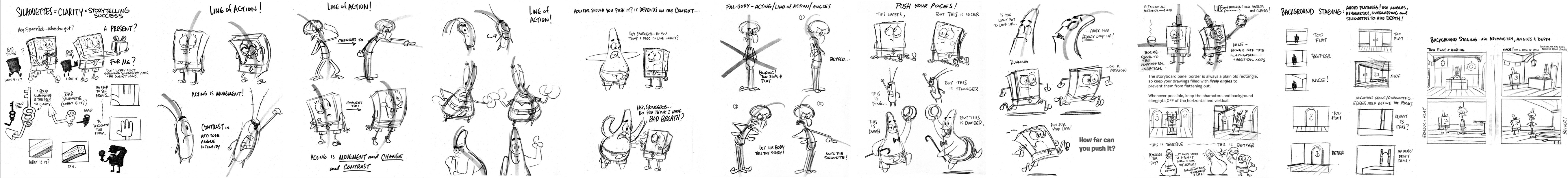

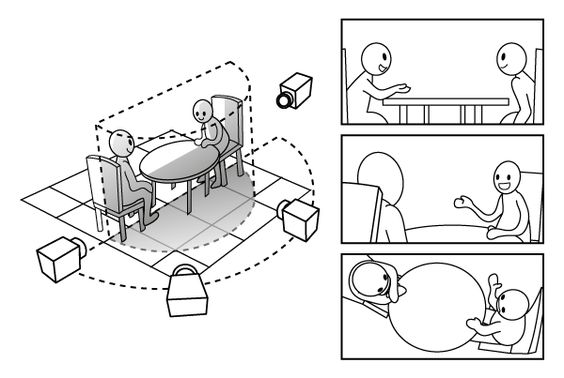

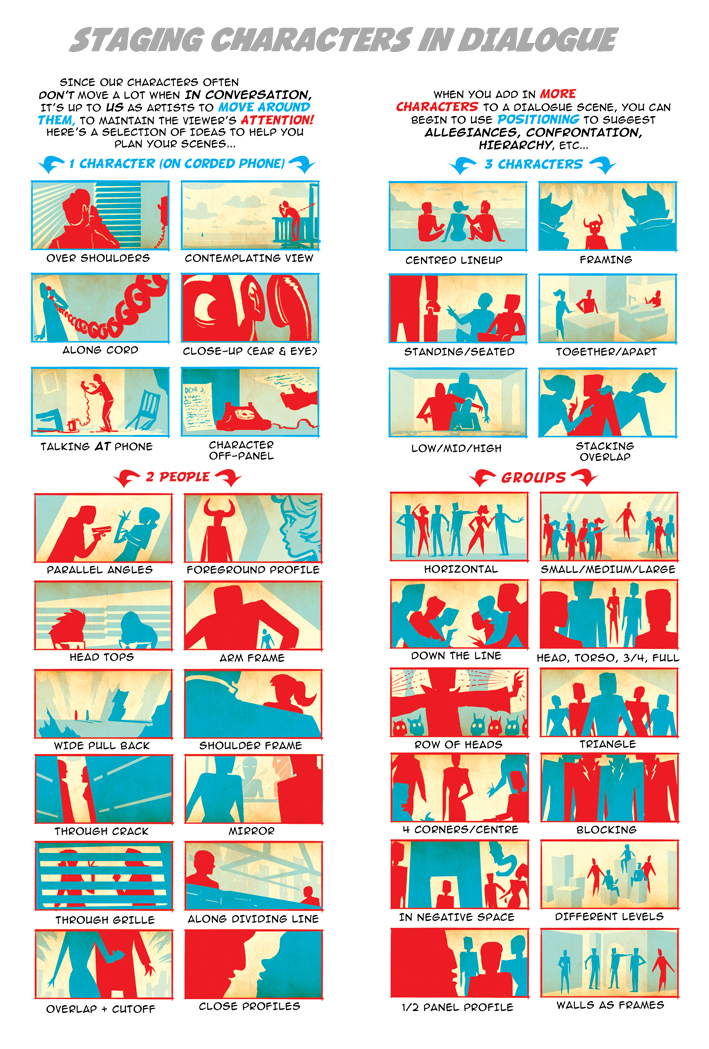

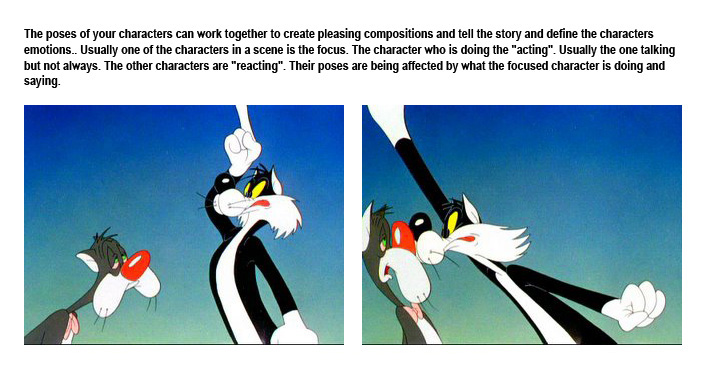

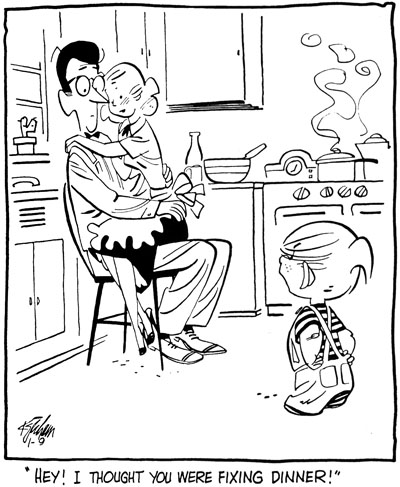

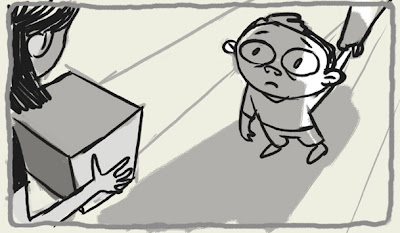

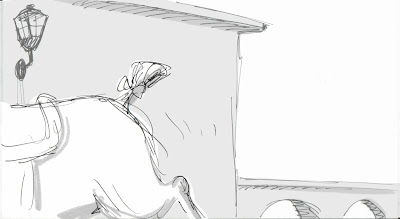

Often I find that the point of the story is being lost simply by unclear staging. To the left is an example of a scene in which a boy is showing his mom he got an F on a paper at school. The boy is giving excuses at this point in the story and fearful of his mom's reaction. Though the staging is interesting the focus has been put on the mom. This is a great opportunity for some acting on the boy but it's missed and most likely will have a long paragraph worth of dialog assigned to this single panel. Many times I will see a panel like this with both the boy's and the mom's dialog set to it. No matter if you are creating the dialog or it's coming from a script, you need to look for opportunities for acting where you can give the audience a chance to know your character.

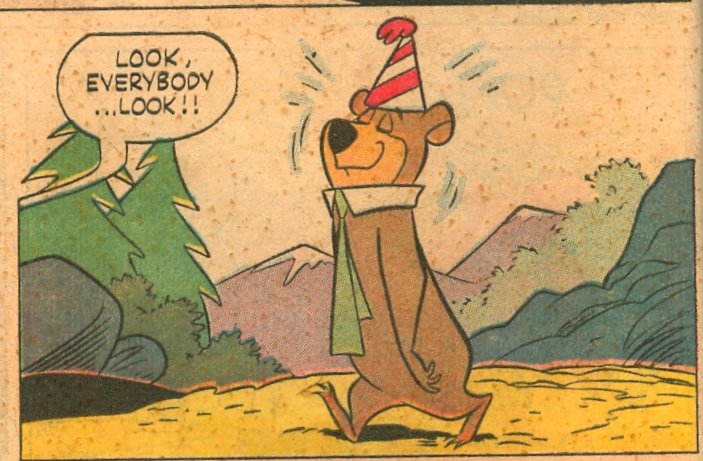

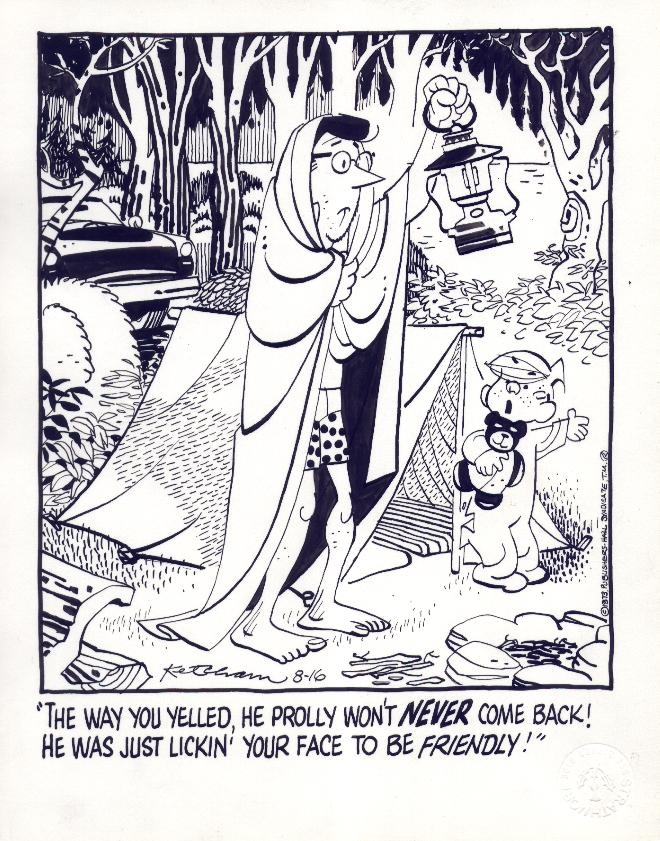

Often I find that the point of the story is being lost simply by unclear staging. To the left is an example of a scene in which a boy is showing his mom he got an F on a paper at school. The boy is giving excuses at this point in the story and fearful of his mom's reaction. Though the staging is interesting the focus has been put on the mom. This is a great opportunity for some acting on the boy but it's missed and most likely will have a long paragraph worth of dialog assigned to this single panel. Many times I will see a panel like this with both the boy's and the mom's dialog set to it. No matter if you are creating the dialog or it's coming from a script, you need to look for opportunities for acting where you can give the audience a chance to know your character. To the right is an alternate staging for the same scene. It gives the boy a chance to act and it's easy to tell right away what the scene is about. I would probably add several panels of acting in this same staging.

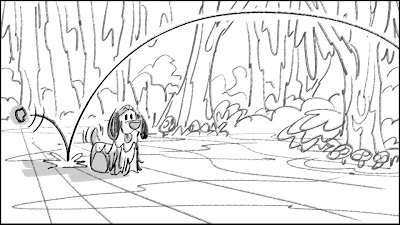

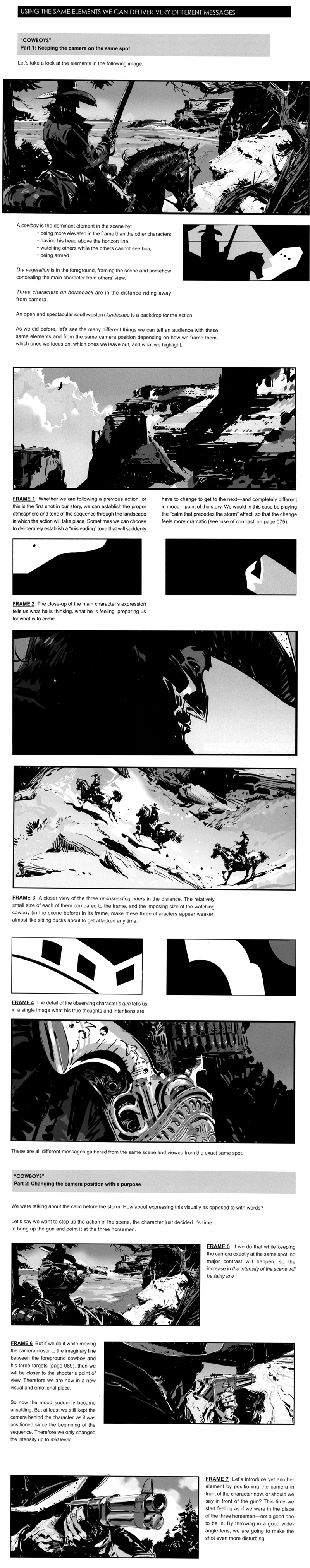

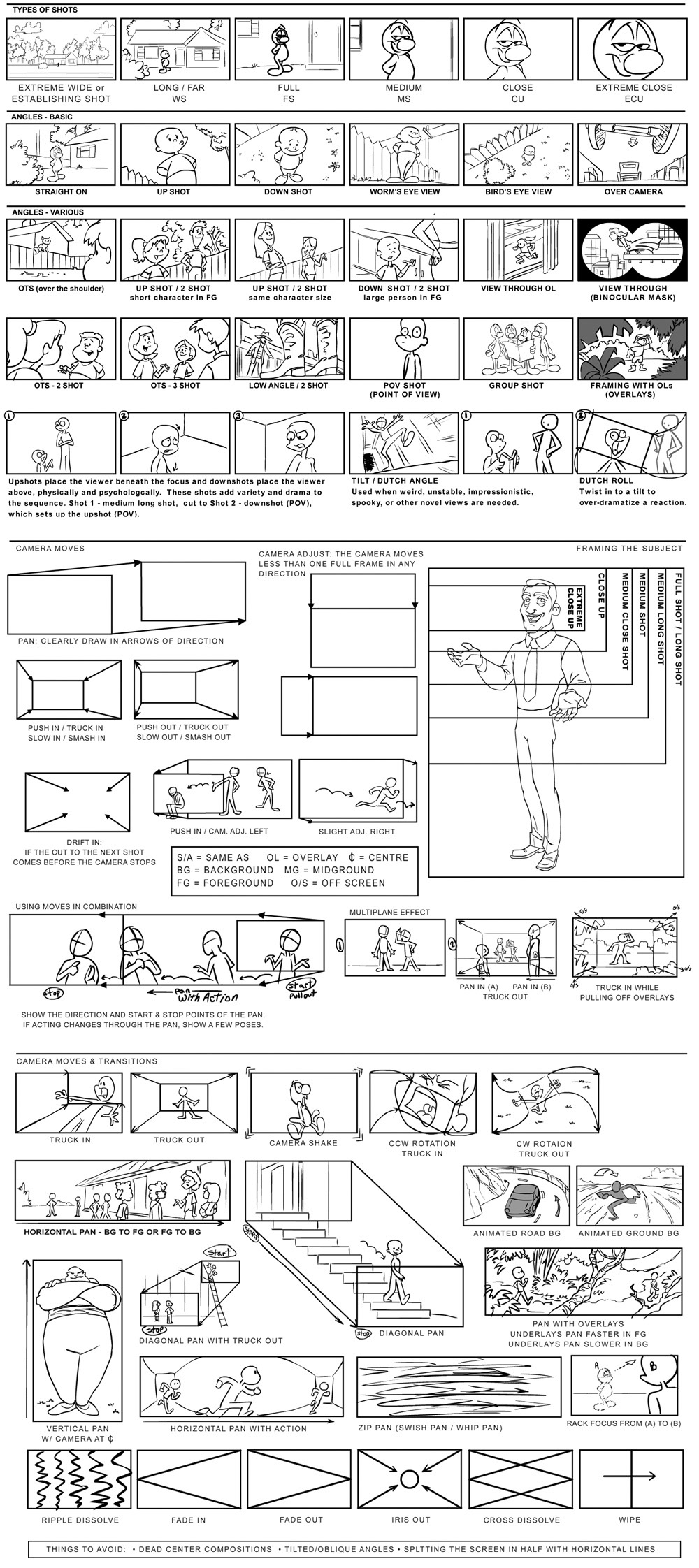

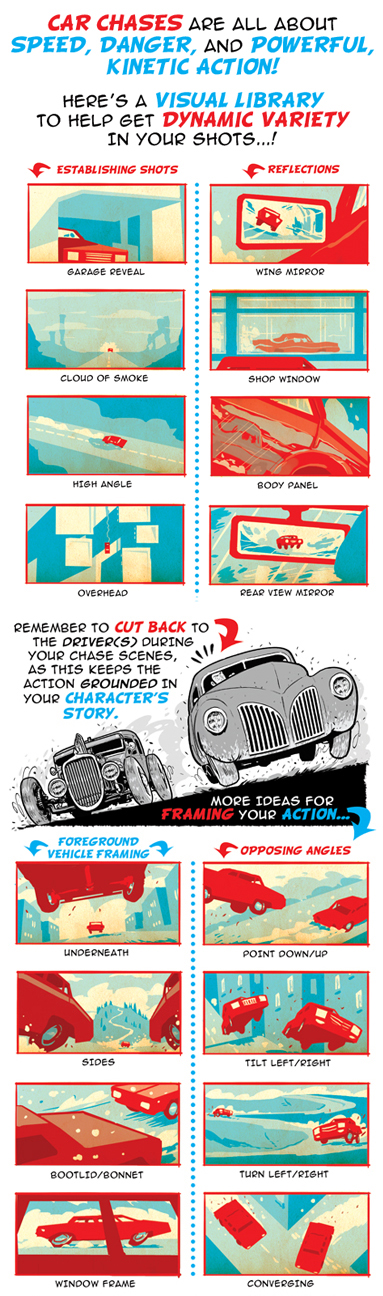

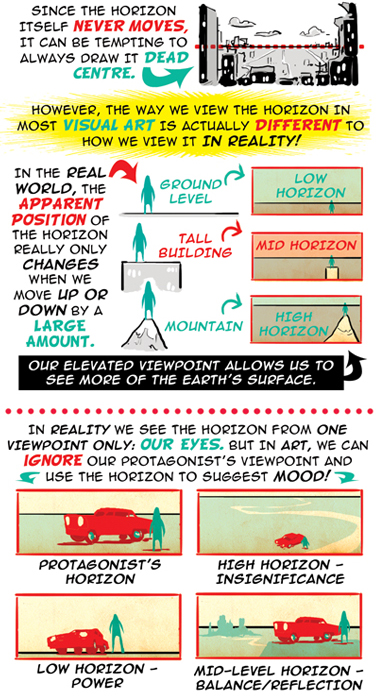

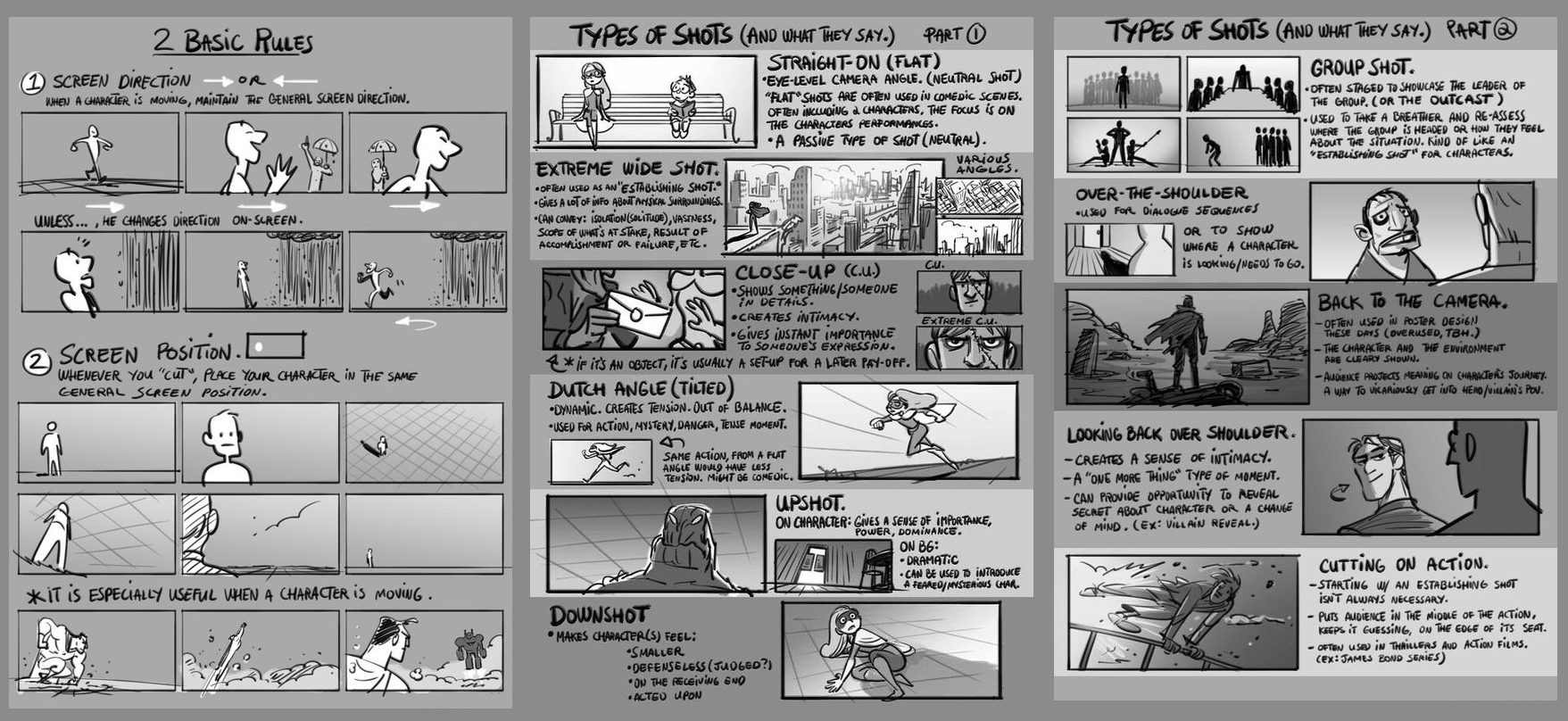

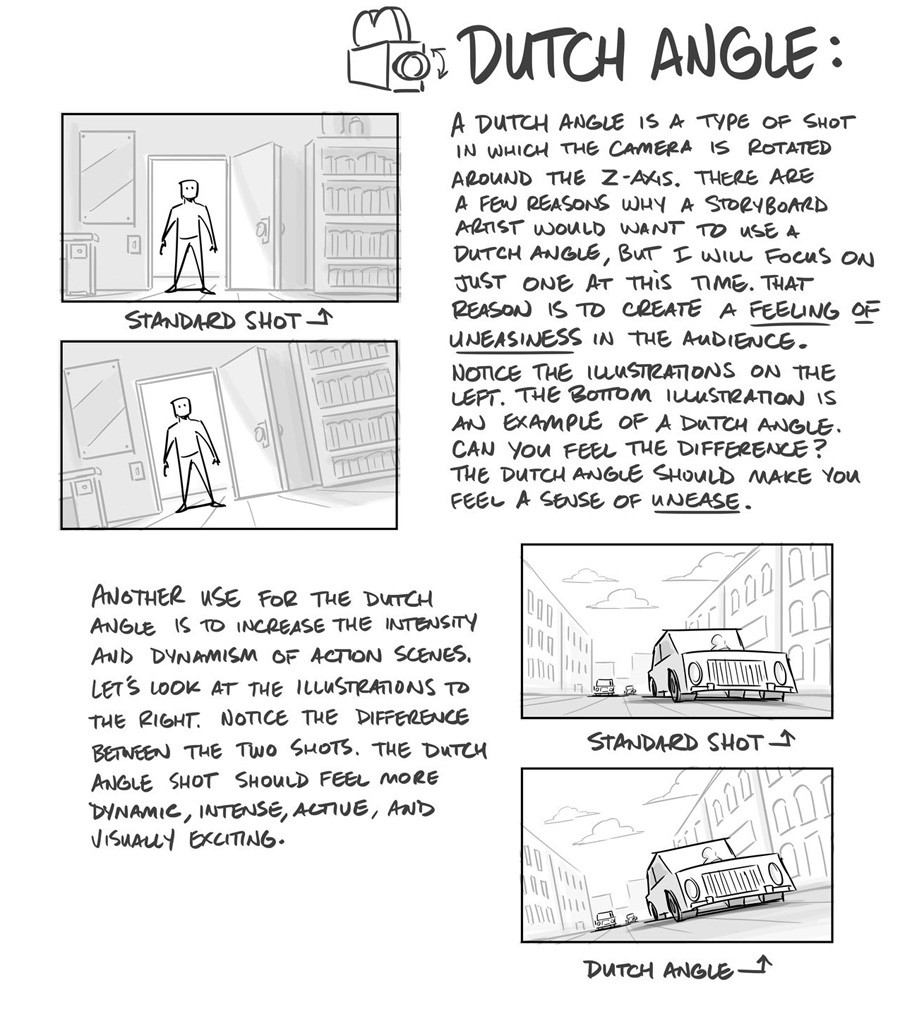

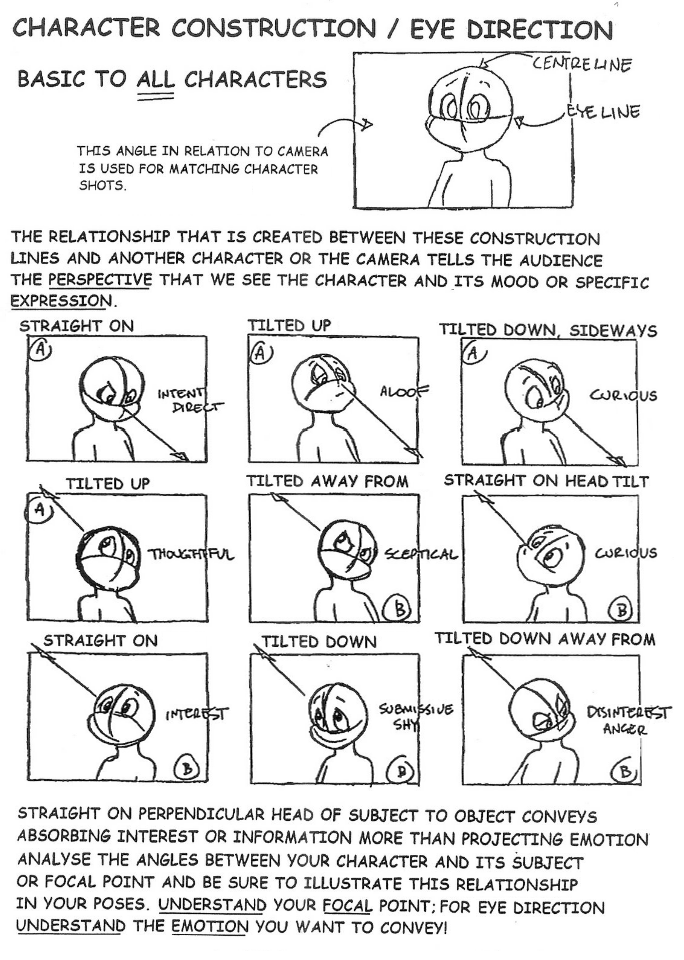

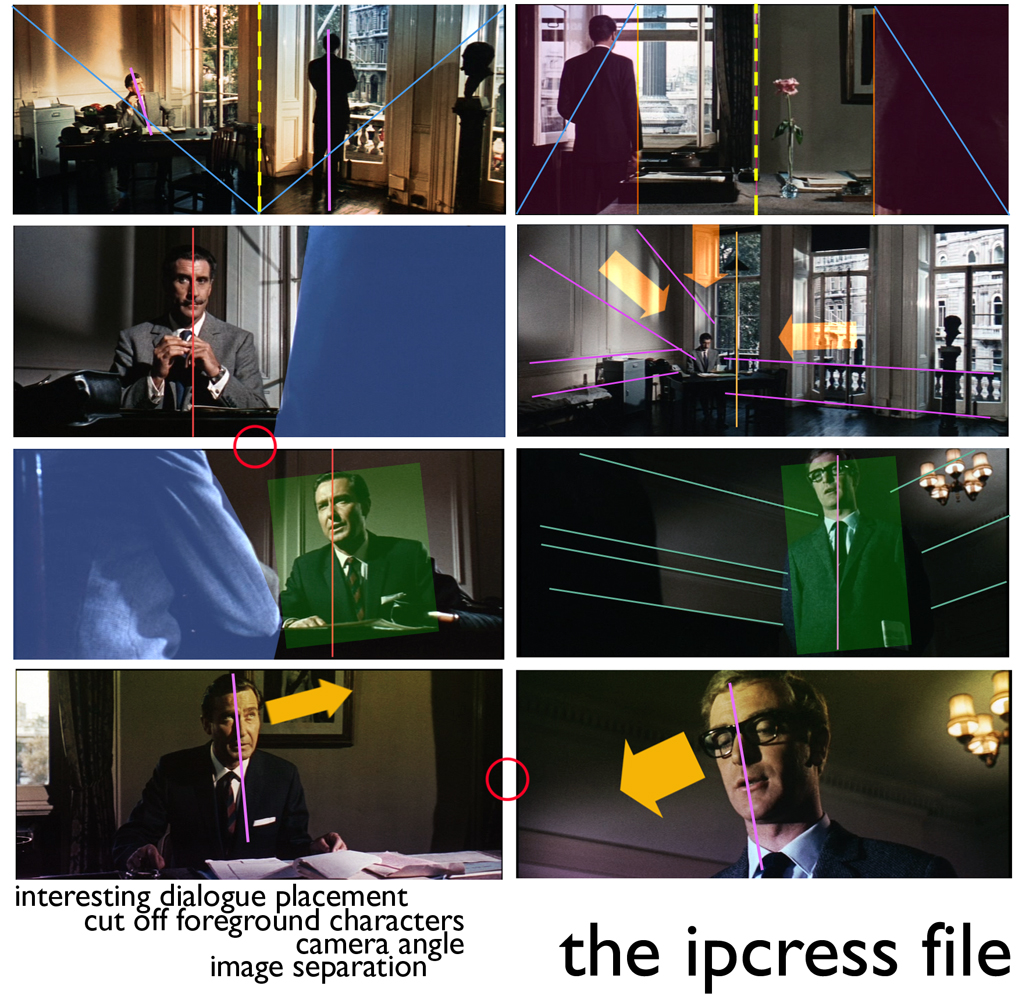

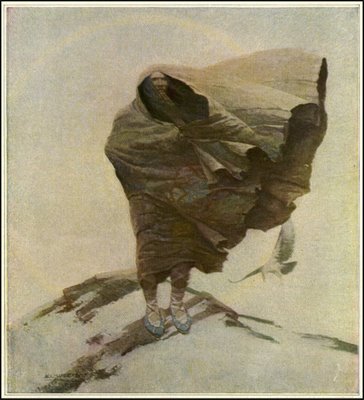

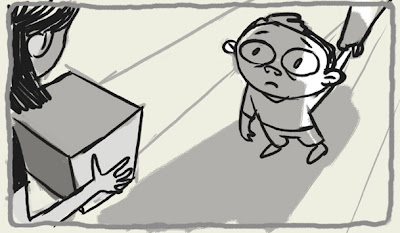

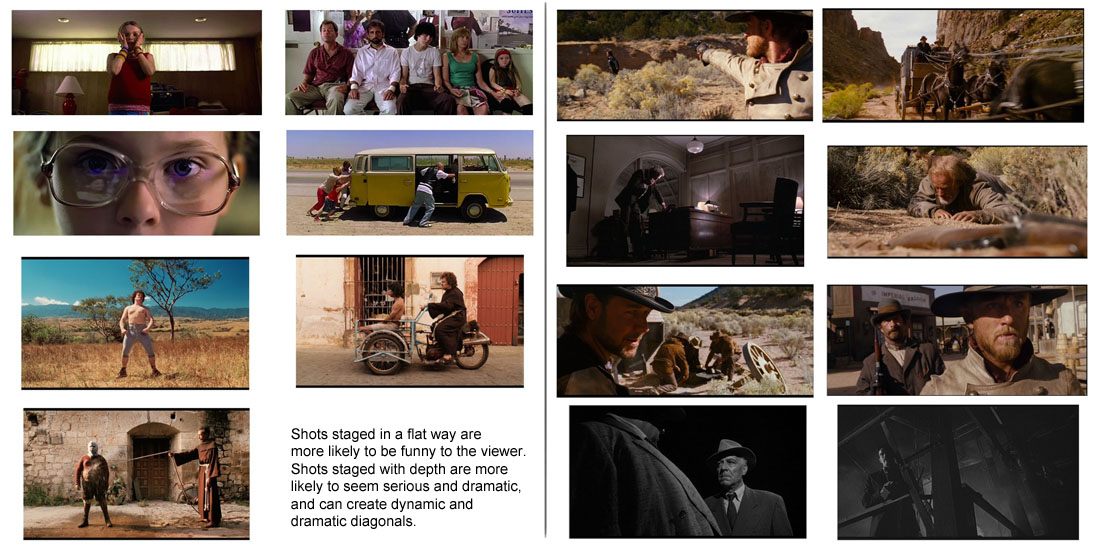

To the right is an alternate staging for the same scene. It gives the boy a chance to act and it's easy to tell right away what the scene is about. I would probably add several panels of acting in this same staging. One of the ways you can change the mood of a scene is simply by changing the angle of the camera. In this post I have presented the same basic scene from 3 slightly different camera angles. I purposefully kept the camera on the same side of the character to help show how the change can effect the feeling of the scene. To begin with I have a level camera to the character. Here you get the feeling the lady is remembering something or someone. A scene like this often is accompanied by a camera move either in or out depending upon the point in the story that it appears. Next I have a low camera angle that give a more heroic or dramatic feeling.

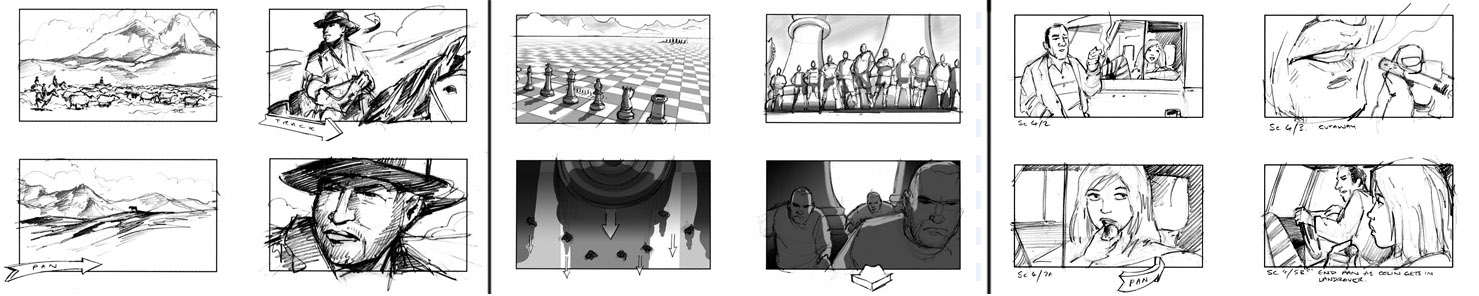

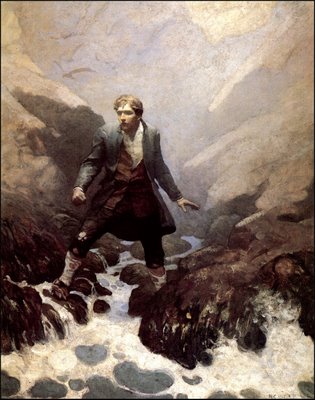

One of the ways you can change the mood of a scene is simply by changing the angle of the camera. In this post I have presented the same basic scene from 3 slightly different camera angles. I purposefully kept the camera on the same side of the character to help show how the change can effect the feeling of the scene. To begin with I have a level camera to the character. Here you get the feeling the lady is remembering something or someone. A scene like this often is accompanied by a camera move either in or out depending upon the point in the story that it appears. Next I have a low camera angle that give a more heroic or dramatic feeling. With this type of camera angle give the character a sense of accomplishment. Either that they will be able to overcome or have already have triumphed. It's basically putting the character on a pedestal. It harkens back to the age of Kings and Queens standing on their balconies looking down upon the peasants. Of course this camera angle can be pushed to the point that a character appears taller than they are. Even old propaganda posters used images of people from low angles. Accompanied with harsh shadows can make it even feel sinister. Often you will see films in which a character that is in a desperate situation use low camera angles with harsh shadows.

With this type of camera angle give the character a sense of accomplishment. Either that they will be able to overcome or have already have triumphed. It's basically putting the character on a pedestal. It harkens back to the age of Kings and Queens standing on their balconies looking down upon the peasants. Of course this camera angle can be pushed to the point that a character appears taller than they are. Even old propaganda posters used images of people from low angles. Accompanied with harsh shadows can make it even feel sinister. Often you will see films in which a character that is in a desperate situation use low camera angles with harsh shadows. The opposite of this is the downshot or high camera angle. It gives a sense of bewilderment or loss. That perhaps the character didn't get what they were after. Like the first example you will often find a shot like this accompanied with a camera move out. It can also be pushed to give a stronger feeling. A downshot also helps to give scale and place the characters into their world. In many live action movies a crane is used to bring the camera to this angle. No matter how you use these angles it's always good to keep in mind that the angle should not feel out of place. I find it is always best for you audience to not be so aware of the camera. This included camera moves.

The opposite of this is the downshot or high camera angle. It gives a sense of bewilderment or loss. That perhaps the character didn't get what they were after. Like the first example you will often find a shot like this accompanied with a camera move out. It can also be pushed to give a stronger feeling. A downshot also helps to give scale and place the characters into their world. In many live action movies a crane is used to bring the camera to this angle. No matter how you use these angles it's always good to keep in mind that the angle should not feel out of place. I find it is always best for you audience to not be so aware of the camera. This included camera moves.

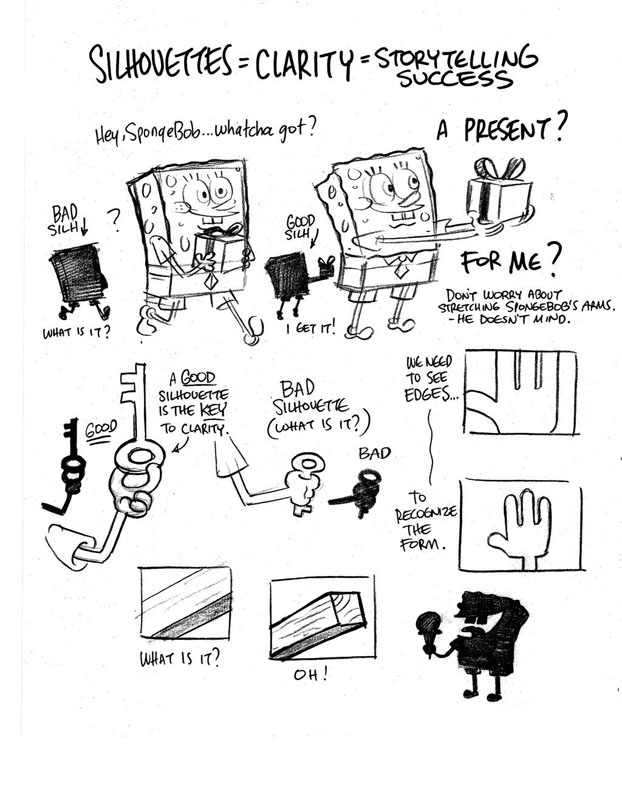

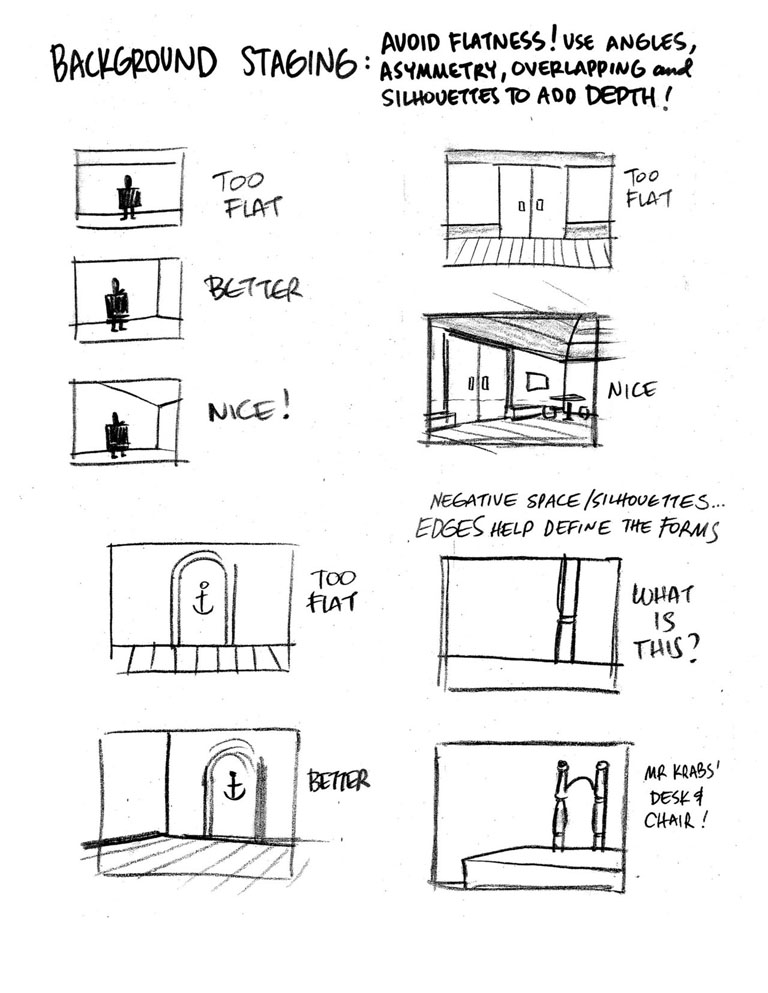

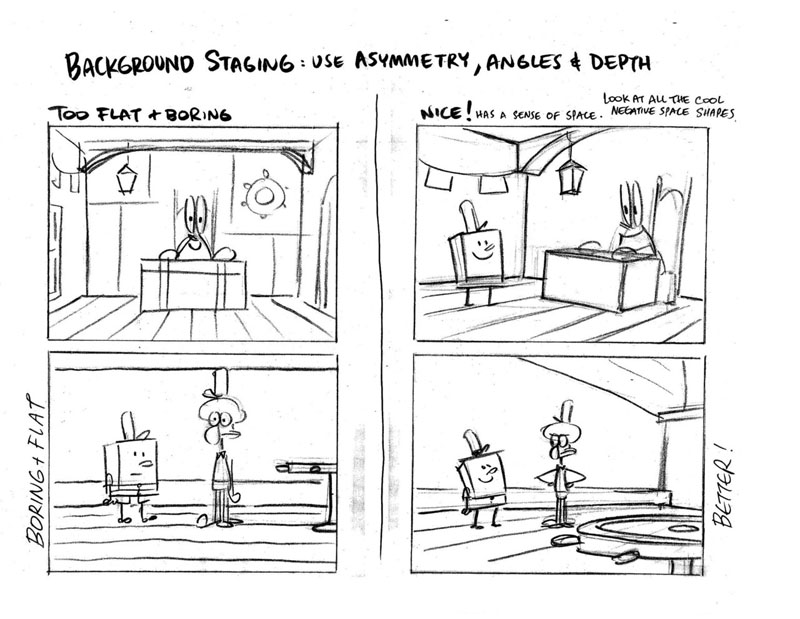

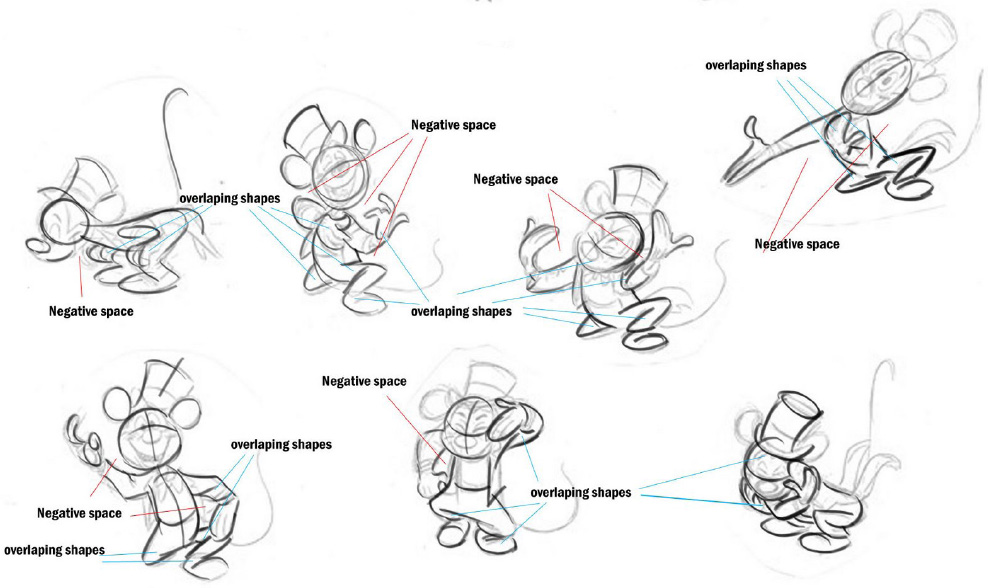

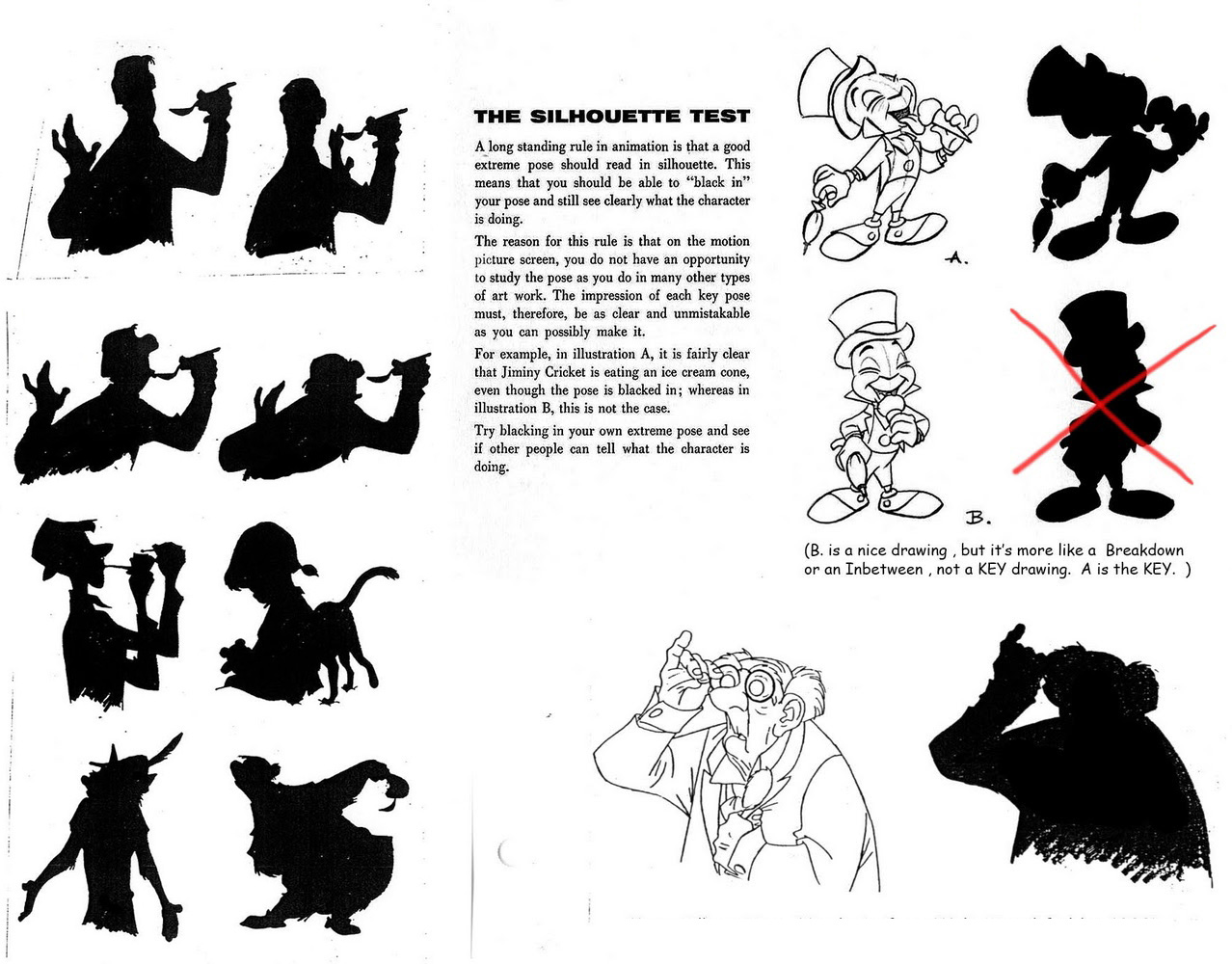

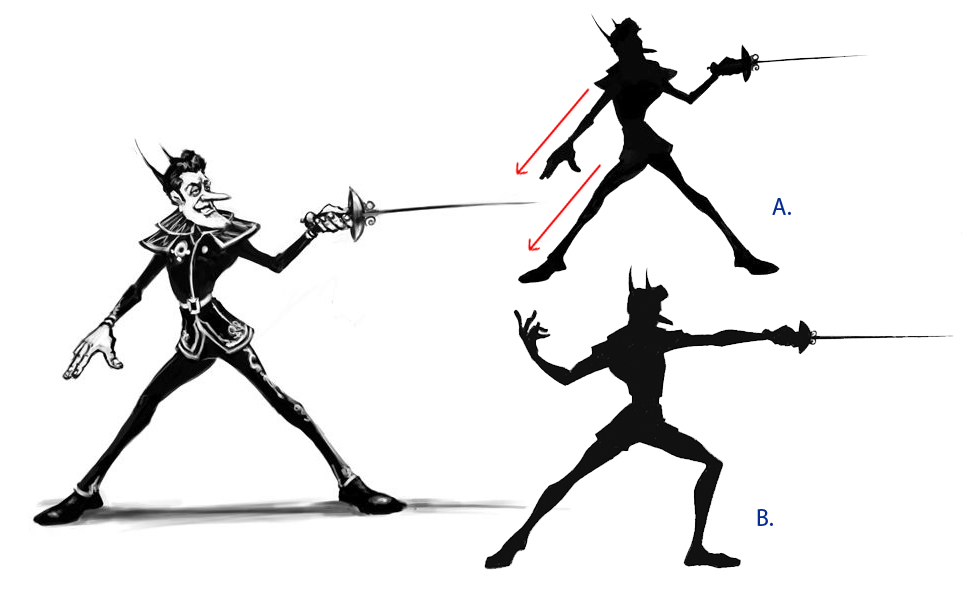

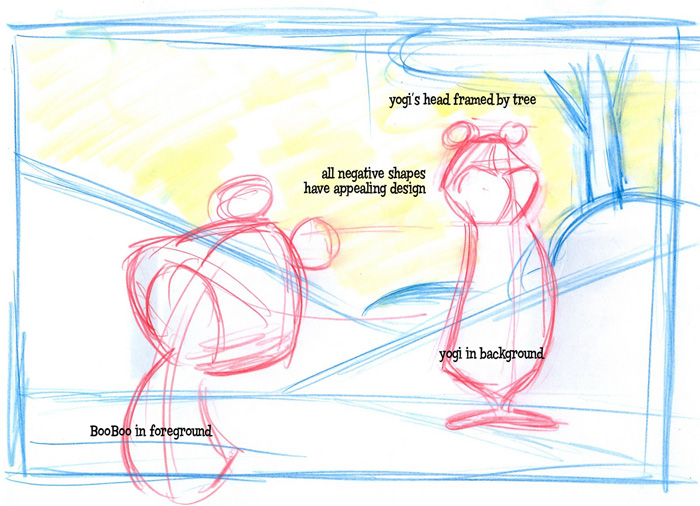

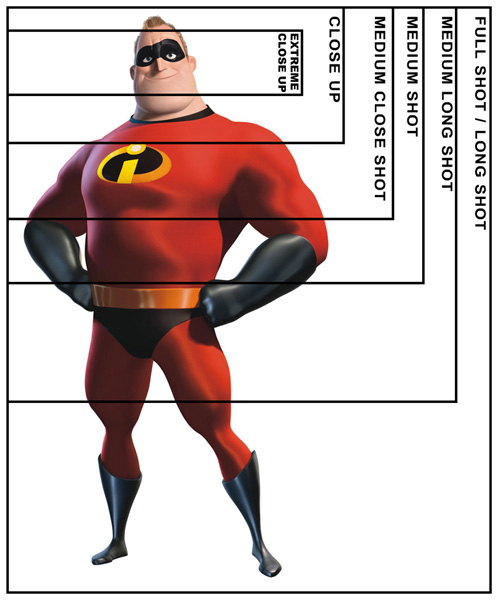

One of the best bits of advice I ever received was, "stage a scene based on the widest action." It's usually not necessary to zoom in super close on the characters... it's nice to leave some breathing room. This allows for nice negative shapes around the characters, and allows you to draw the key players and props with easily-readable silhouettes.

A common mistake of less experienced storyboard artists is framing their shots too tightly. Even a close-up should have a bit of breathing room, unless it is the rare occasion of an extreme close-up.  This also has to do with pacing... it's best to save those high-impact shots were the moments in the story that have the greatest impact. If a storyboard artist were to fill their board from start to finish with lots of crazy angles, fancy camera moves and extreme close-ups, it would leave no room for the artist to show any real impact when it's really needed. It's all about contrast.

This also has to do with pacing... it's best to save those high-impact shots were the moments in the story that have the greatest impact. If a storyboard artist were to fill their board from start to finish with lots of crazy angles, fancy camera moves and extreme close-ups, it would leave no room for the artist to show any real impact when it's really needed. It's all about contrast.

That may mean that the shot is very wide -- for example: if I need to show somebody driving a car around the corner, the shot needs to be wide enough to see all of that action. If I'm trying to show a guy sitting in a restaurant drinking a cup of coffee, I would want the framing to include just the guy, the table, and the cup of coffee.

|

| Cut from Gerald talking on a radio microphone to the broadcast tower, spreading his message across town. |

It's all about how important the specific action is to a scene. If the man at the coffee shop is putting a couple of creams in his coffee, there is no need to make a special emphasis on that action; so I would not cut in closer on him pouring in the cream. But... if somebody was putting poison into his coffee cup, that's a perfect time to cut in on that action for emphasis.

|

| Cut from Grandpa sitting in car to a close-up of him turning on the radio |

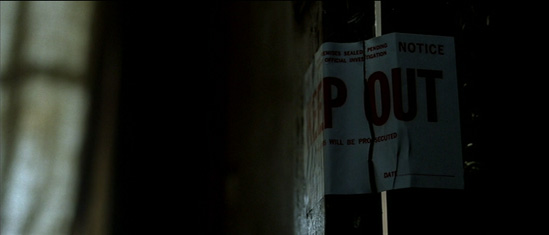

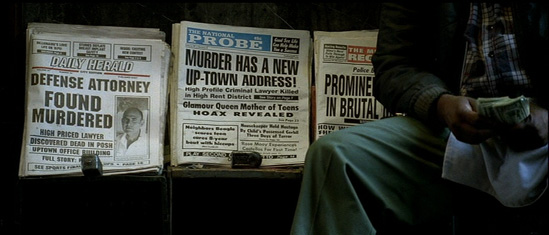

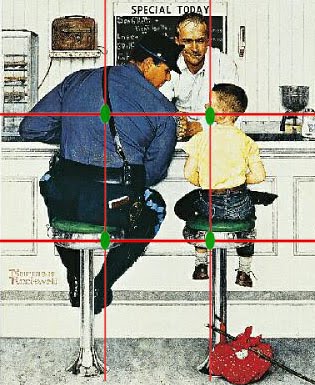

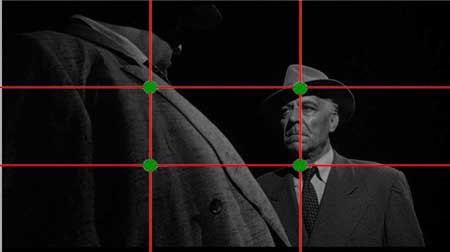

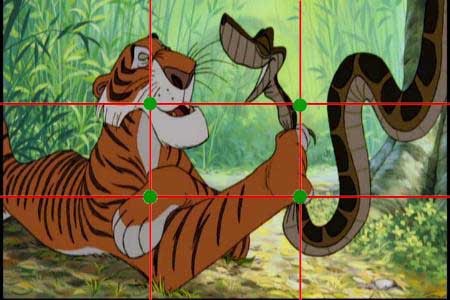

In simple terms, the Rules of Thirds states that there are certain "hotspots" - areas of intensity that exist within any given image, and if one were to align the subject within the range of influence of these hotspots, it will make for a more energetic and interesting composition. The image above illustrates the rule; the 4 "hotspots" where the red lines intersect, and where Morgan Freeman stands. The intensity of the shot is further increased by a small depth of view and the dynamic, diagonal lines that the fluroscent lights form.

Director David Fincher's Se7en ( shot by the brilliant cinematographer Darius Khondji, who also worked on The City of Lost Children, Alien Resurrection, Panic Room, and many more ) is an excellent film to illustrate The Rule of Thirds because of the huge number of still shots that was used in the film. Composition played an enormously important role here in creating tension and interest in the shots when the camera was locked down.

Example 2 : Gwyneth Paltrow lit by a soft rim light and composed within the hotspots. Her frame is supported by the various vertical lines formed by the 2 pillars and the windows in the background.

Example 3 : Brad Pitt framed within the intersecting lines, his pose furthered strengthened by the energetic vertical and horizontal lines formed by his posture.

If chance permits, take a closer look at the film and you will discover that the Rules of Thirds is used again, again and again throughout the entire movie:

Hundreds of other films and television series have been using this principle for decades, always watch for the subject placement in the frame. Of course, I'm not suggesting that if one should start applying the rule that he or she will instantaneous achieve breathtaking, beautiful results; as always it is a case of careful observation as well as a combination of other equally important ingredients like lighting, colour, framing, perspective, space, balance, depth, and leading lines that truly bring out the full effect, no doubt what David Fincher and Darius Khondji did this when shooting Se7en.

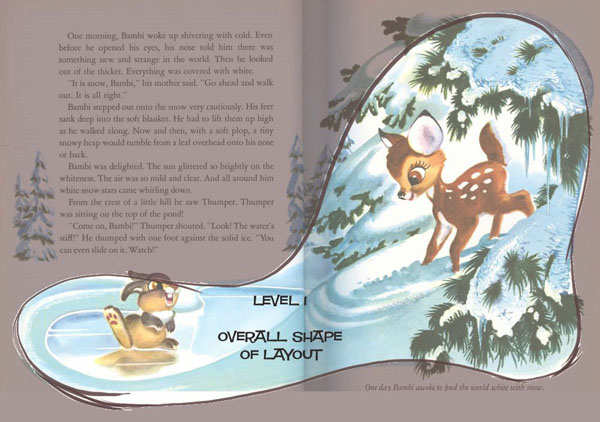

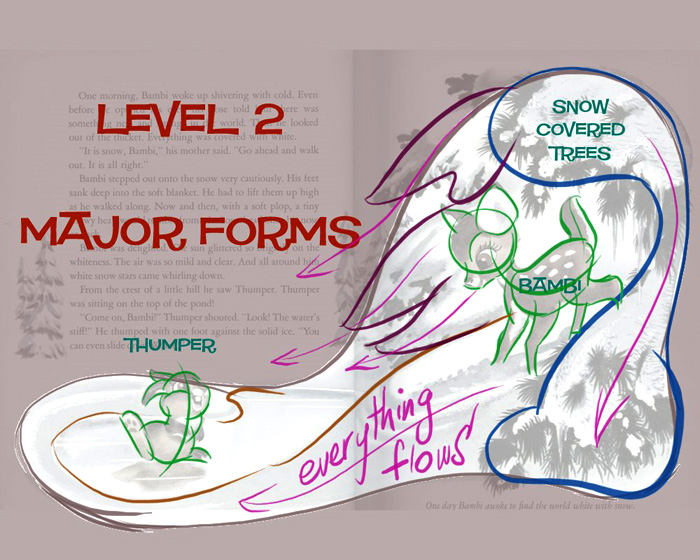

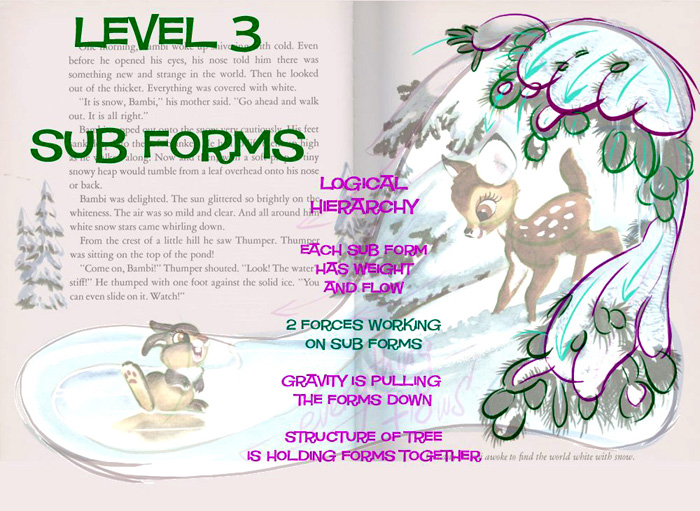

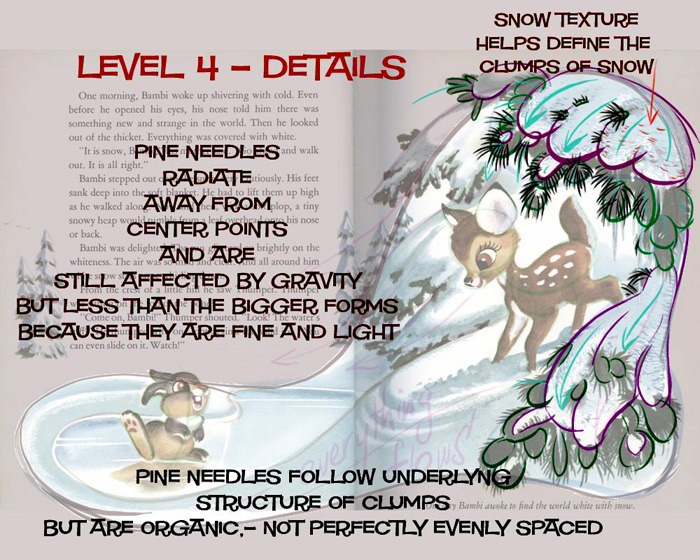

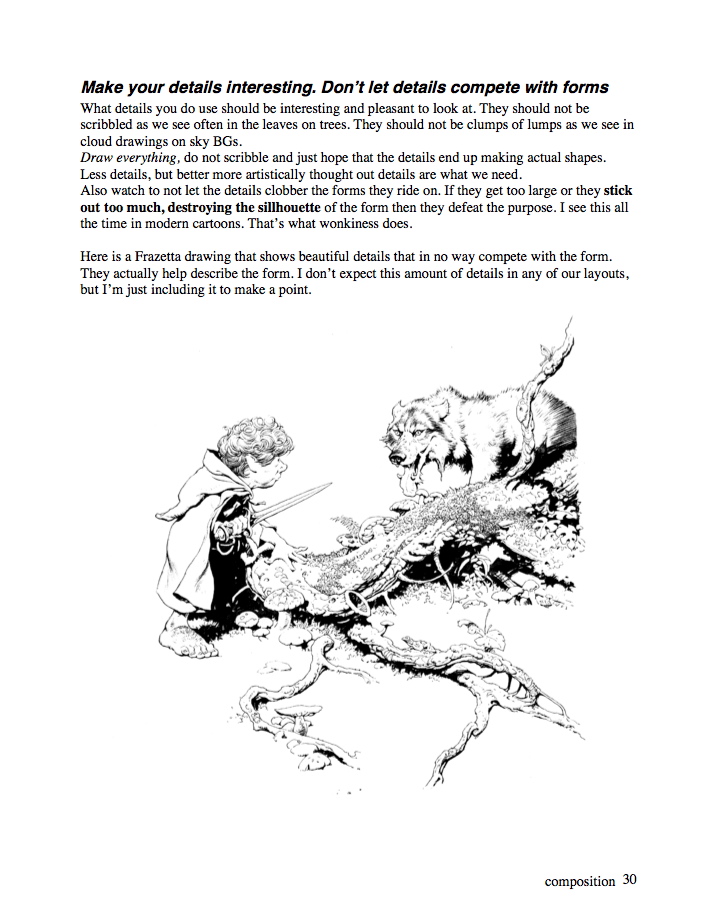

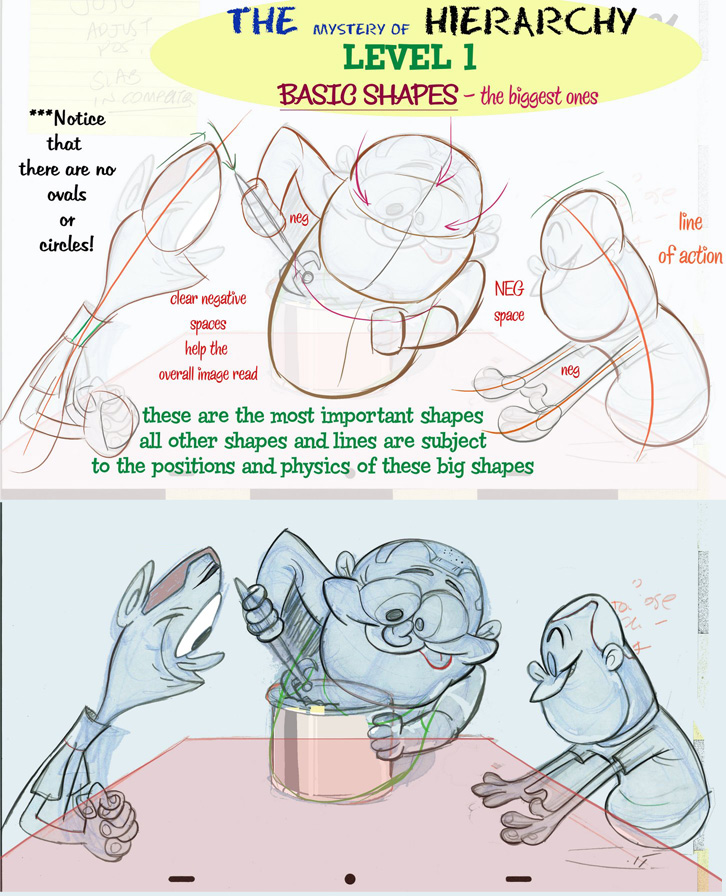

Too many points of interest in one section of your

You

can still see the big shapes dominating the compositions, and the details being

subservient to them through many levels.

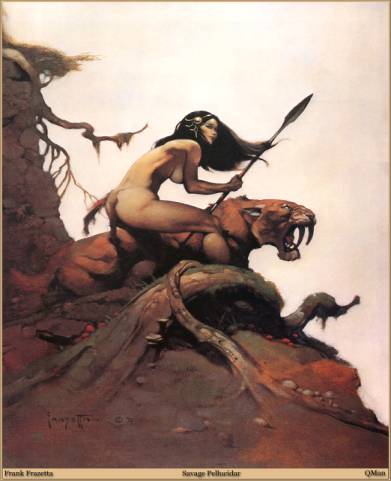

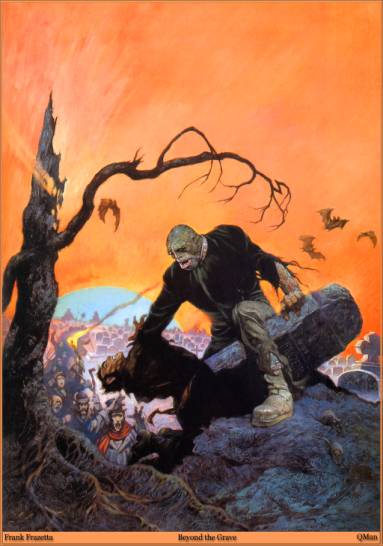

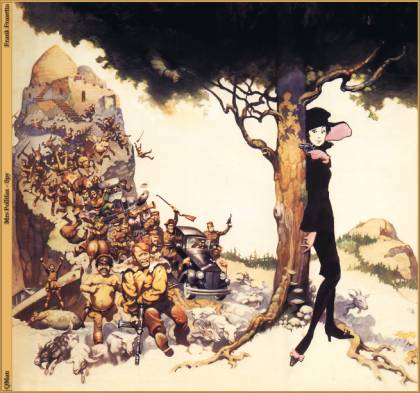

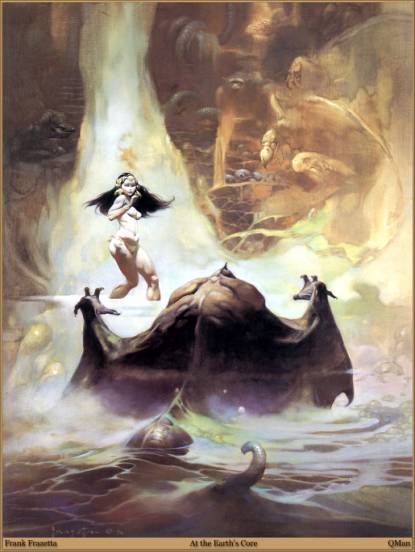

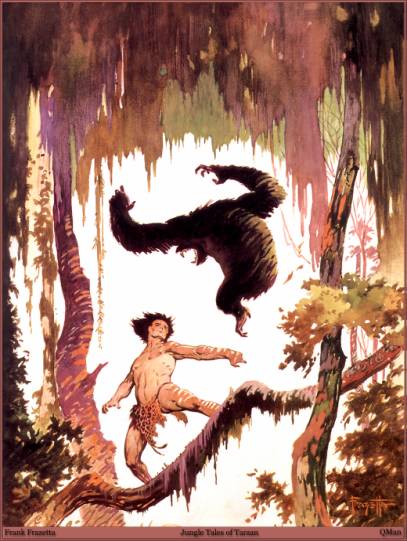

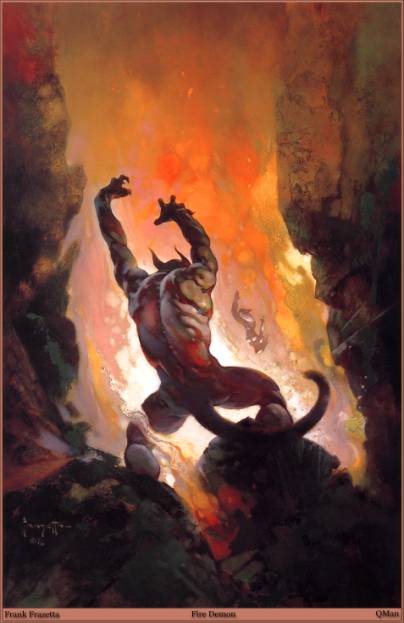

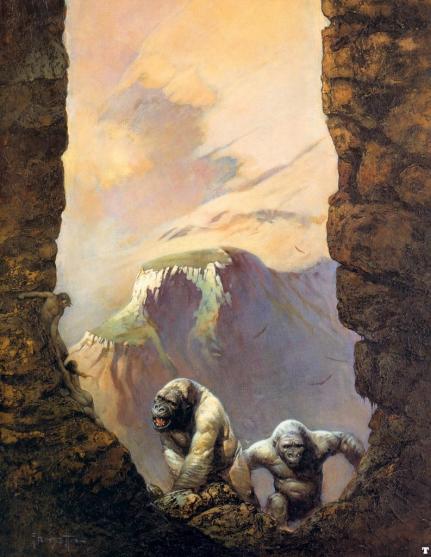

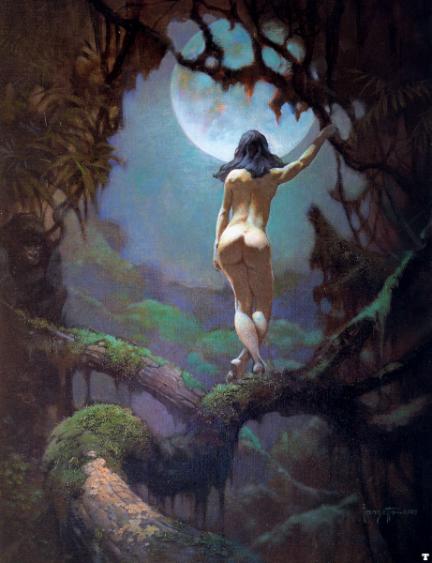

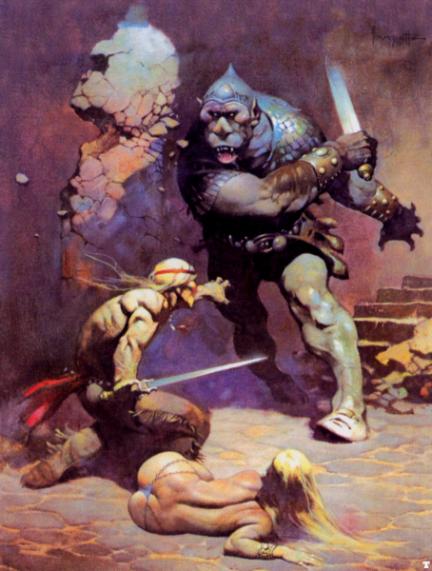

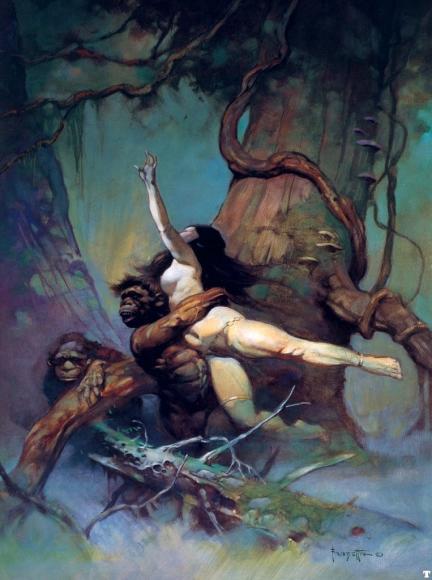

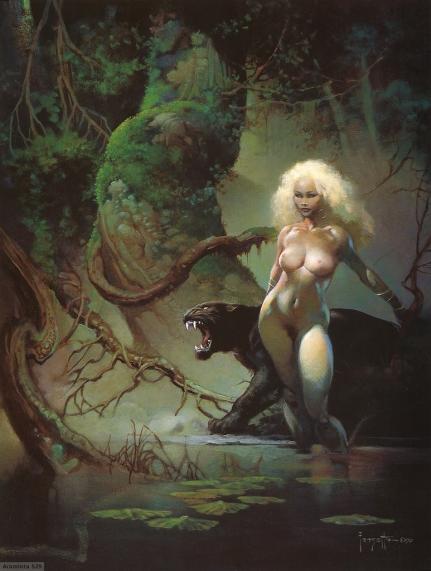

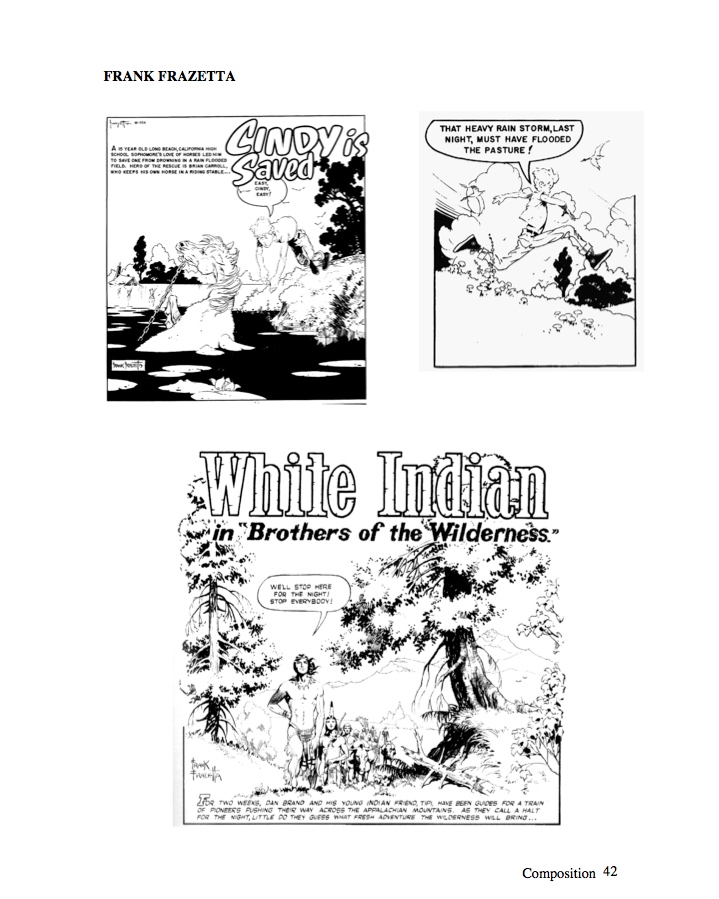

Frank

Frazetta has beautiful intricate details in his work, but his images also are

stunning simple compositions. The whole image is a design. He became a master

at composition and hierarchy - so much so that his work is almost a caricature

of artistic control. Everything in his images fits so perfectly together that

it's almost unnatural - even though he is using guidance from a great

observation of nature.

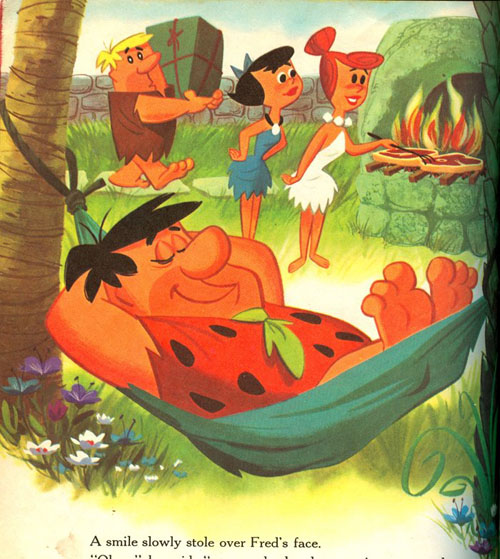

The differences between Frazetta and good animation cartoonists are in individual skill and style, not so much in fundamentals. Frazetta can draw much better than most cartoonists (or anybody else). He also can control more levels of complex detail, and difficult elaborate structures - like anatomy.

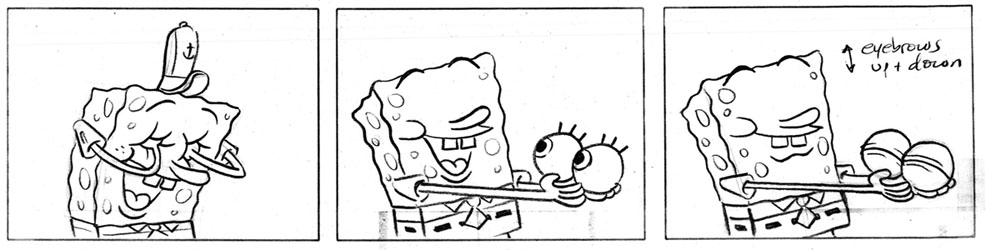

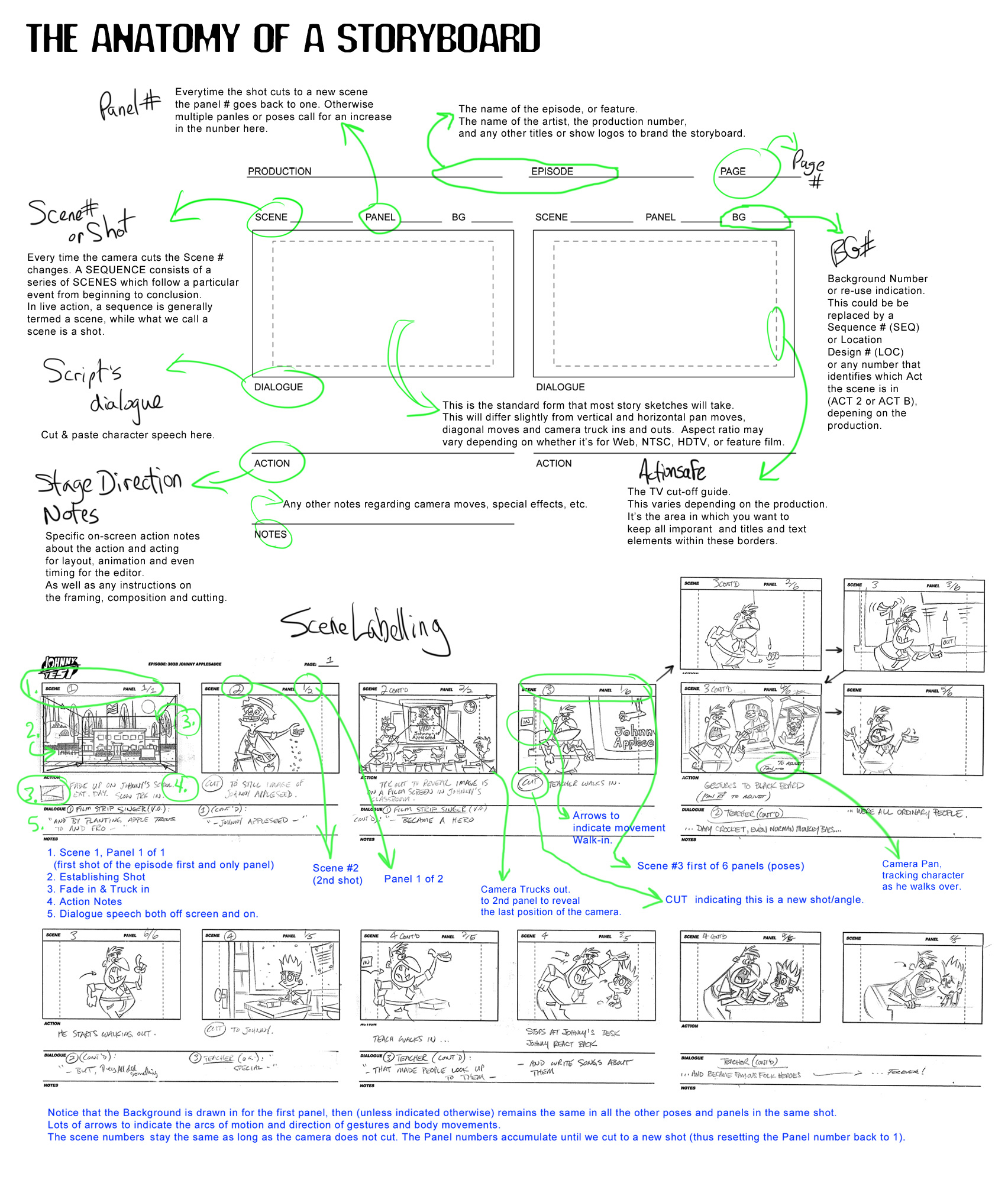

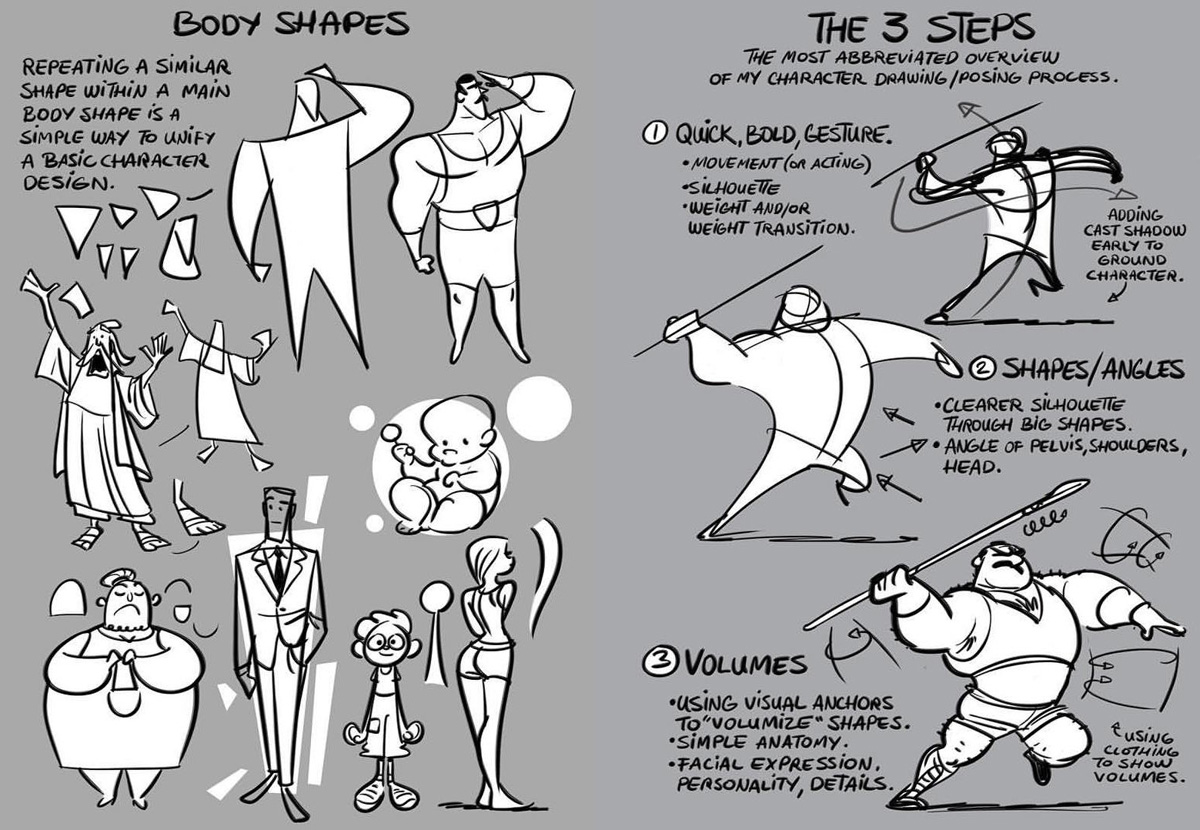

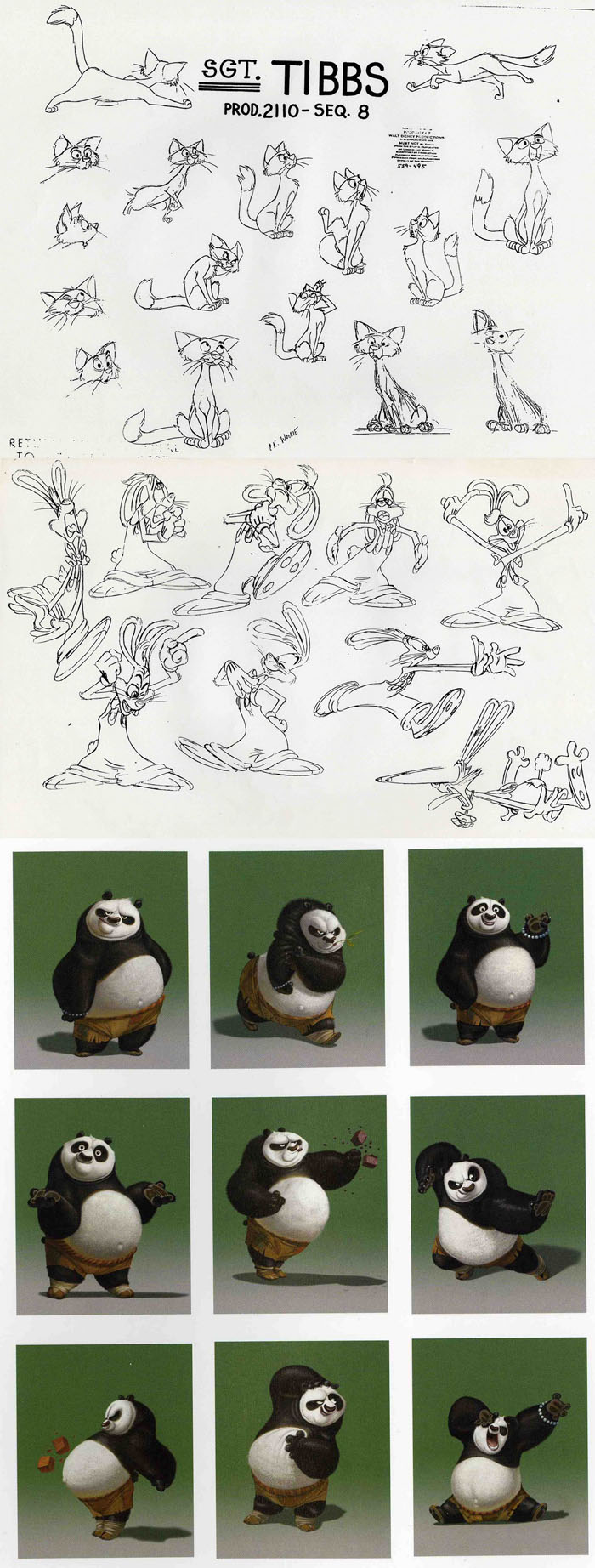

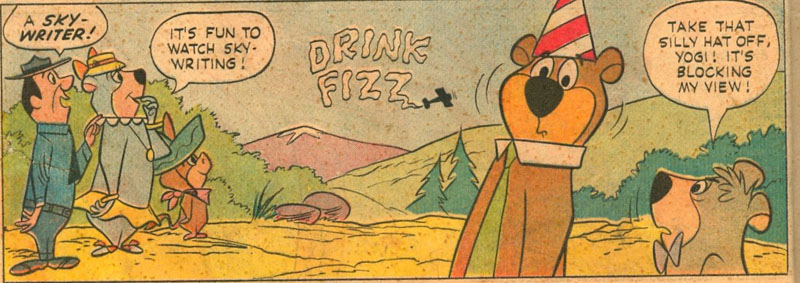

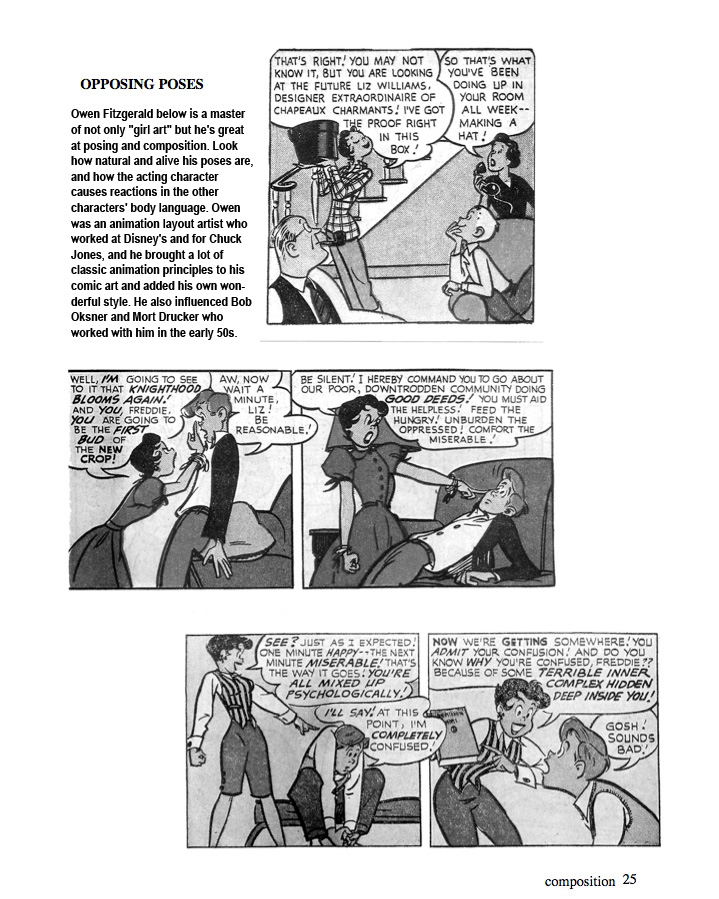

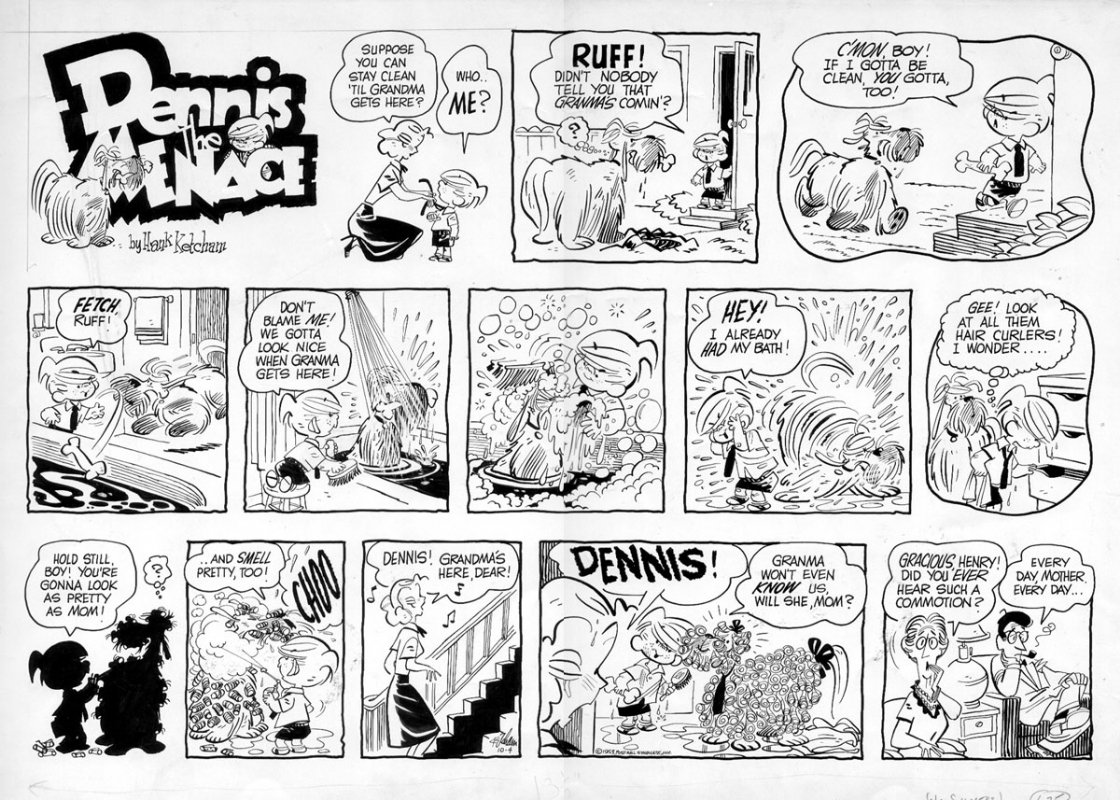

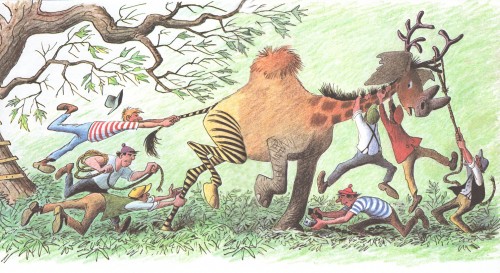

Every character is drawn with a specific expression that reveals their character, and advances the story.

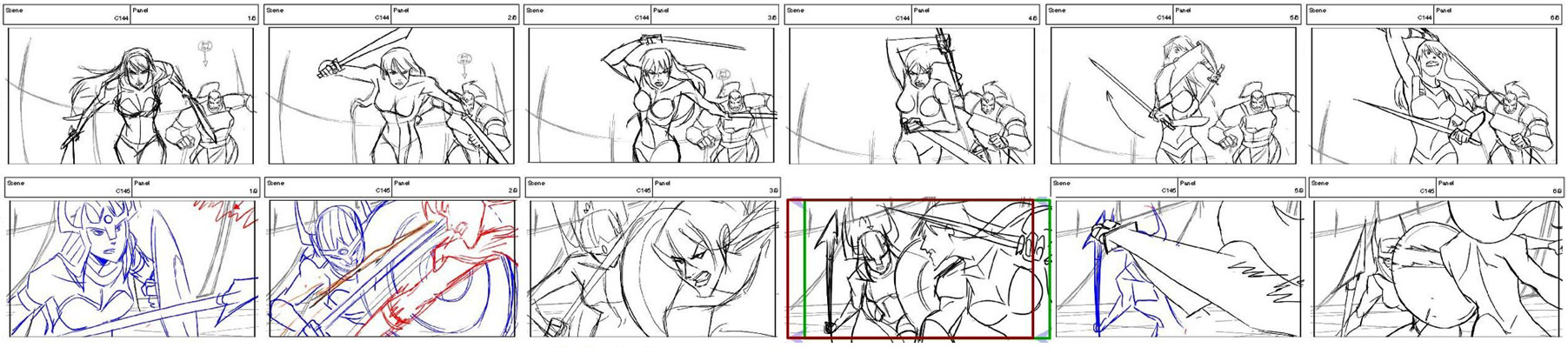

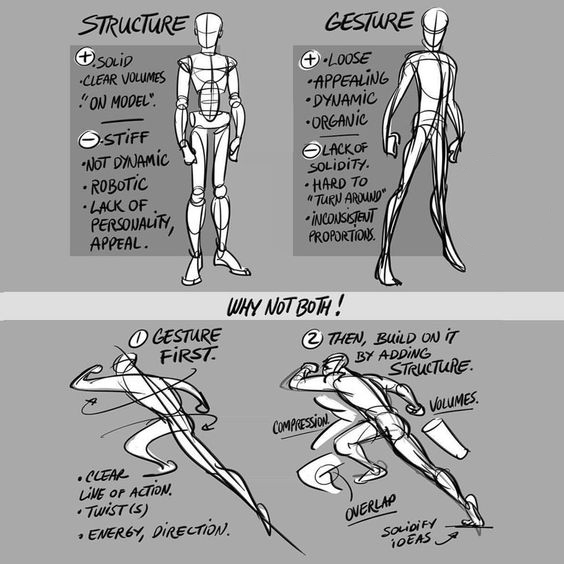

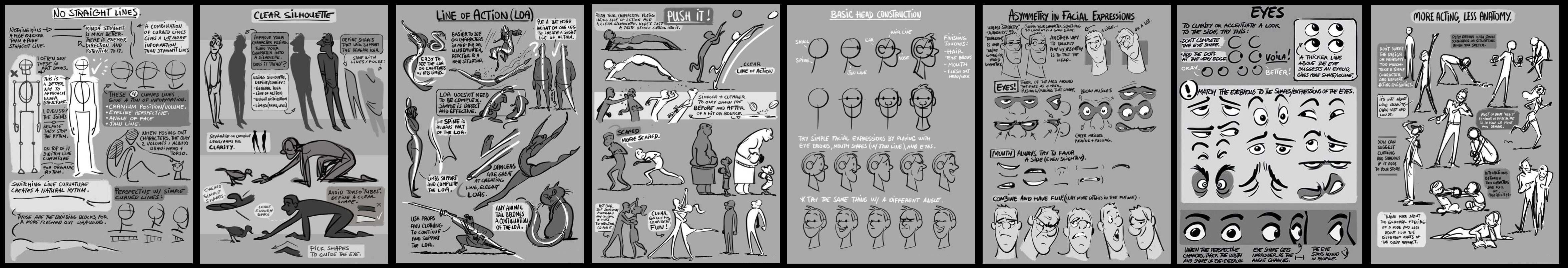

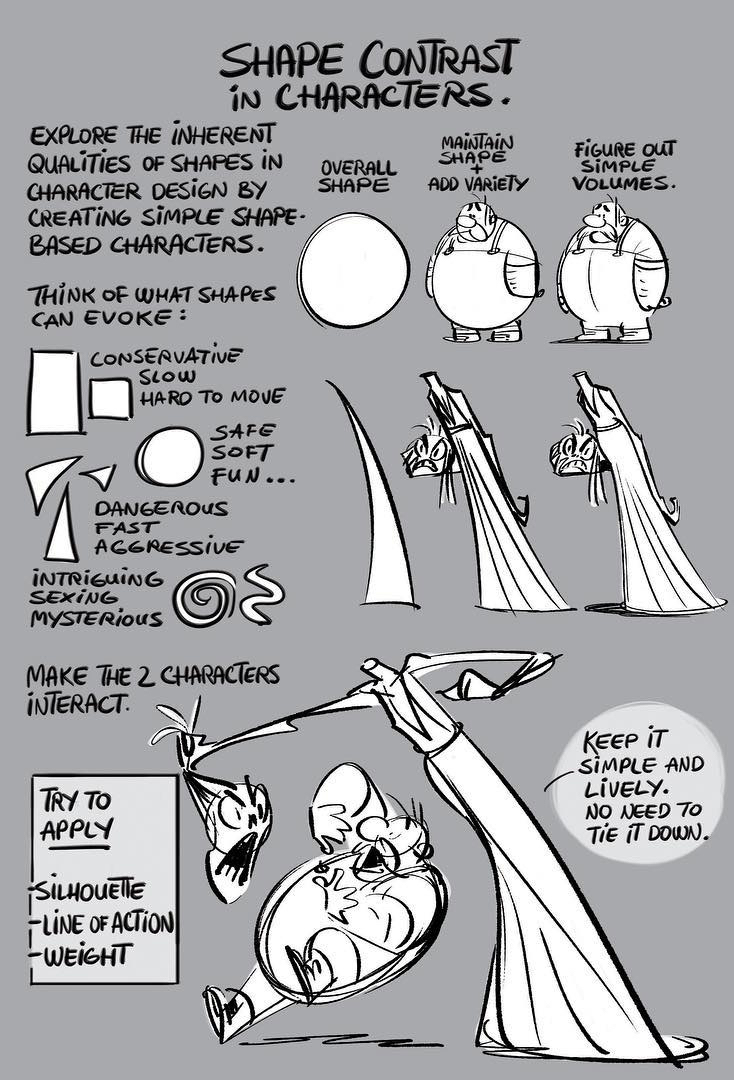

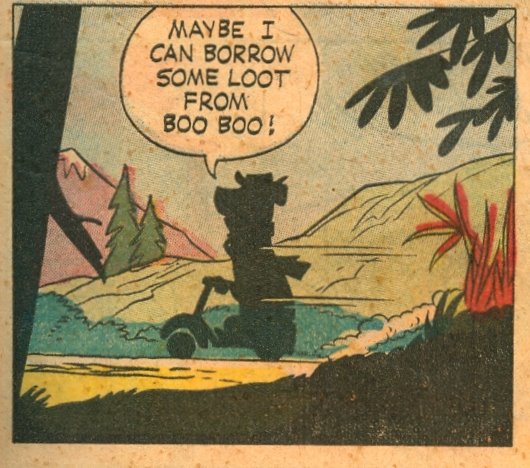

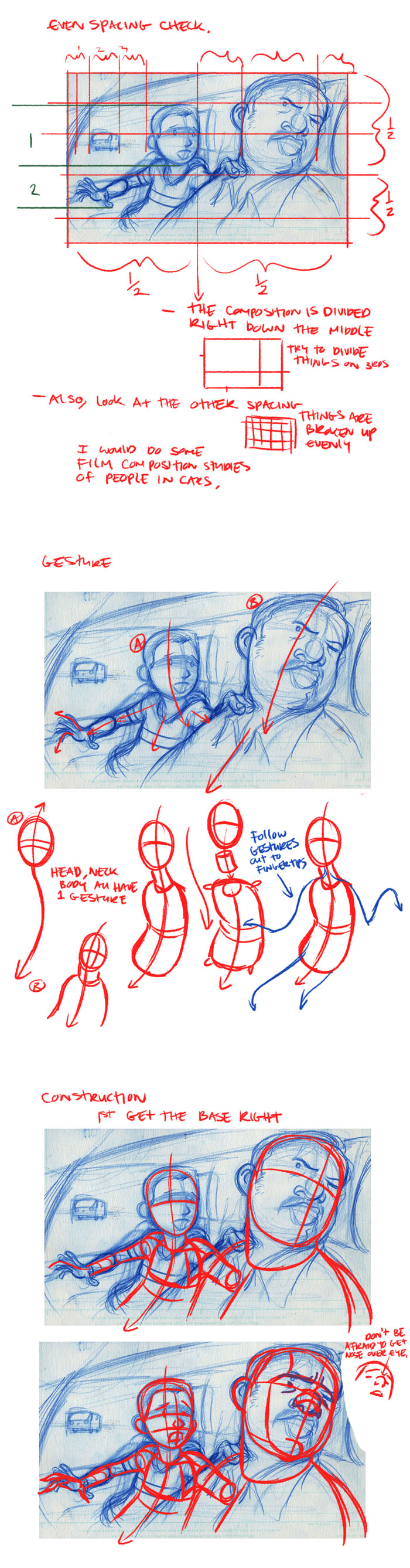

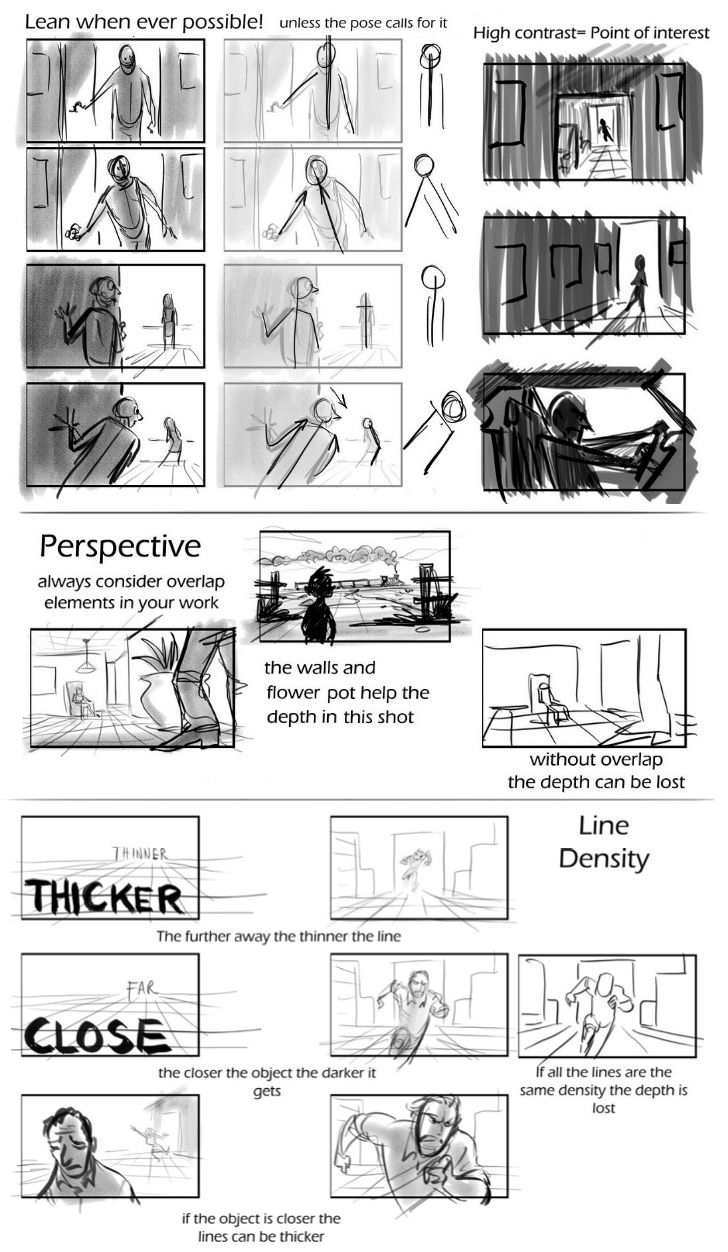

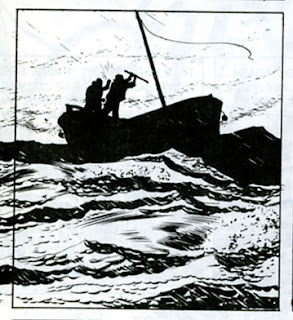

Once you've determined and drawn out the 'content' of your shot; the angle, the framing, the placement of all things - make a quick check for three things that will help the quality of your posing and positioning of your characters: Spacing - Gesture - Construction Contrast is useful in all aspects of your work, but when it comes to storyboarding it shines brighter than ever. Storyboarding is all about telling a story with one image and leading the viewer's eye to exactly what's important. It is normally just one part of a sequence, but an essential bit that the viewer absolutely needs to see in order to fully grasp the story being told. It may linger for a split second or much longer, depending on where in the story a certain board falls. Here then contrast through simple tone can do wonders. It can transform a line drawing with a lot going on into a simple composition that everyone knows the focus of instantly. Take a look at this amazing storyboard panel by Michael Lester who works over at Dreamworks: There's a HUGE amount going on in this subway car, with a large cast of characters, but thanks to tone and contrast your eyes are drawn immediately to the most important aspect (the dog in the hat) and then allowed the freedom to look over all the happy riders around him. The darker tone for the dog also plays nicely into the sad pose he's taking. (Truth be told we could study this image all day for a treasure trove of artistic goodness, but let's get back on topic for now.) Behold, like a magic trick, what happens when we remove the simple tonal contrast! Suddenly you notice a whole lot more lines than the partially filled piece. Where exactly are you supposed to look? Is the focus the large cat to the left? Perhaps the laughing character? Maybe the story is following the child to the right, off on his first subway ride? Eventually you might make note that the dog character has a nice aura of negative space (not touching any other characters) so it may be the story is about him. Without the tone, though, getting to that point takes a lot of thinking and a long time. Time storyboard artists need to keep moving along quickly. If you'd like to see more examples of superb use of tone and contrast in storyboards, Michael's blog Ninjerktsu does not disappoint. It's filled with storyboard-like-comics that are as hilarious as they are beautiful. (This one about a “Cat Lady” is one of my personal favorites.) While it helps to use tone as shadow, you don't need to know advanced lighting techniques to add this aspect to your drawings. Simple blocking of three or four tones is enough to do the trick. Things you want to draw the eye to should have the highest level of contrast, while the areas that you'd like to fade into the background should blend in with less contrast. As an exercise, try adding in these five tones to a line drawing you've done (or add them to another artist's line drawings just to practice).

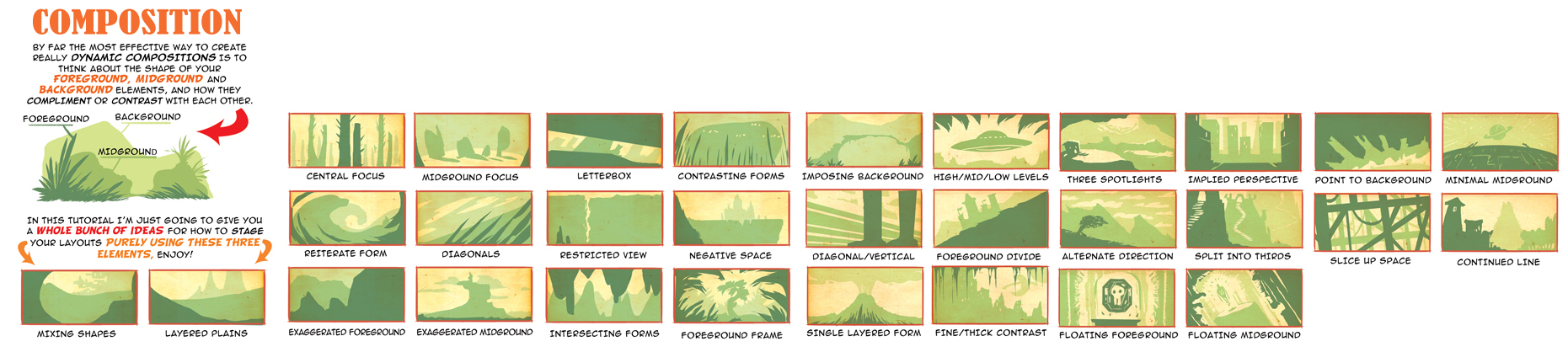

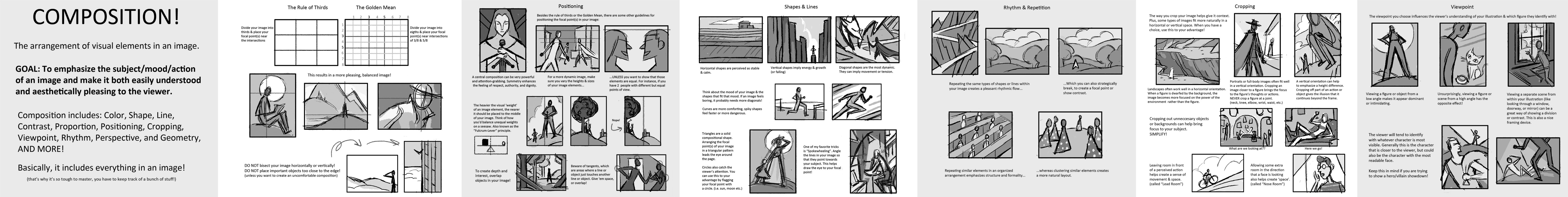

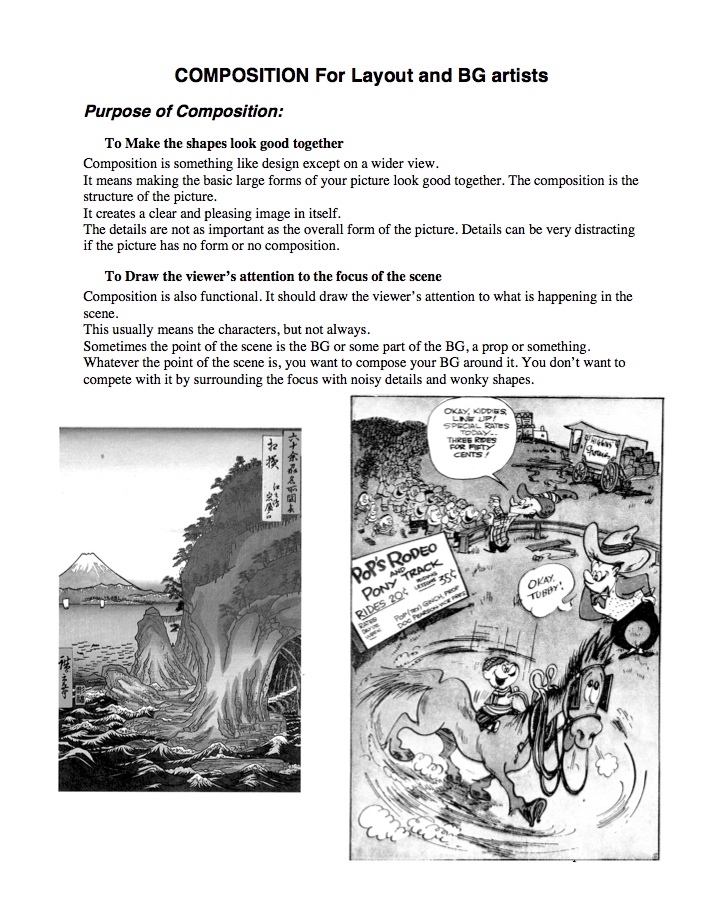

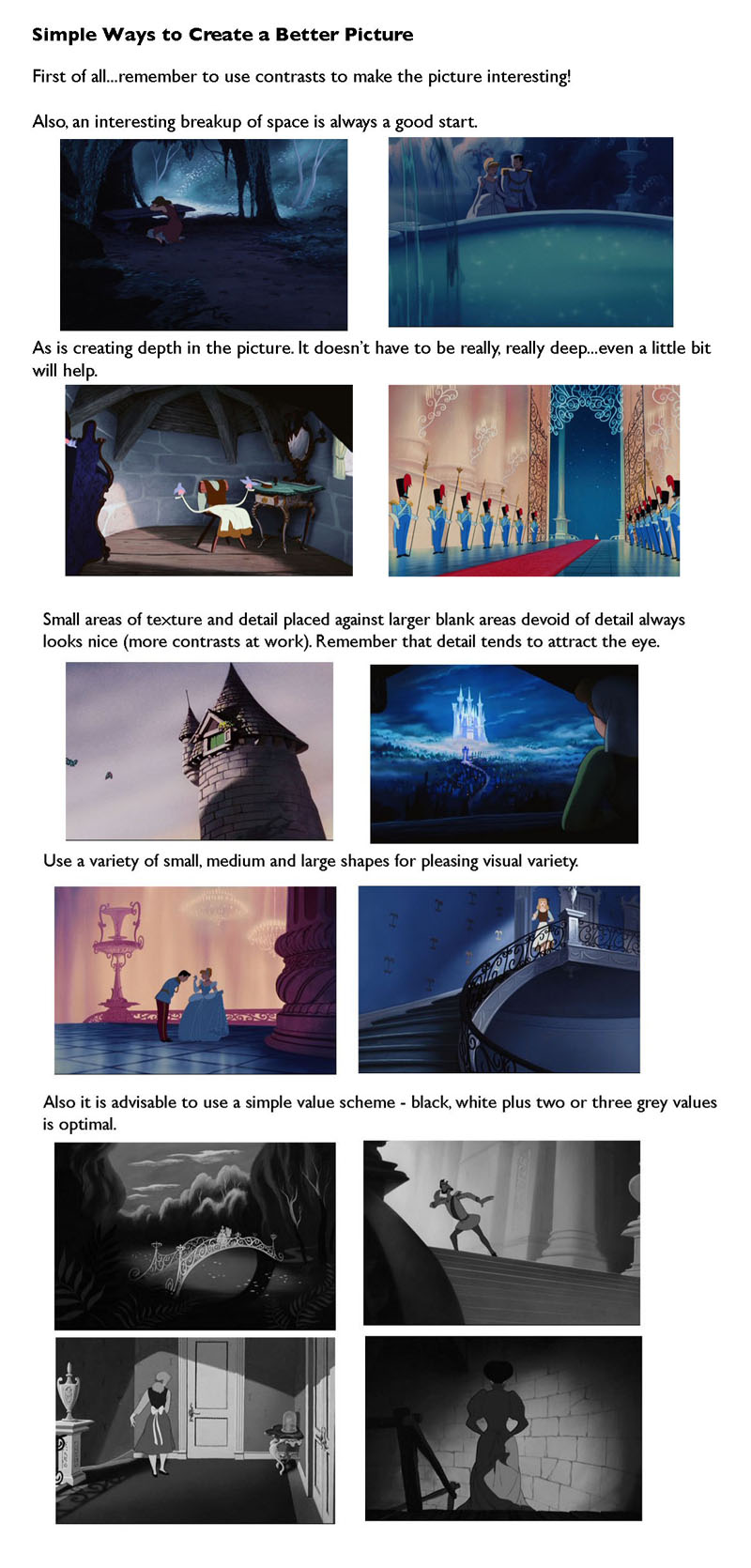

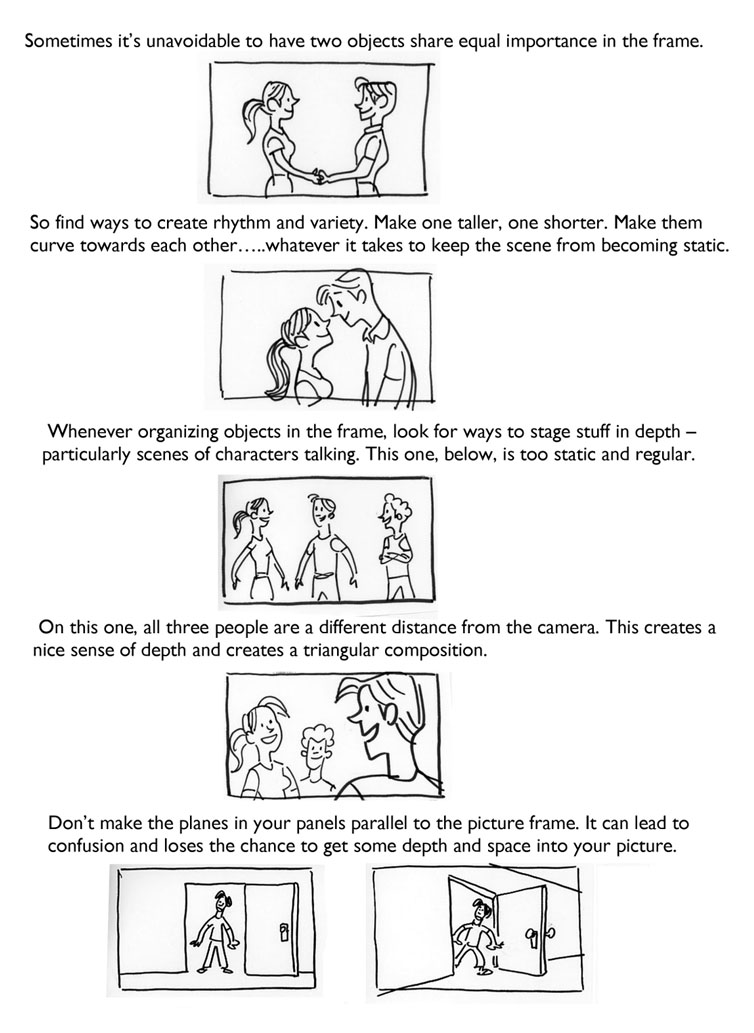

When planning your shots, remember the fundamentals of composition:

Basic Shapes

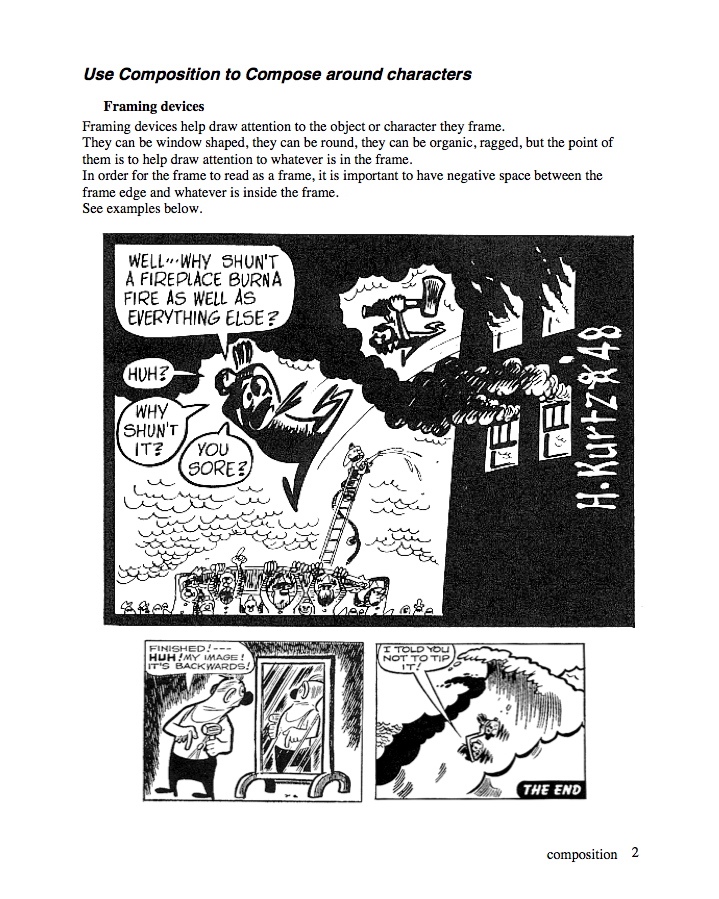

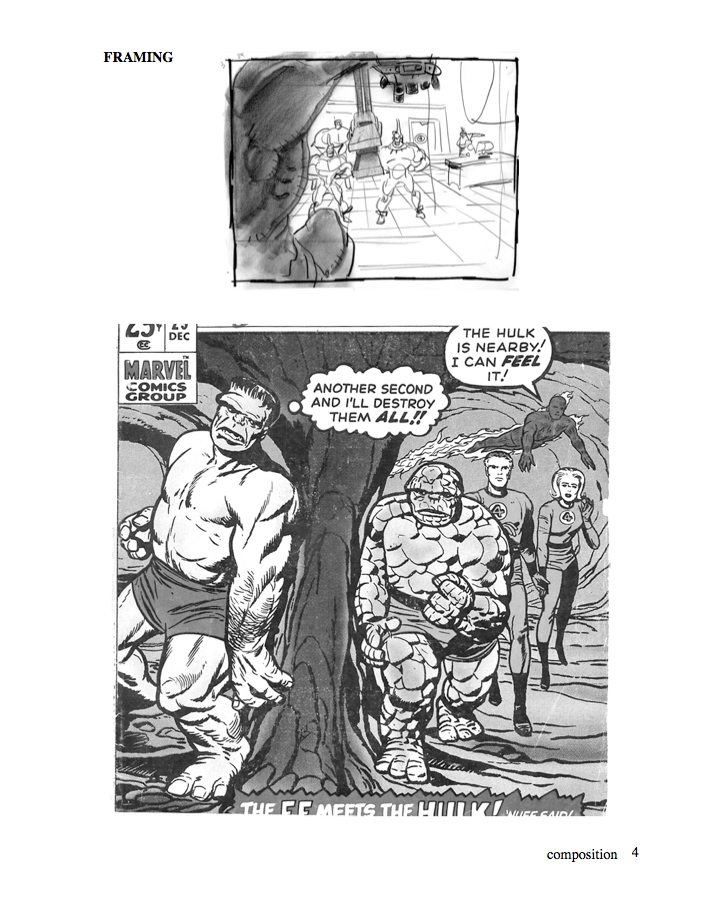

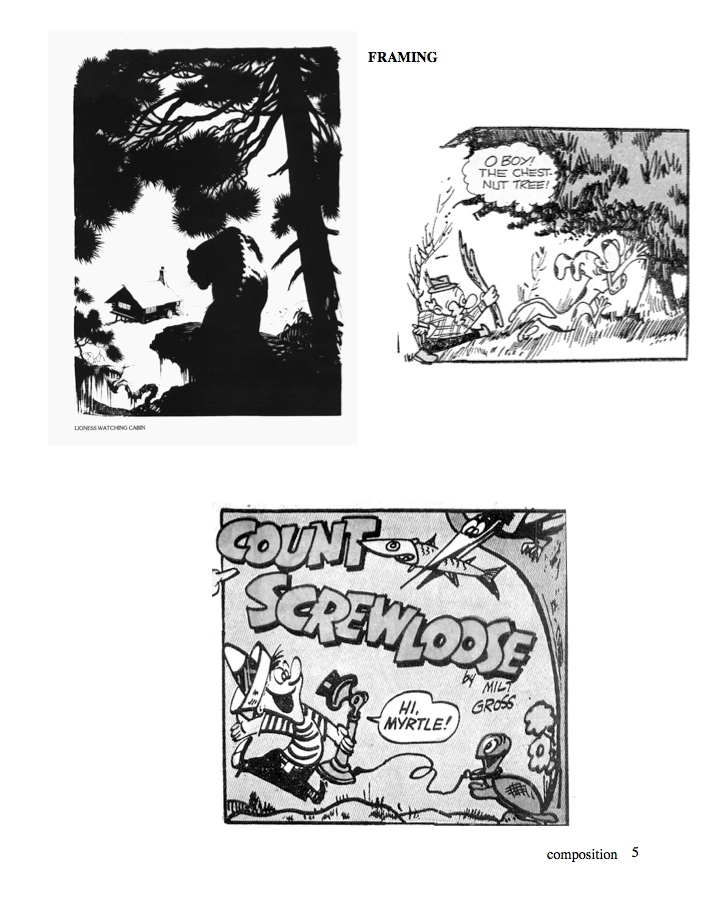

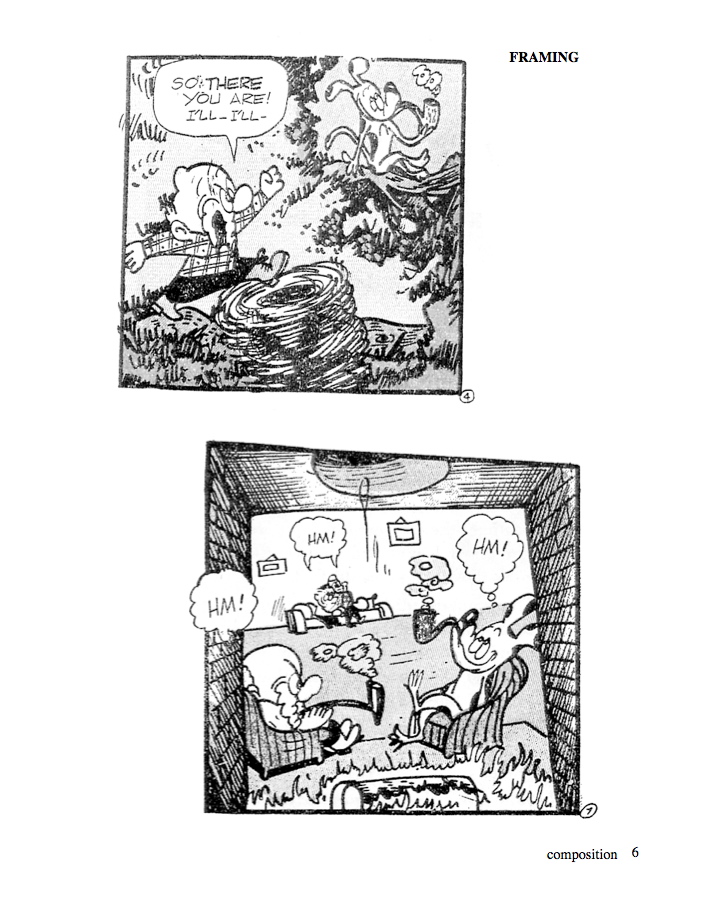

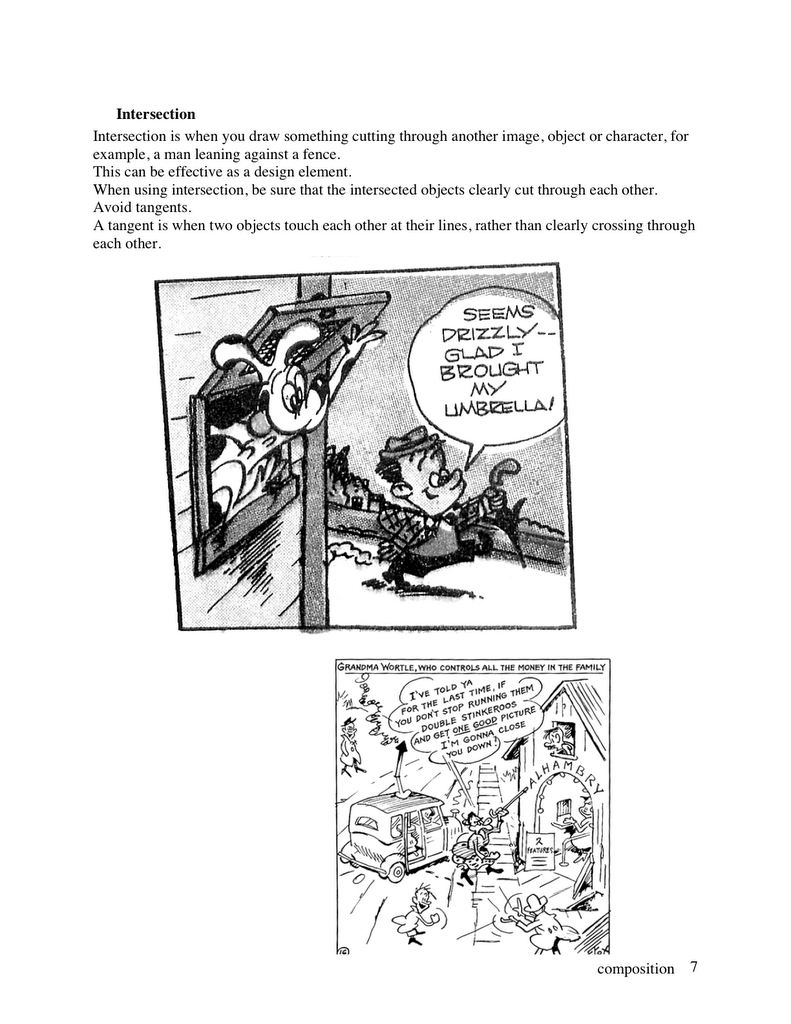

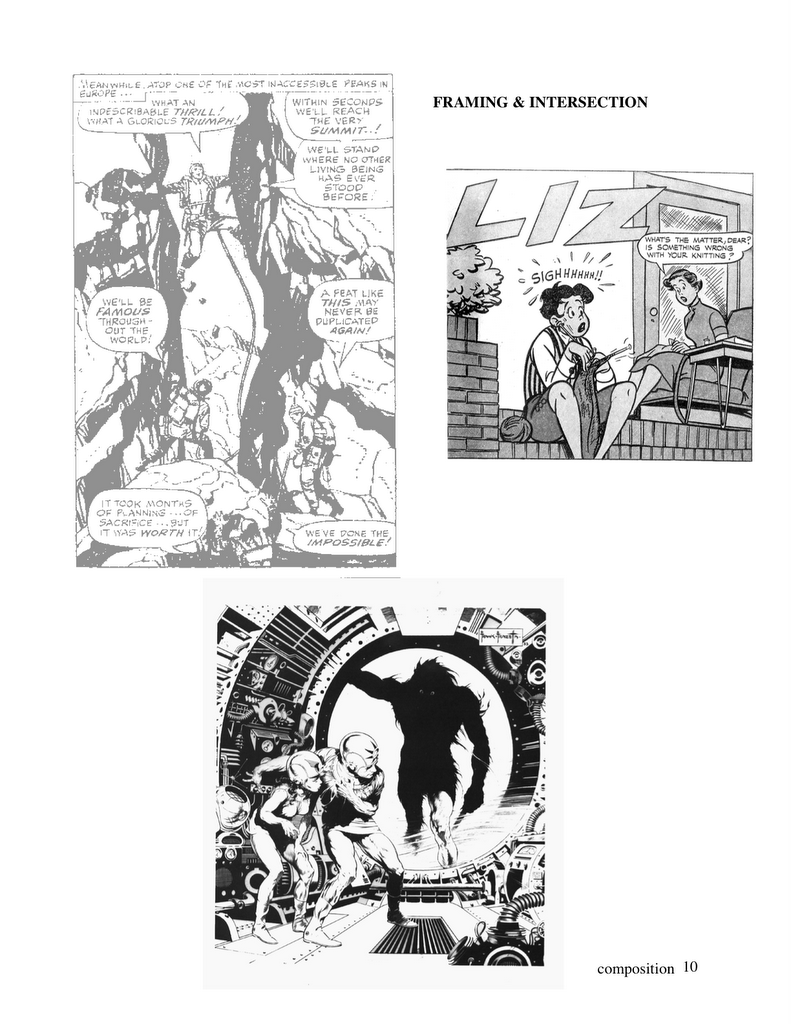

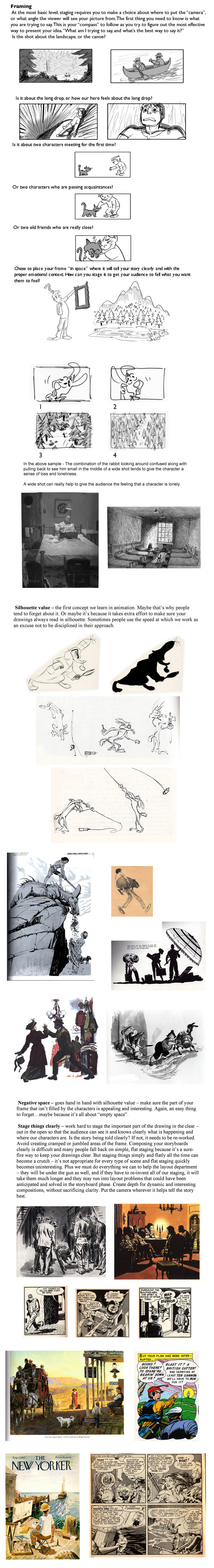

Framing

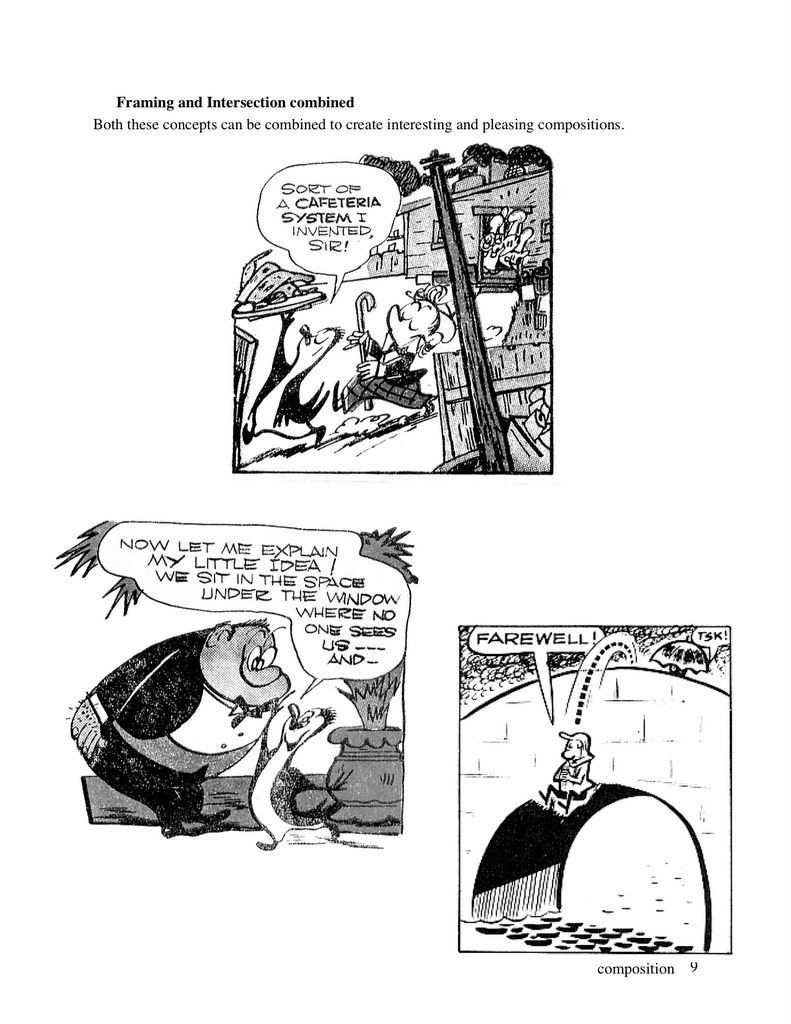

Overlapping Forms

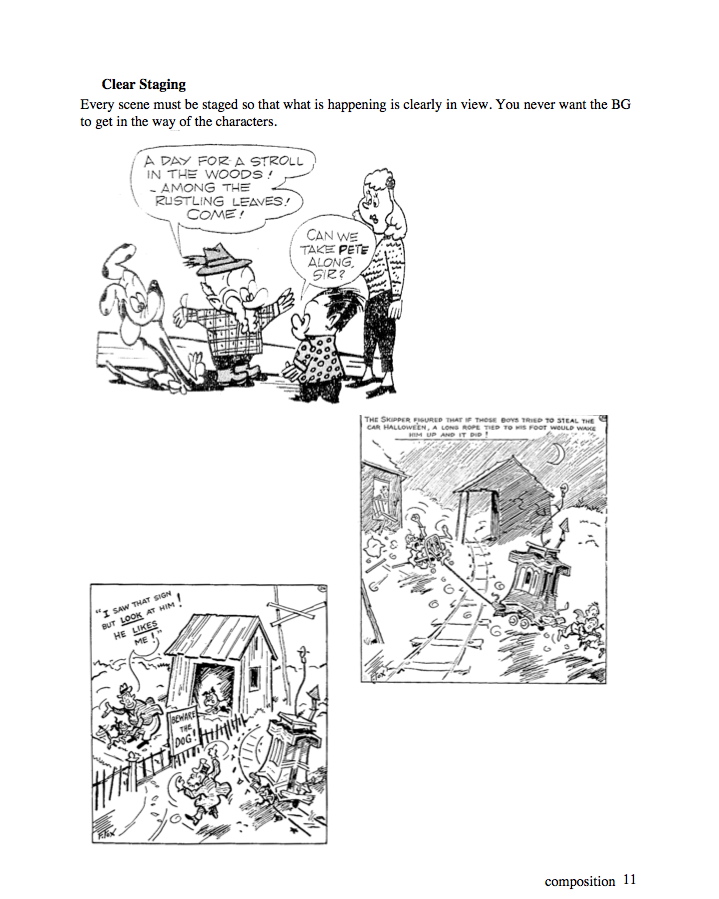

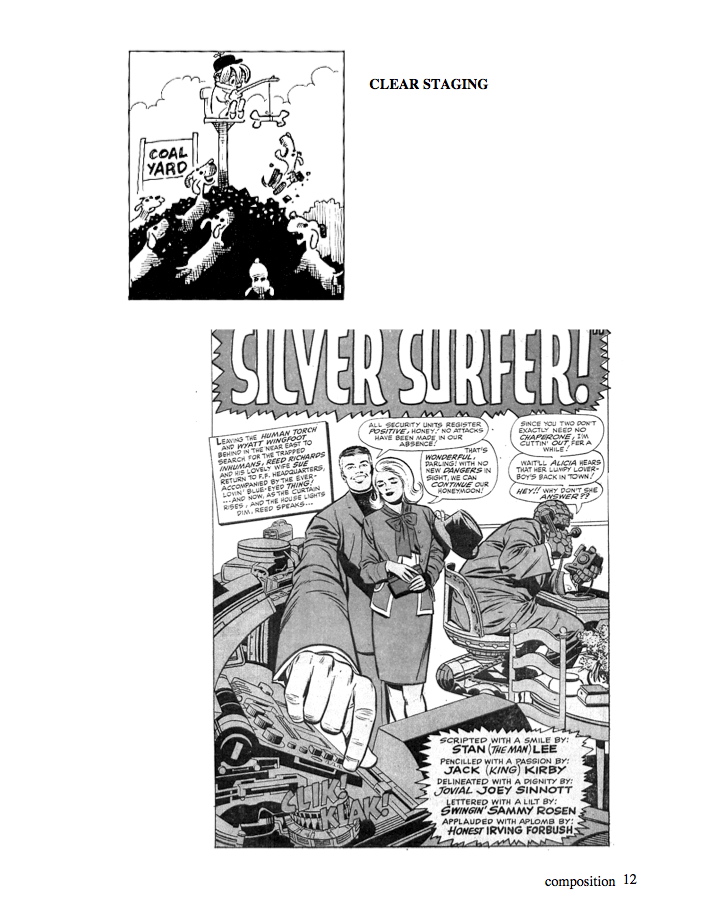

Clear Staging

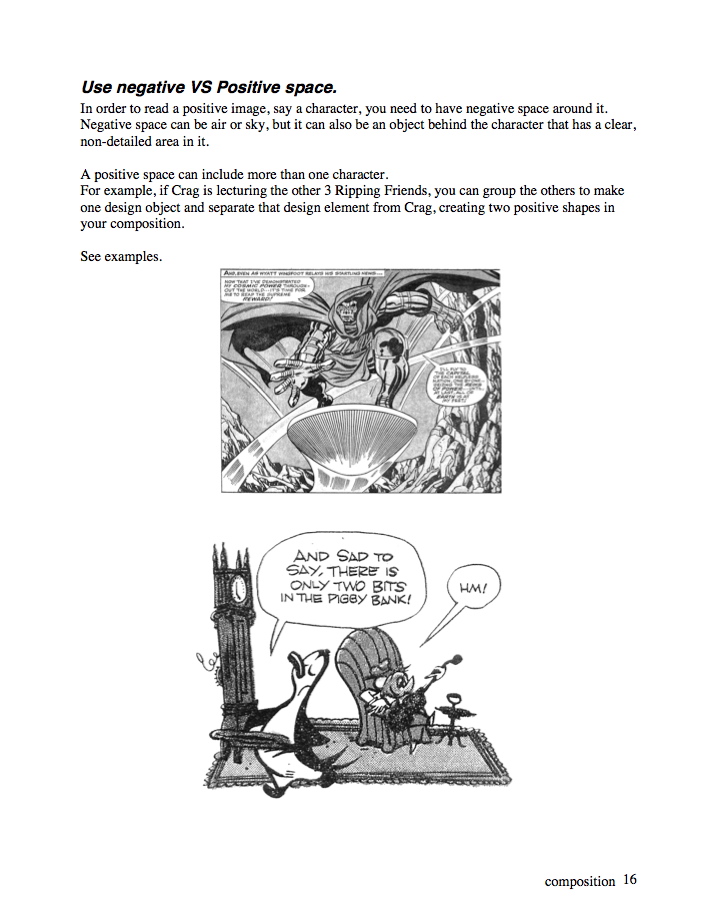

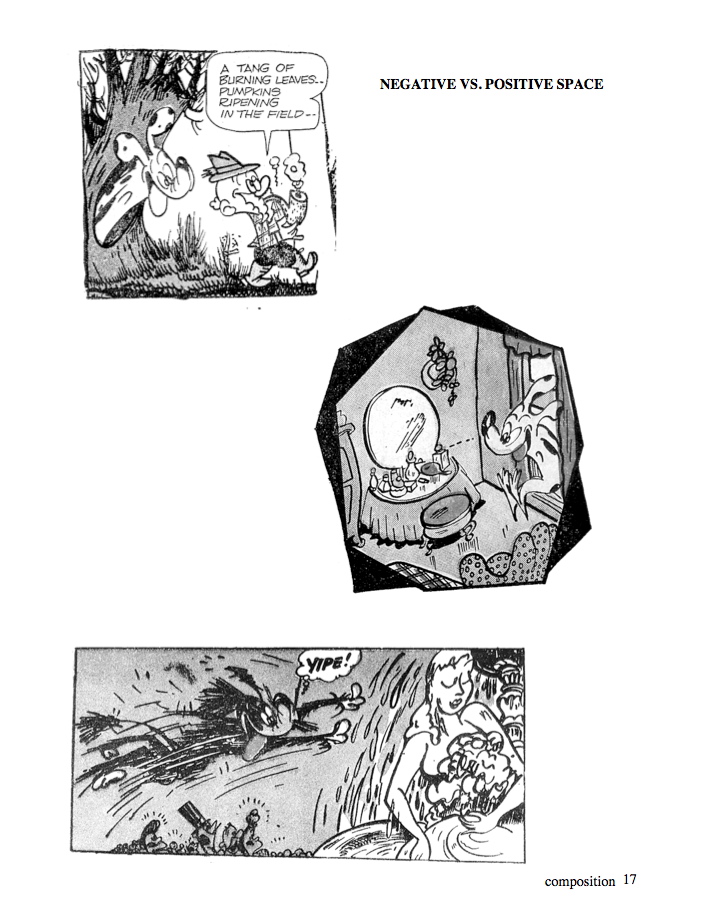

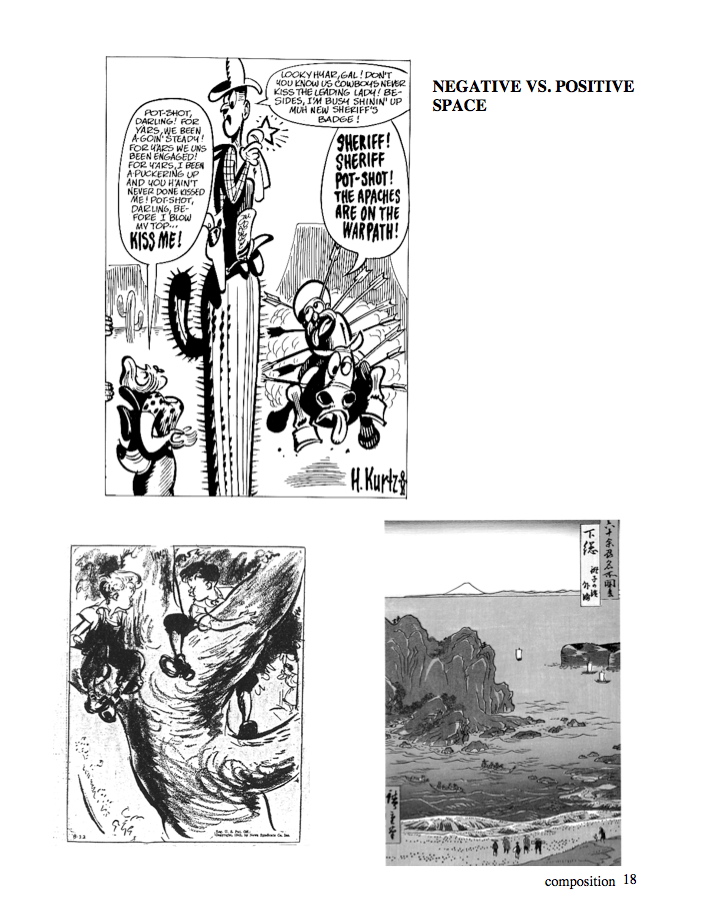

Negative / Positive Space

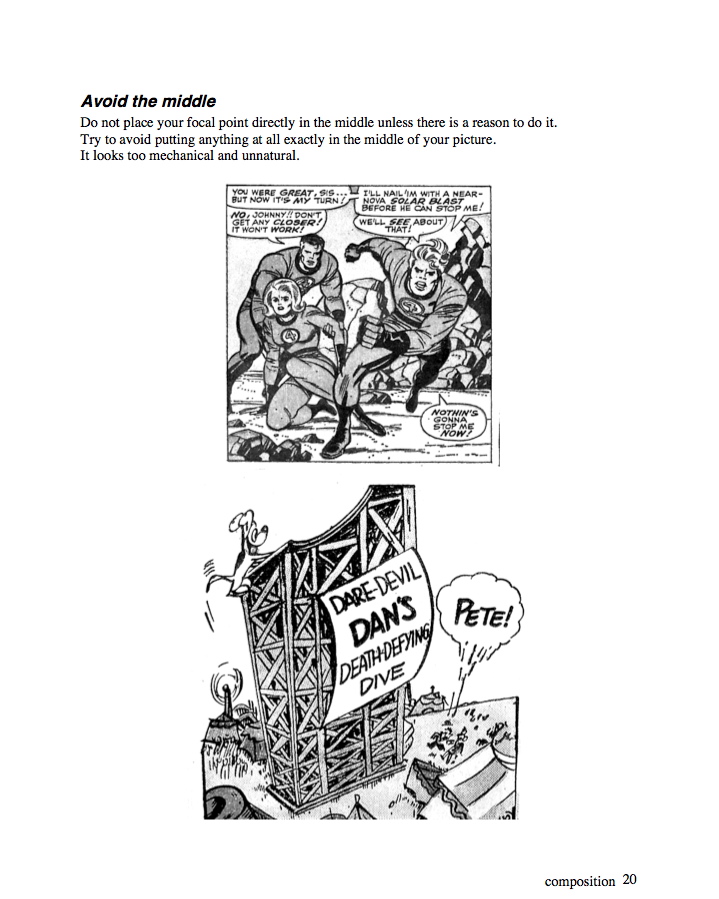

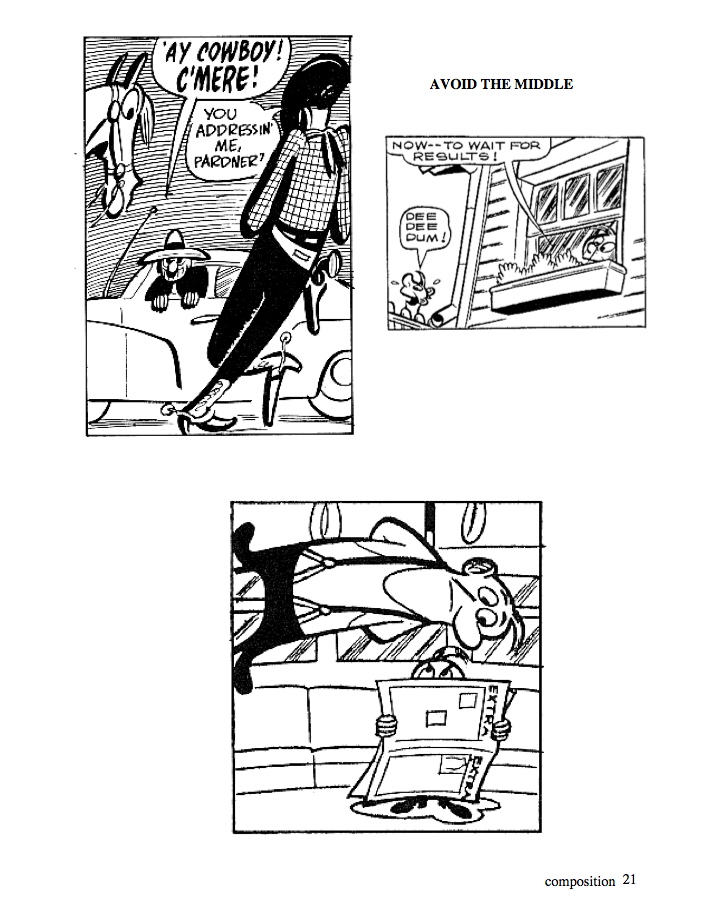

Avoid the Center

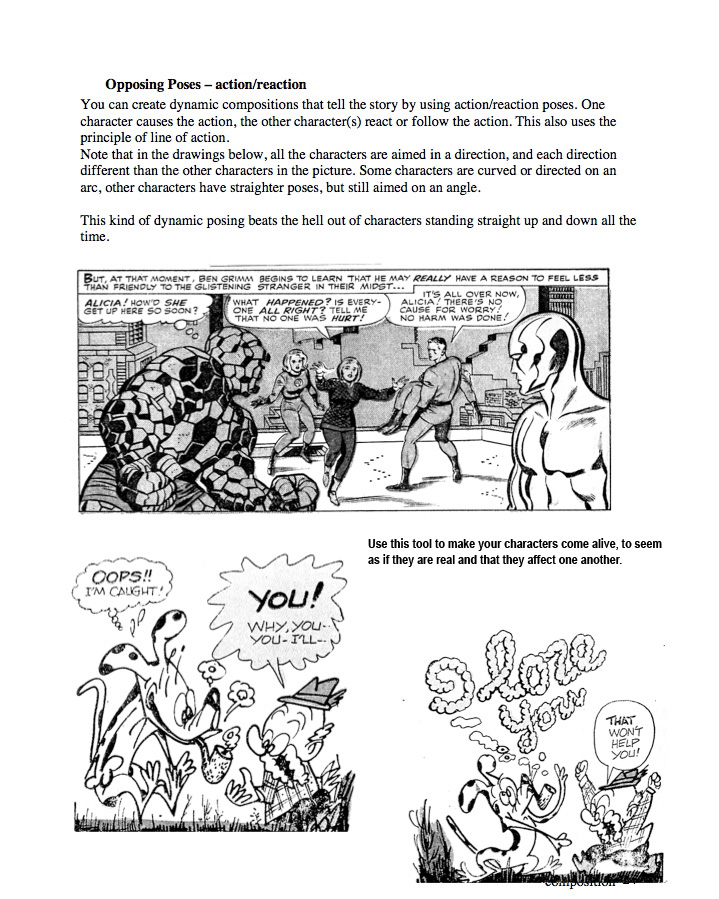

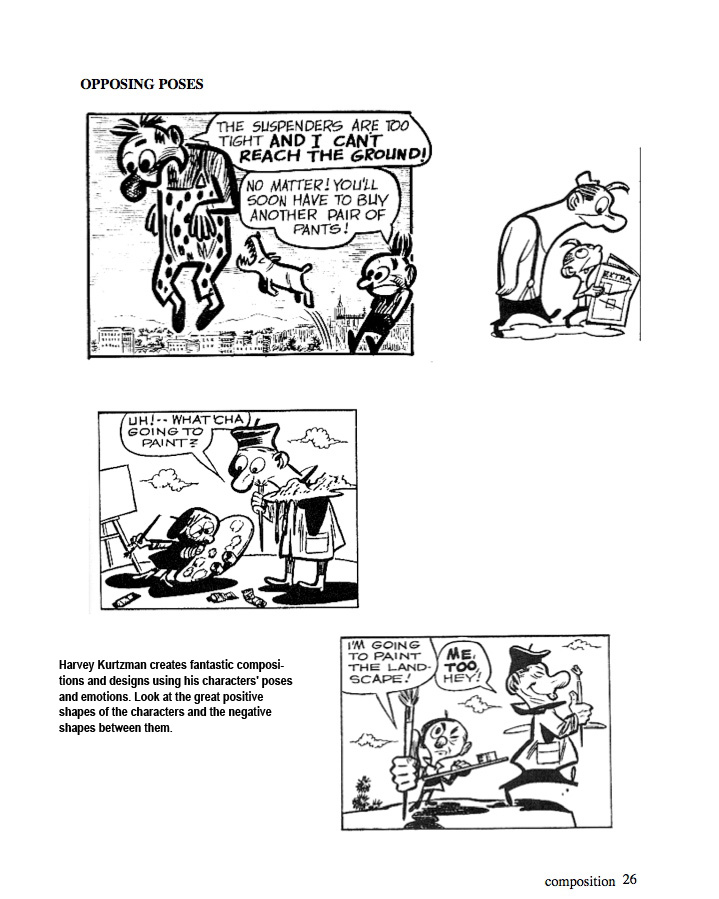

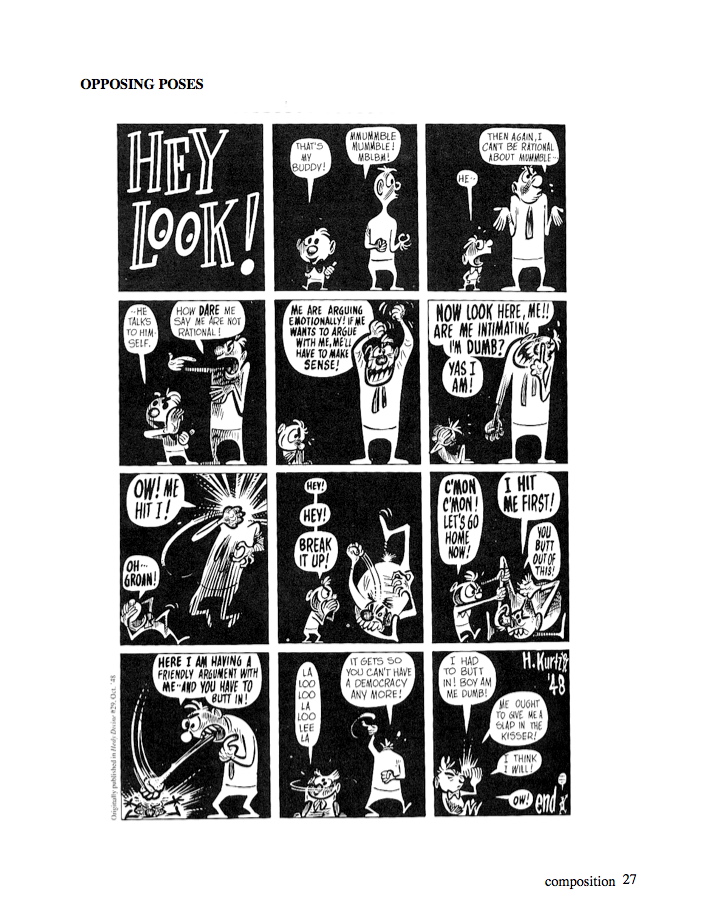

Opposing Forces

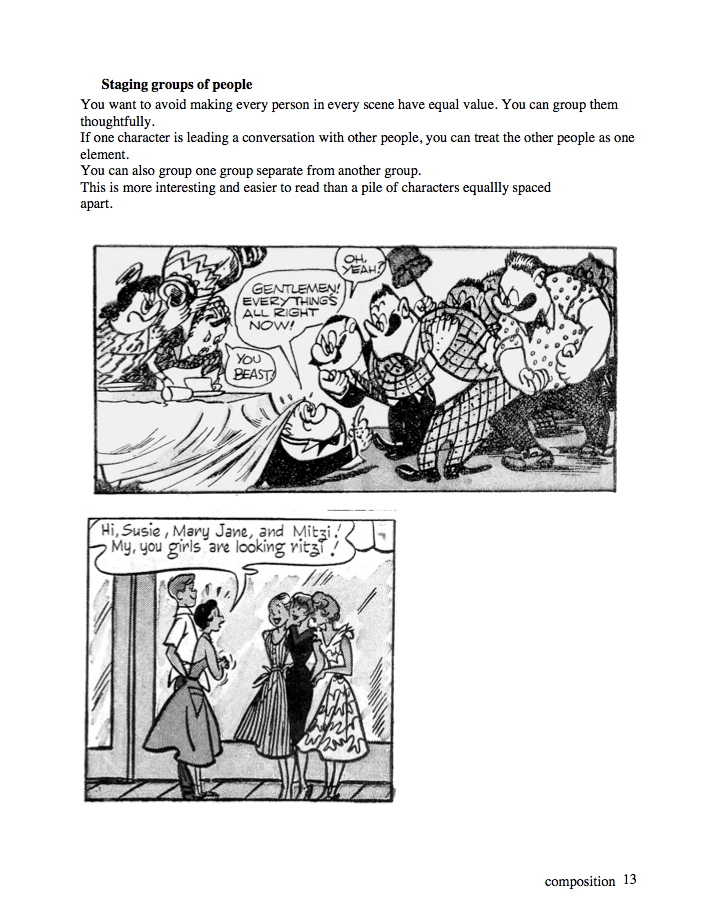

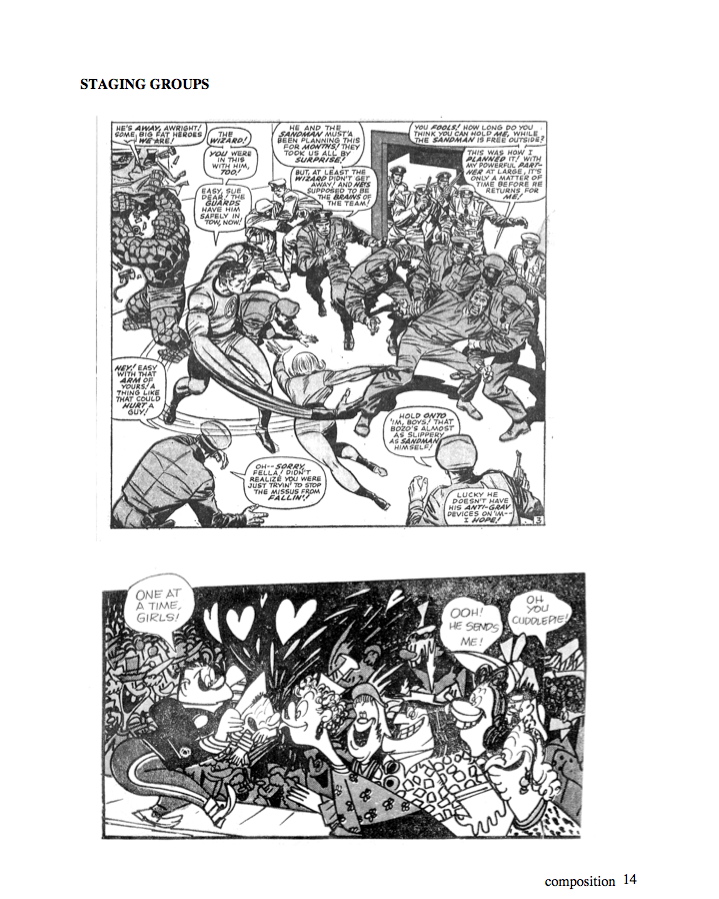

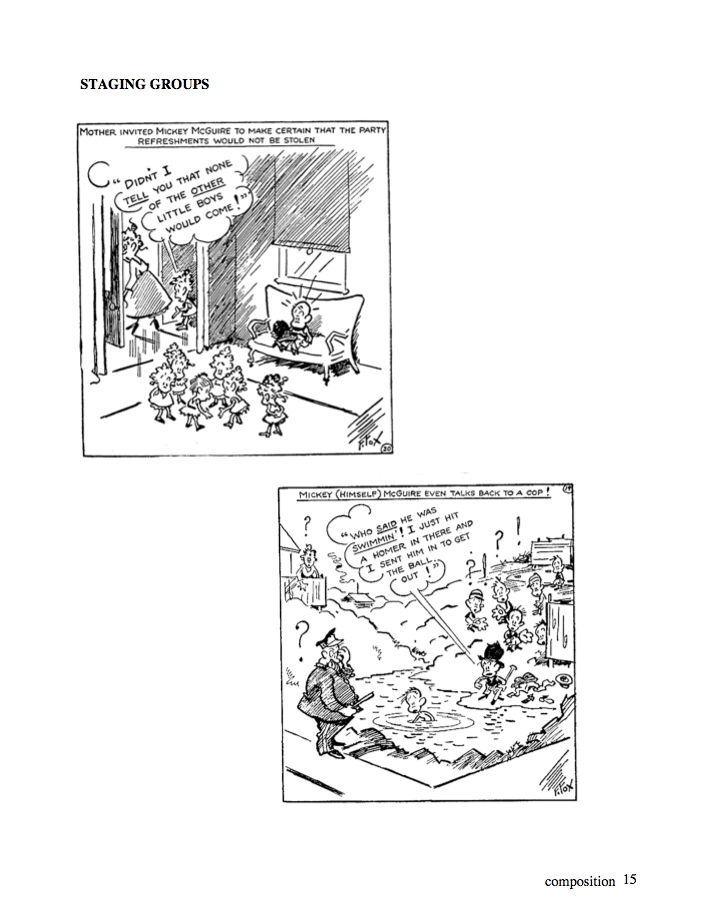

Staging in Groups

Hierarchy / Visual Balance

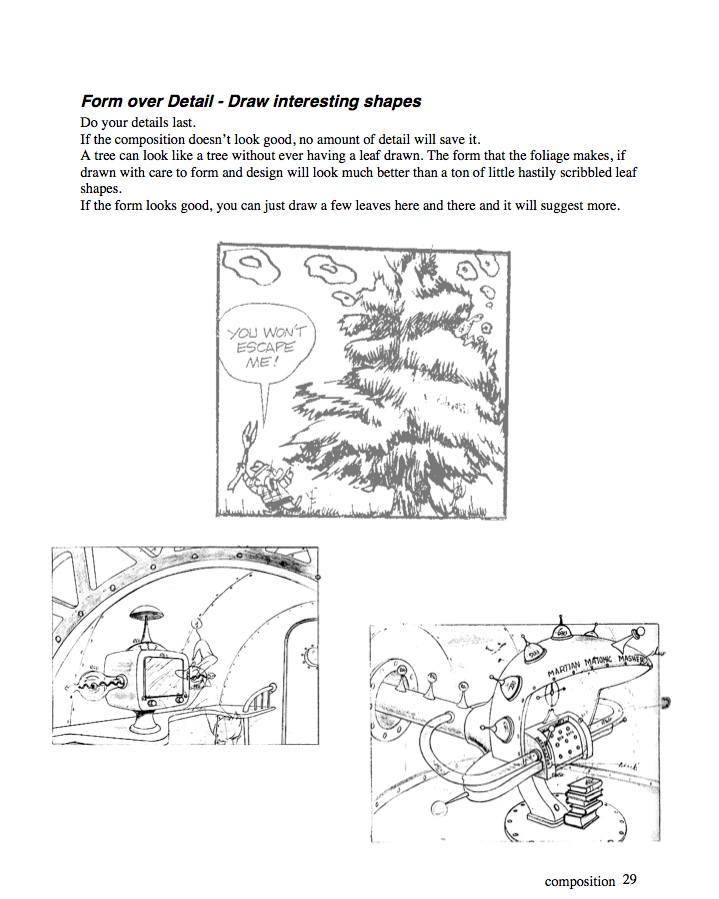

Form Over Detail

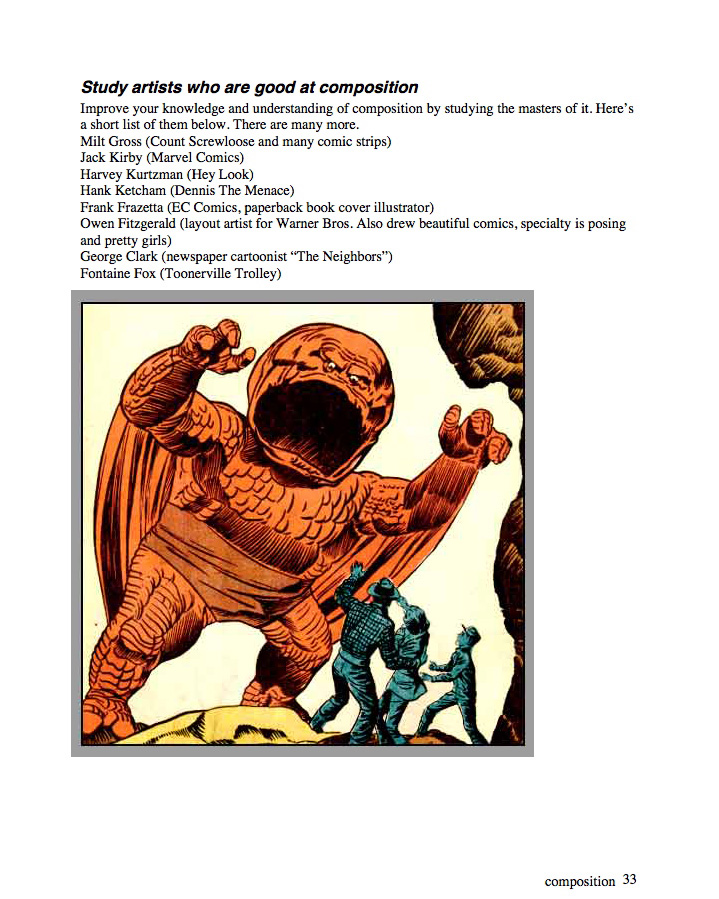

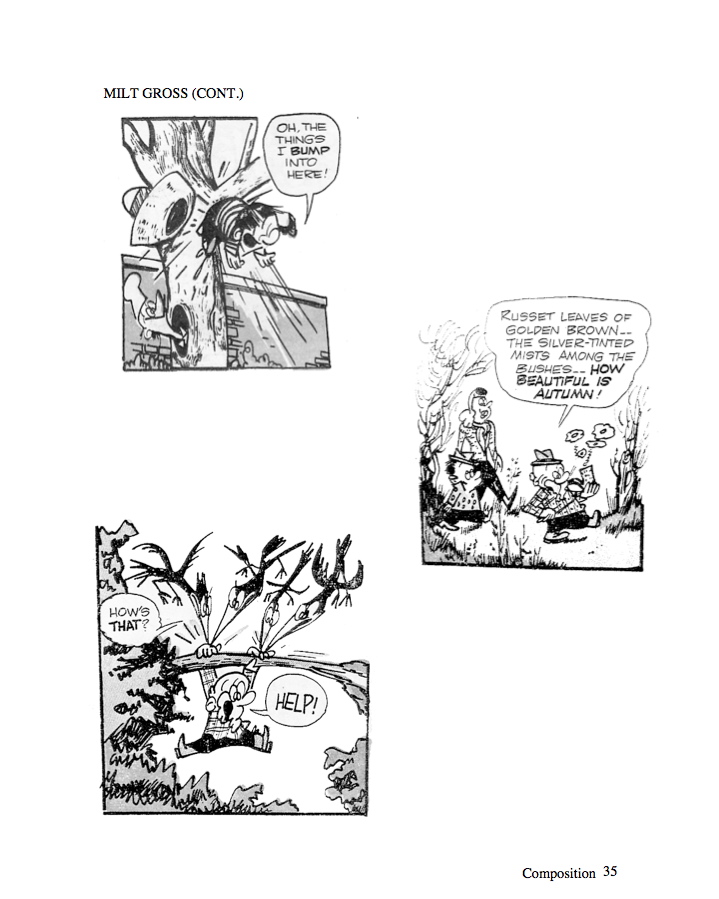

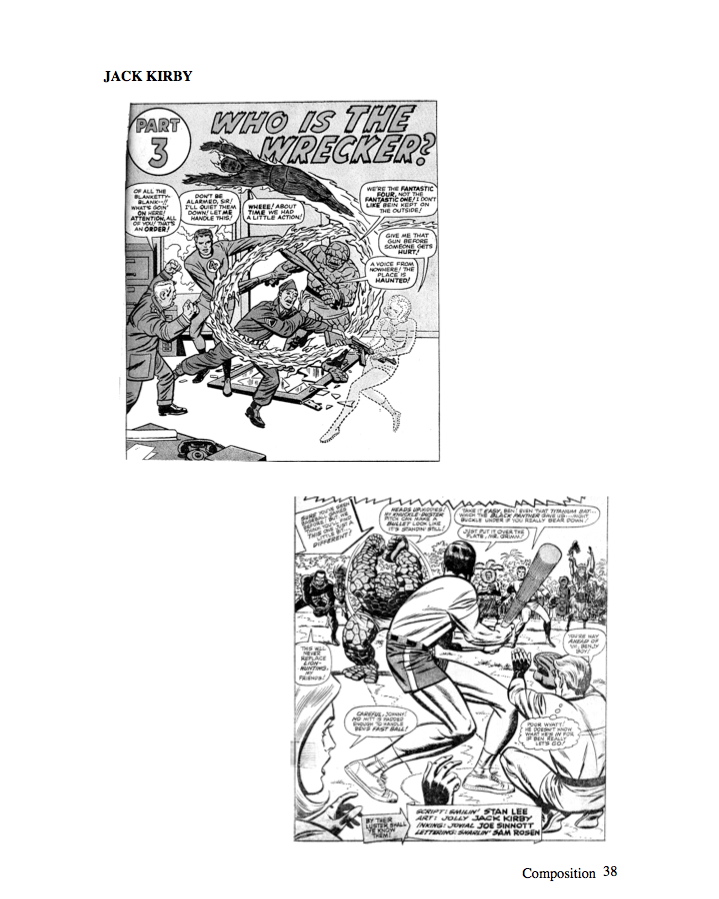

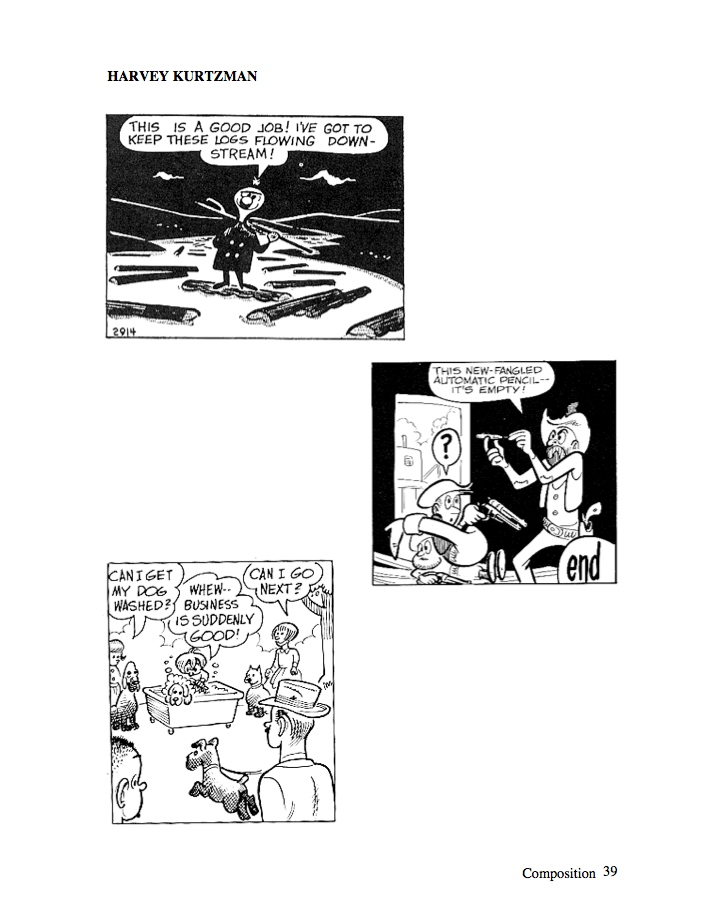

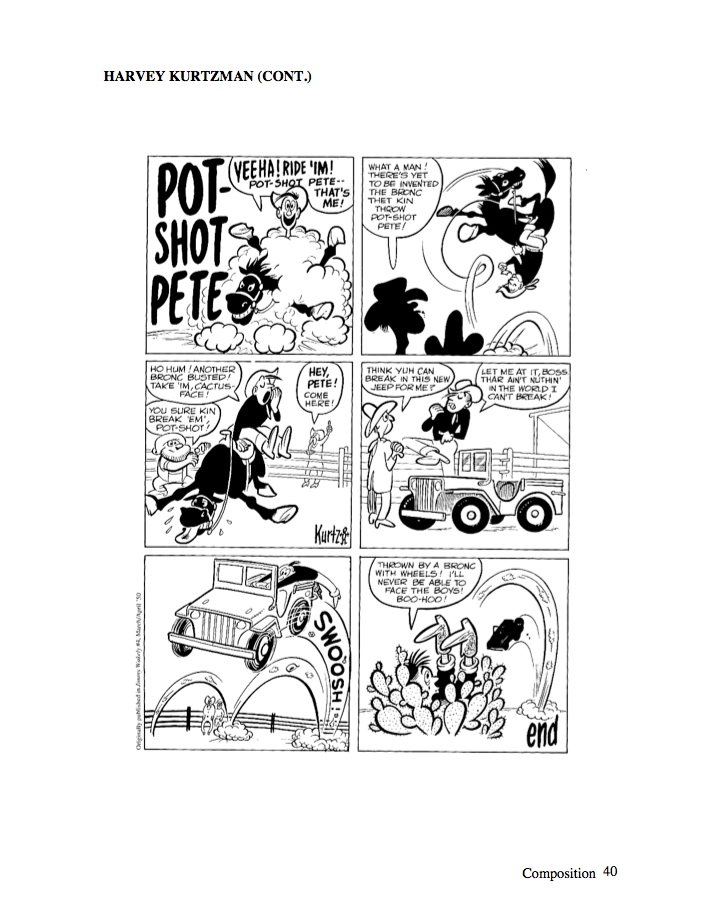

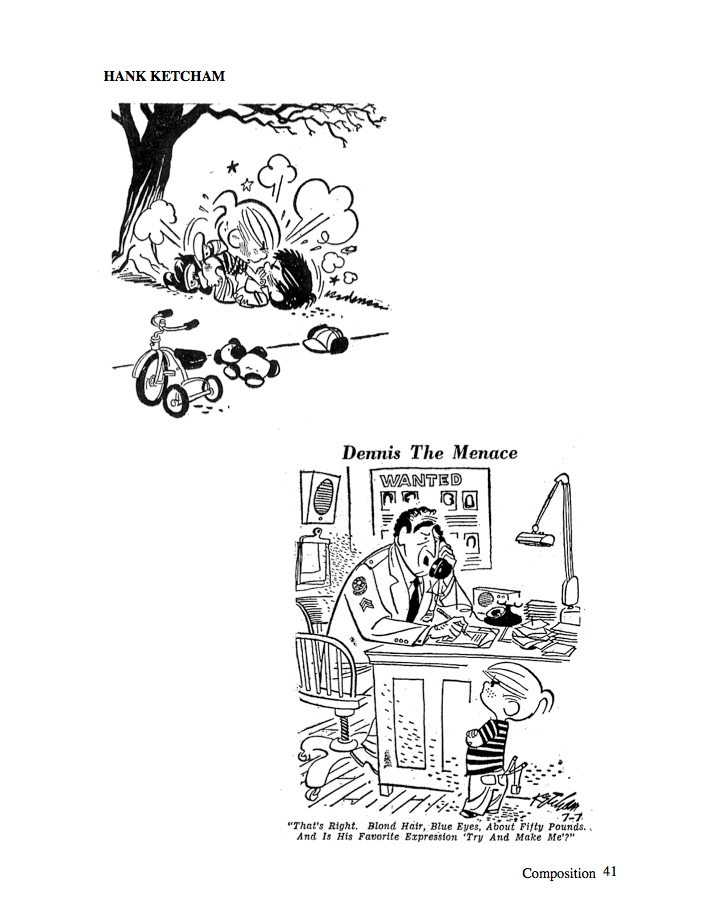

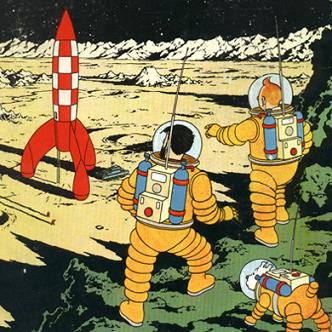

There is much you can learn from studying the many styles of composition practiced by master comicbook/comic strip artists and illustrators...

The Main Principles:

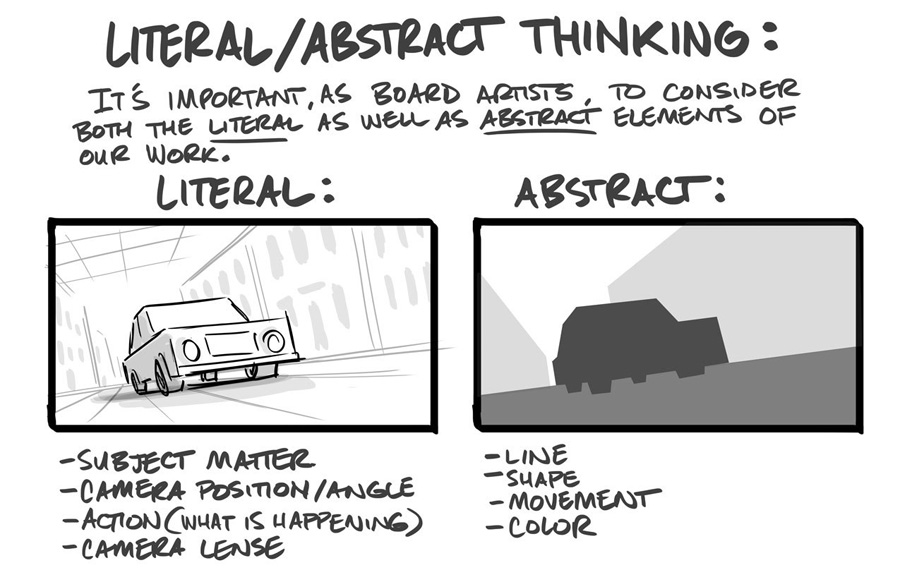

The purpose of all composition in comics, storyboarding, graphic design, illustration, or filmmaking is to achieve clarity in the visual layout and presentation of the static or moving image.

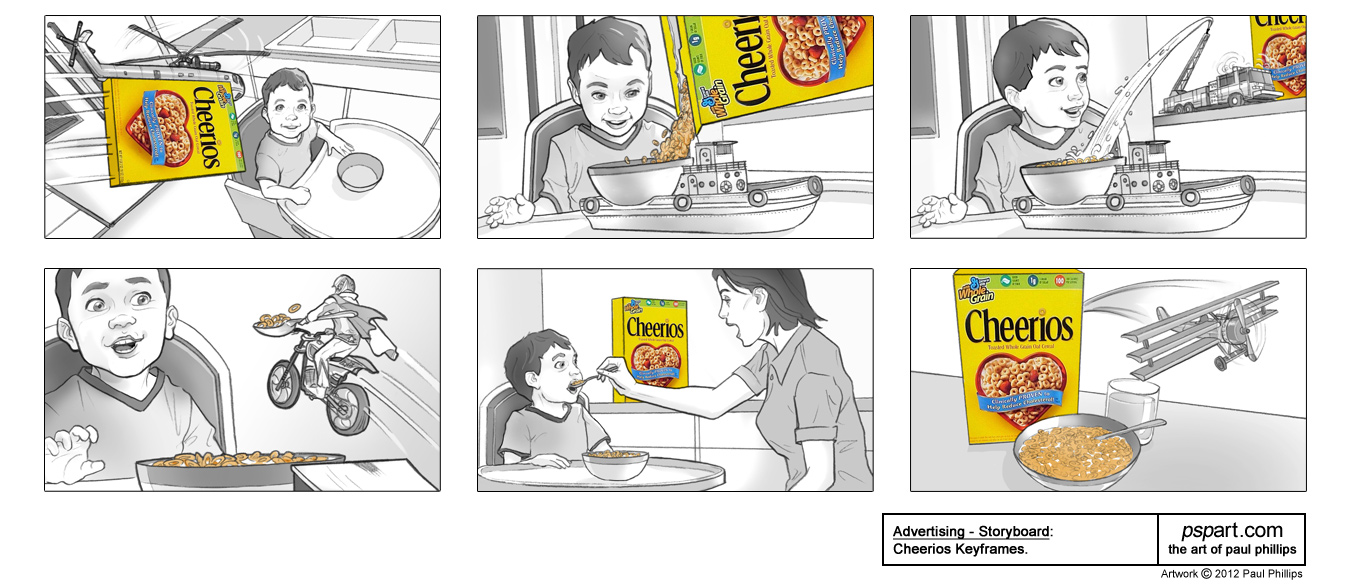

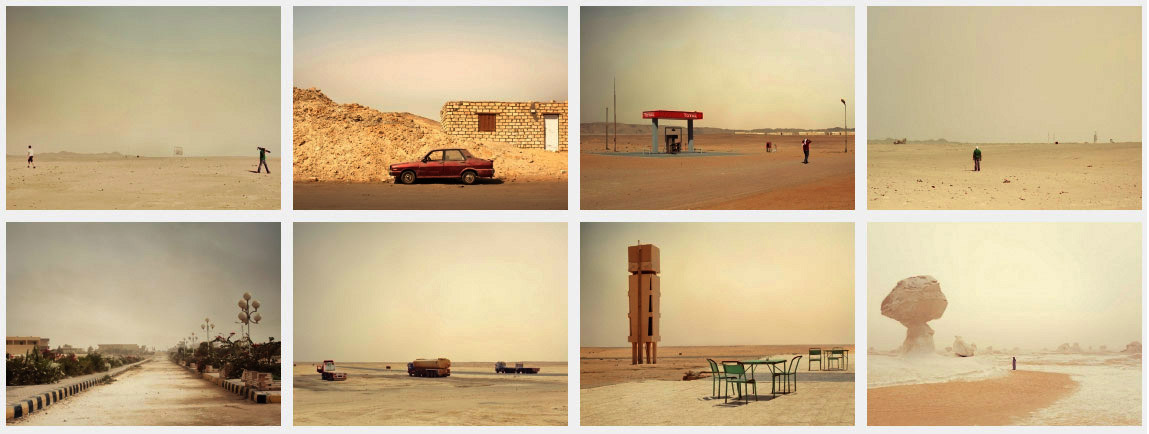

look at TV commercials for inspiration as how to tell a thirty-second story clearly and effeciently. Great commercials are made with a ton of economy, discipline and smart choices. Also, many times they start in a very familiar situation so that the audience gets oriented quickly and knows exactly where we are....then you can take a leap into "the fantastic", if that's what you want to do, or turn the everyday on it's head for comedic effect.

These four Chef-Boy-Ar-Dee commercials are good examples for Clarity.

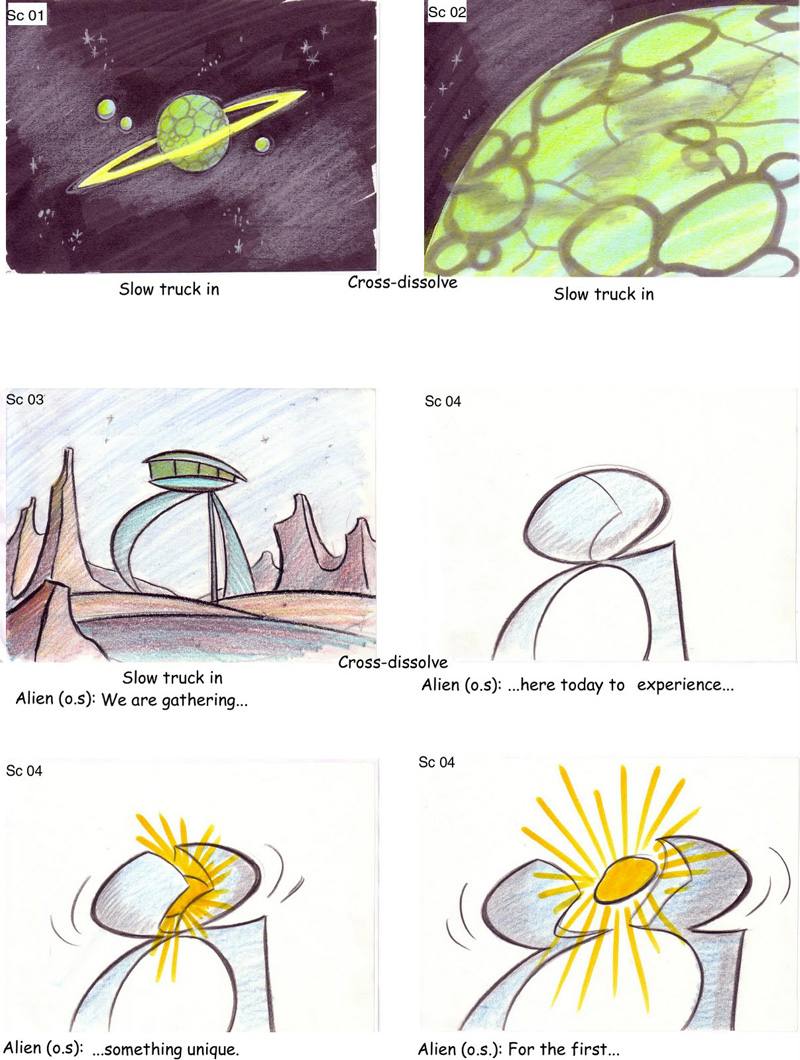

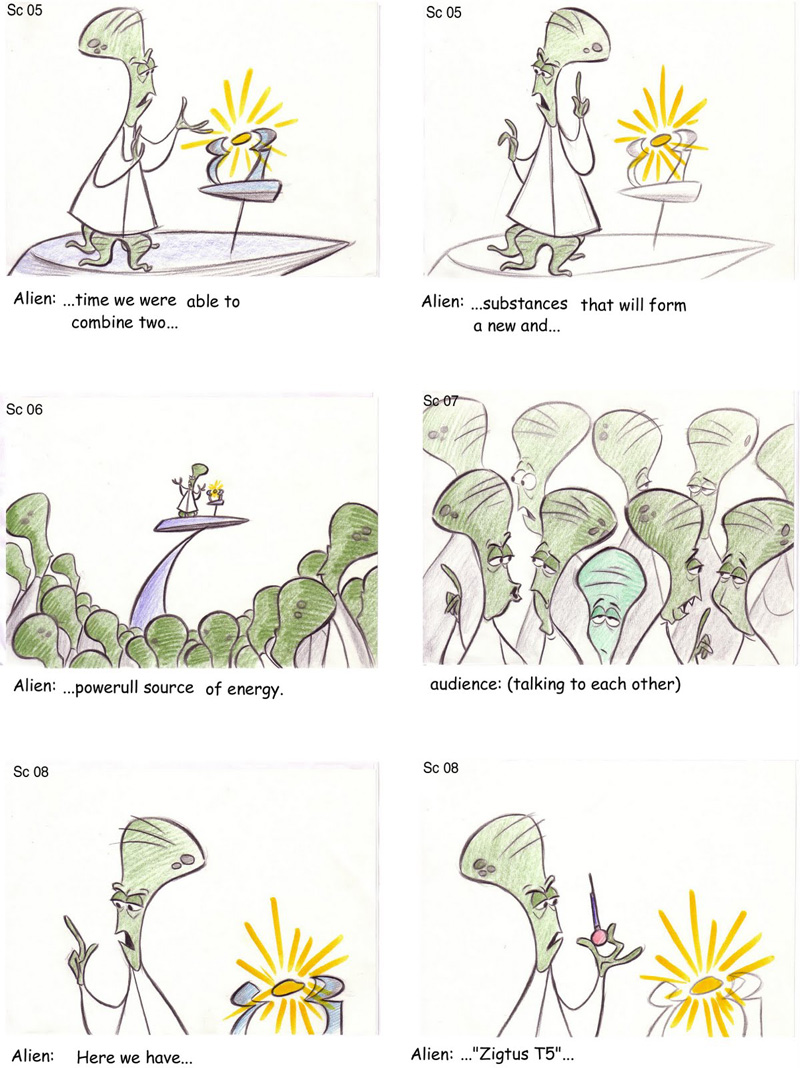

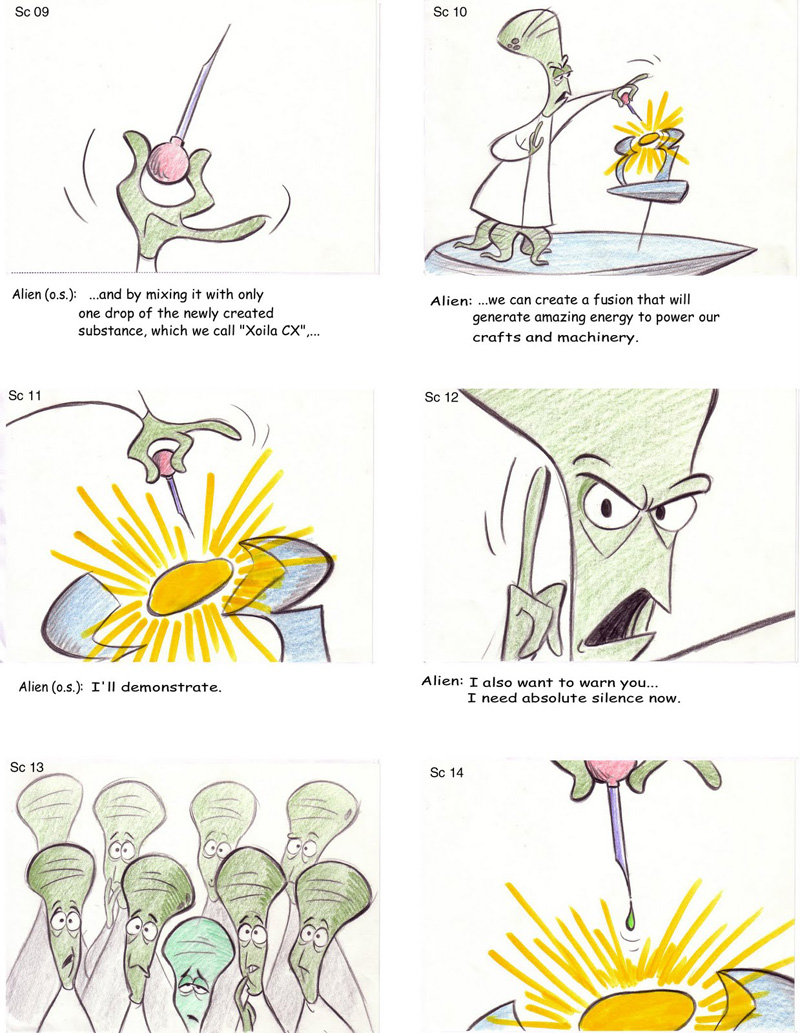

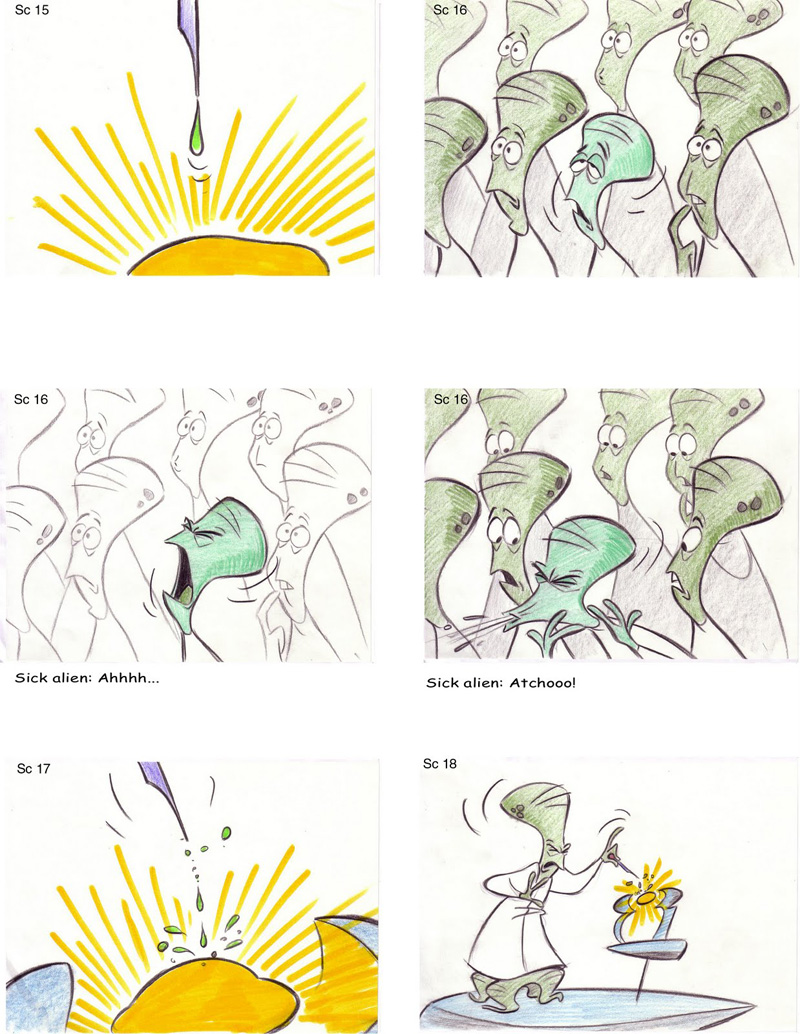

Let's analyze the importance STORYBOARDING a short film or commercial.

I boiled story down to three "C's". The first "C" is "CLARITY".

This one is particularly important for a storyboard artist in the process of visualizing a script or idea because you are working within a very small box, in both the length of your film and your "production schedule". When making a short film clarity is of the utmost importance because you don't have time to explain a lot. If you're trying to make a film about an exotic planet where all the rules are different from Earth, by the time you've acclimated the viewer to your world and explained all the rules, your film is over.

So I always suggest that short film directors look at TV commercials for inspiration as how to tell a thirty-second story clearly and effeciently. Great commercials are made with a ton of economy, discipline and smart choices. Also, many times they start in a very familiar situation so that the audience gets oriented quickly and knows exactly where we are....then you can take a leap into "the fantastic", if that's what you want to do, or turn the everyday on it's head for comedic effect.

Clarity is tougher than most people realize I think, even professional storyboard artists and film directors have a hard time with this. It's easy, once you've thought through your idea, to think that your drawings are explaining what's inside your head, but the viewer doesn't have the benefit of hearing your thoughts. The drawings (and eventually, the animation) have to carry it all. That's a very tough limitation, and you need to keep your "objective eye" in check, so that you can step back and look at your work once in a while and see it the way fresh eyes will see it. Or find someone you trust and bounce it off them once in a while.

Okay, the next two "C's" are CHARACTER and CONFLICT. You've probably heard all this before, but it's all vitally important, and it's basically what the directors, writers and story artists spend all their time talking about in the story room while they craft movies at Disney, DreamWorks and Pixar.

Basically, the "CHARACTERS" part means that you should always strive to create characters that are original, entertaining, appealing, and that the audience can empathize with...meaning that they like the characters and are willing to root for them to get what they want. Then the audience will care when your characters end up in....

...CONFLICT, which of course is the heart of all storytelling. Without conflict you don't really have a story. In general, the bigger the conflict, the more that is at stake in your movie, the bigger the odds against your characters, the more interesting the story.

So if you have characters that the audience is actually rooting for, and conflict that seems almost insurmountable that they have to resolve to get what they want, then you have a great story.

Also, one last thing: a great story is one that ends by resolving the conflict in an unexpected way that the audience doesn't see coming. But I don't know how to make that idea start with a "C" so piss off.

The main point here, start small, someday... write then storyboard a short 30 sec film, storyboard several times, several different ways. Cut these images together in sequence. You'll see what huge challenge it can be to clearly and accurately tell the story in an effecient and entertaining way.

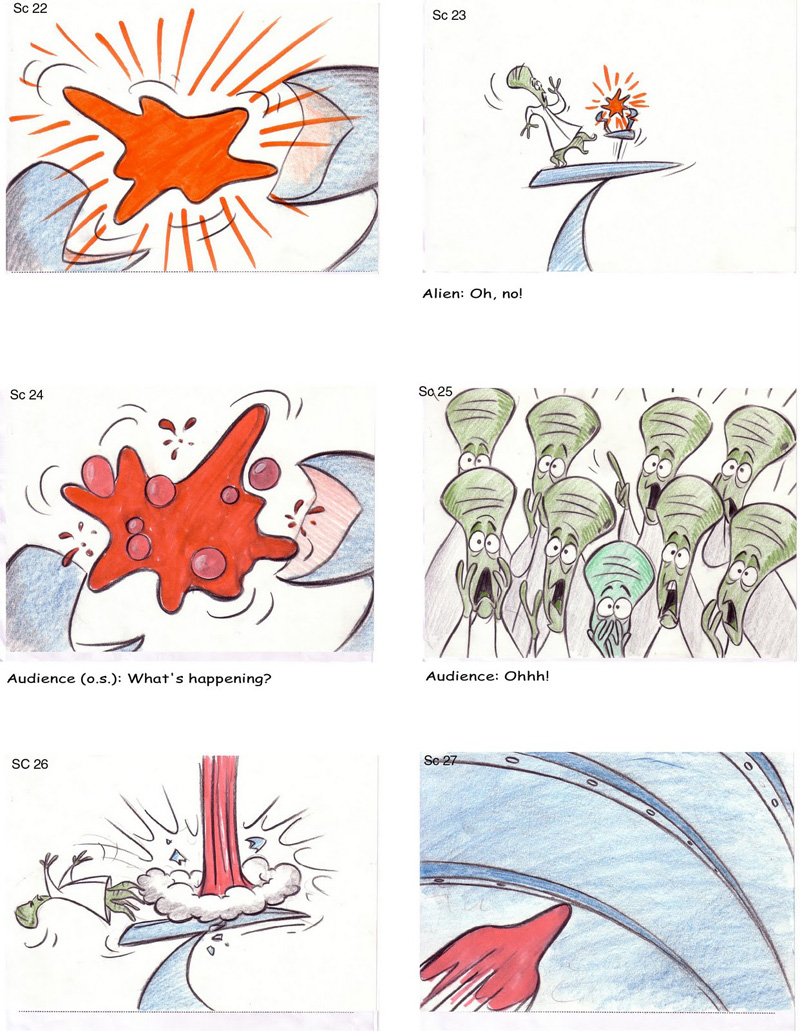

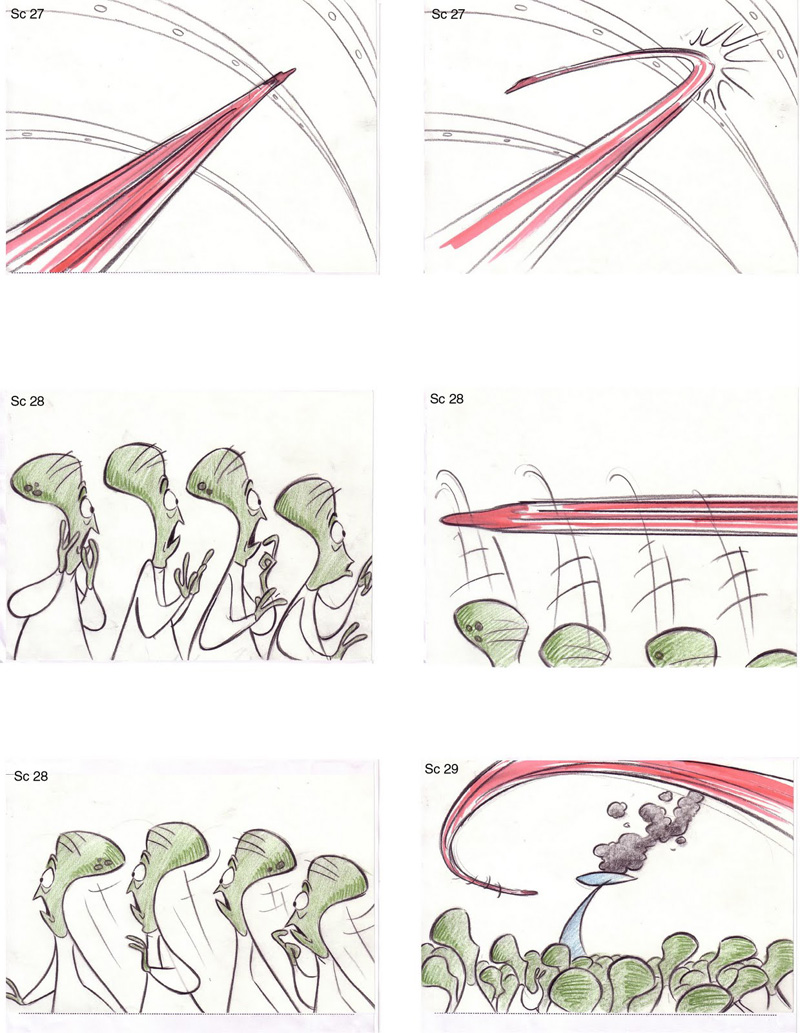

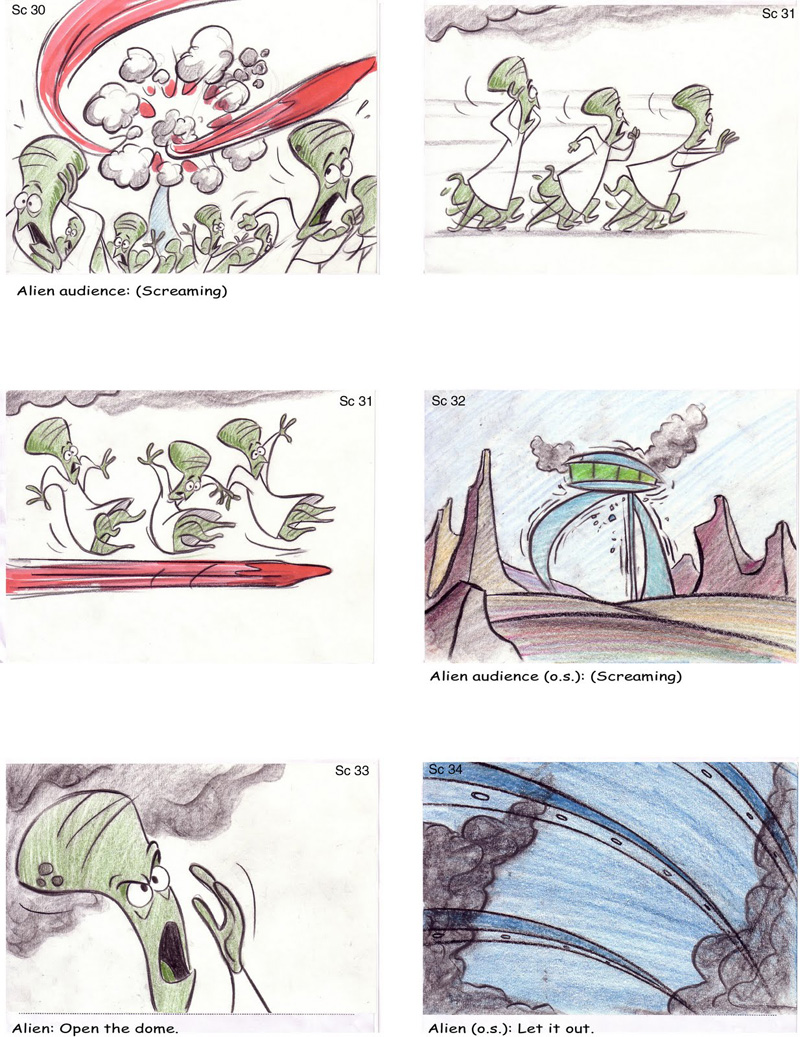

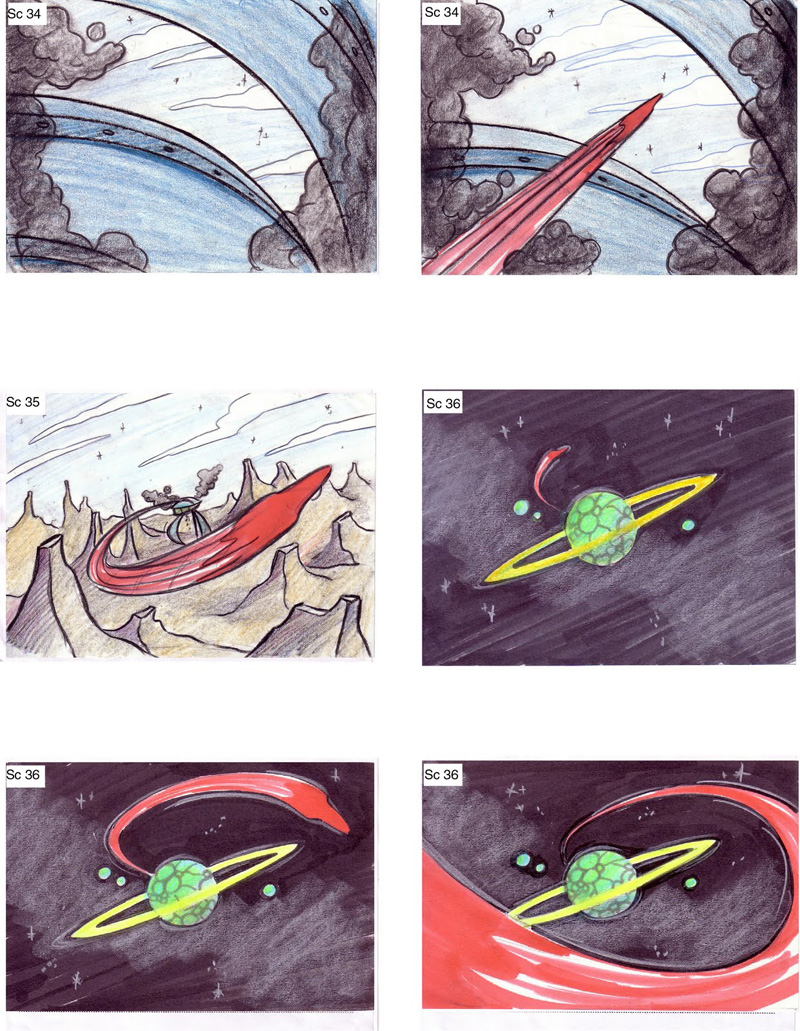

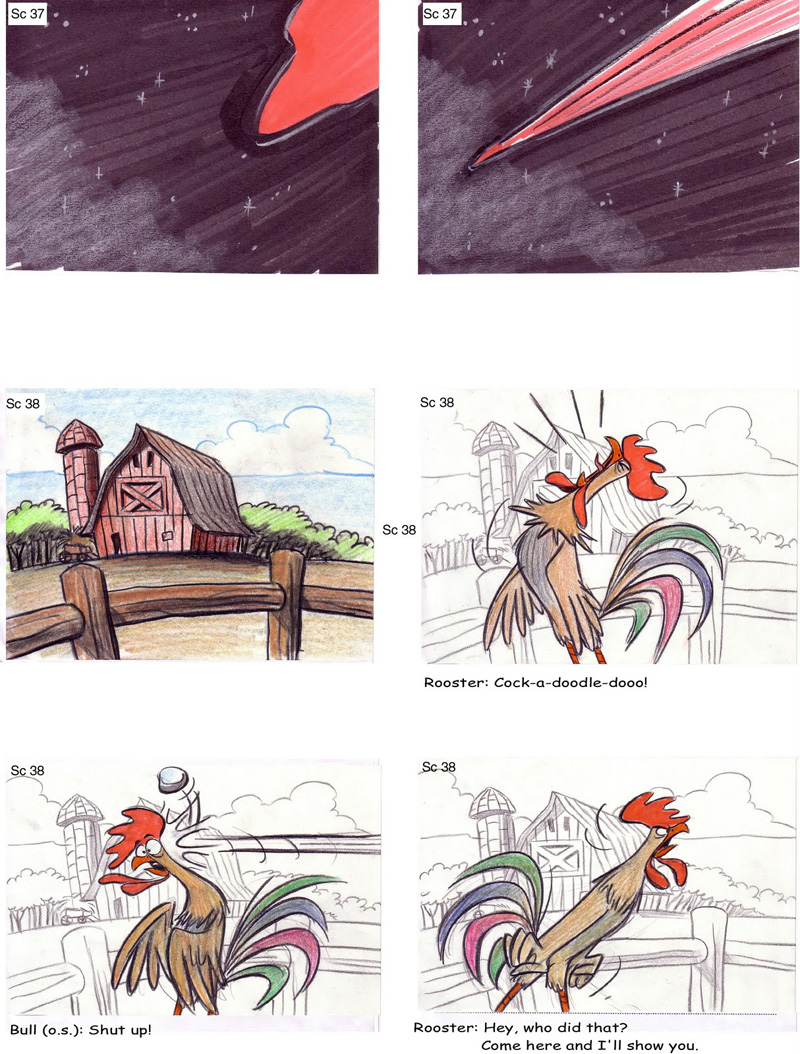

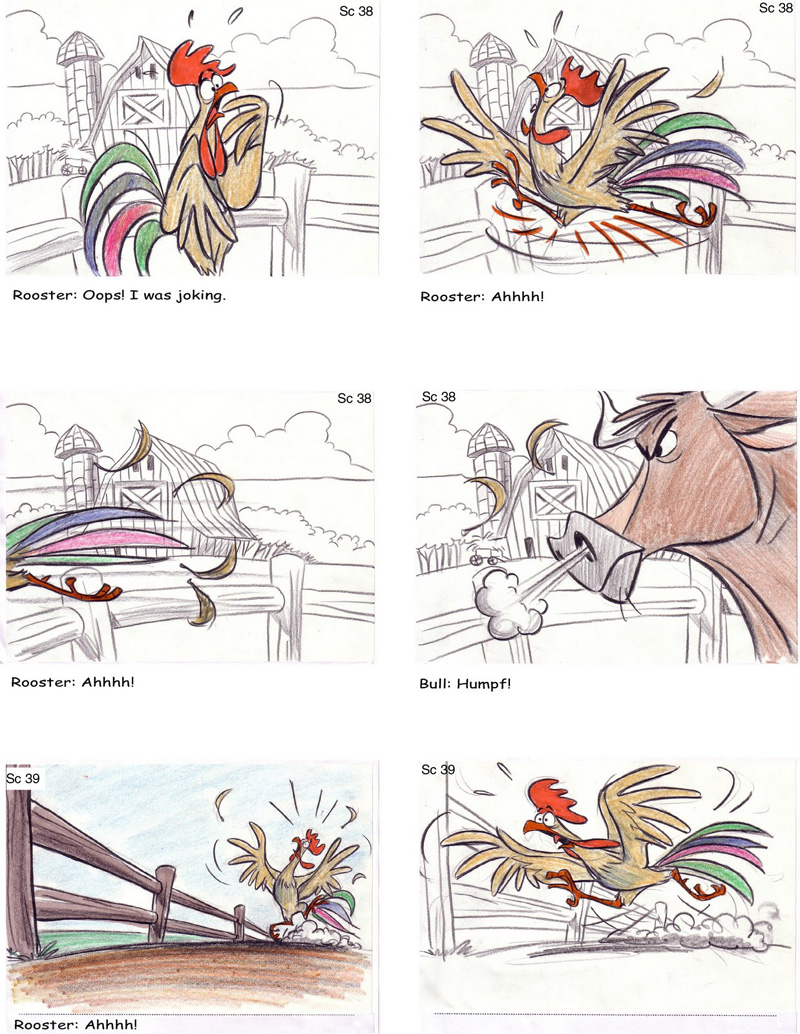

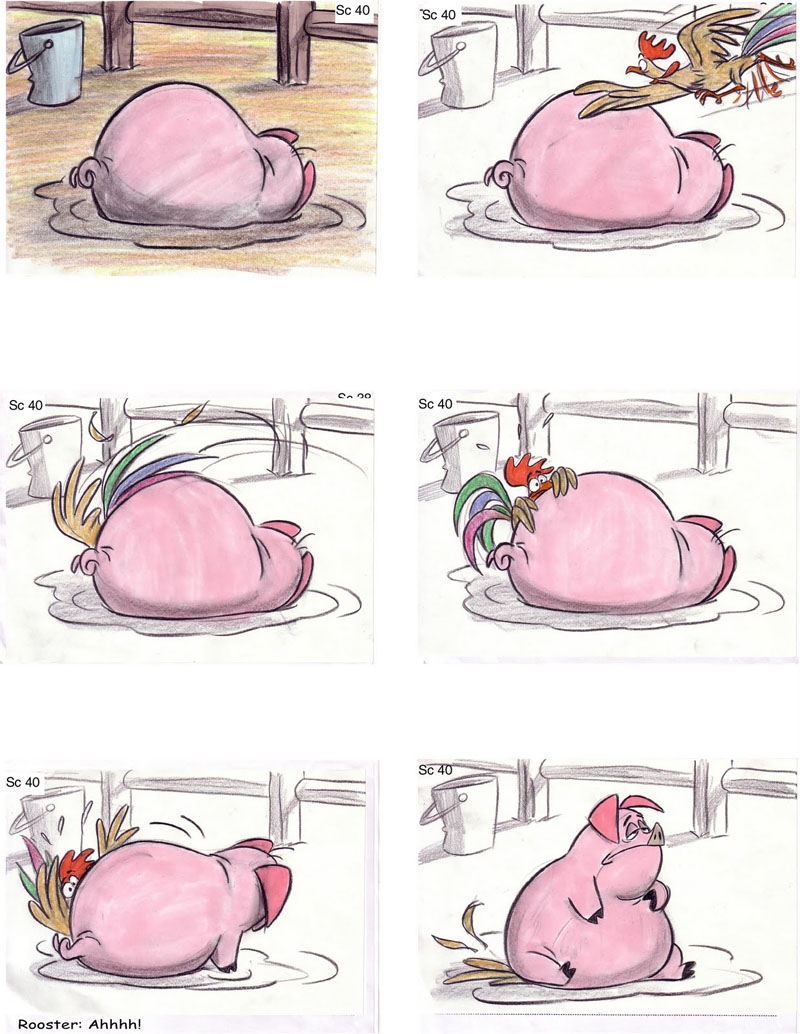

Here is a pitch Exit 73 Studios created for Nickelodeon that was ultimately turned down, but it gives you a glimpse into their pre-production process. The entire storyboard/animatic phase is done completely in Flash, so we are left with very little guess work in the layout stage. The scratch audio and music in house.

If your interested you can download the pitch book here... exit73studios.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Market-WarriorsSmall.pdf

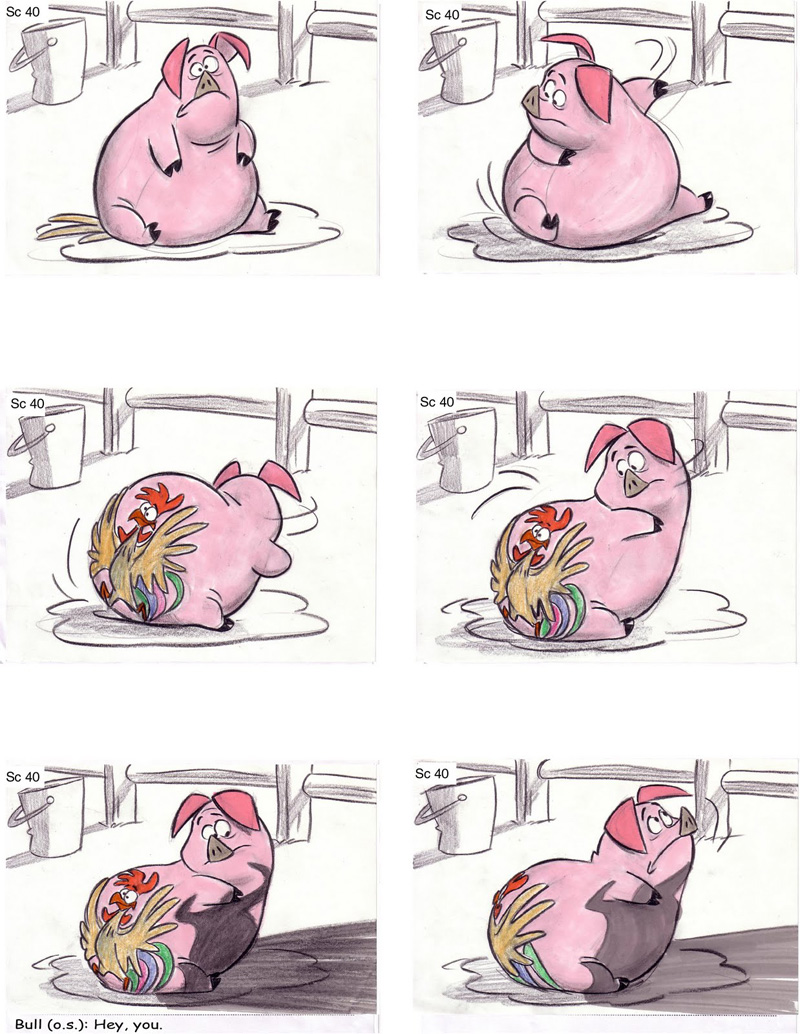

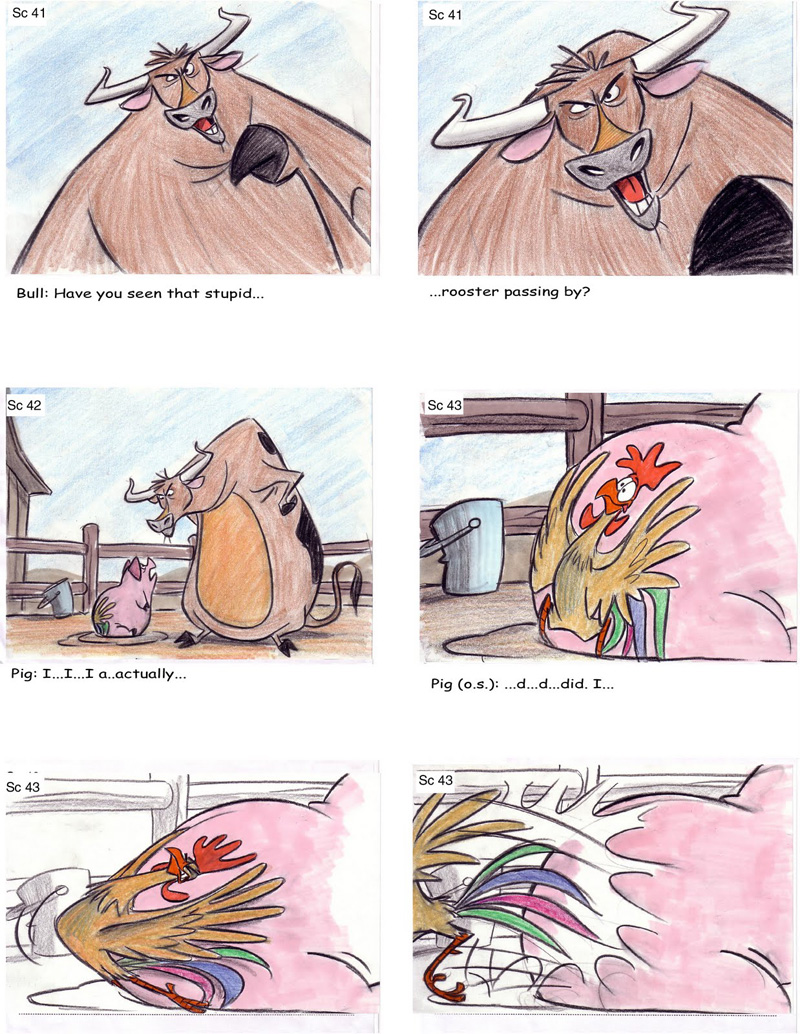

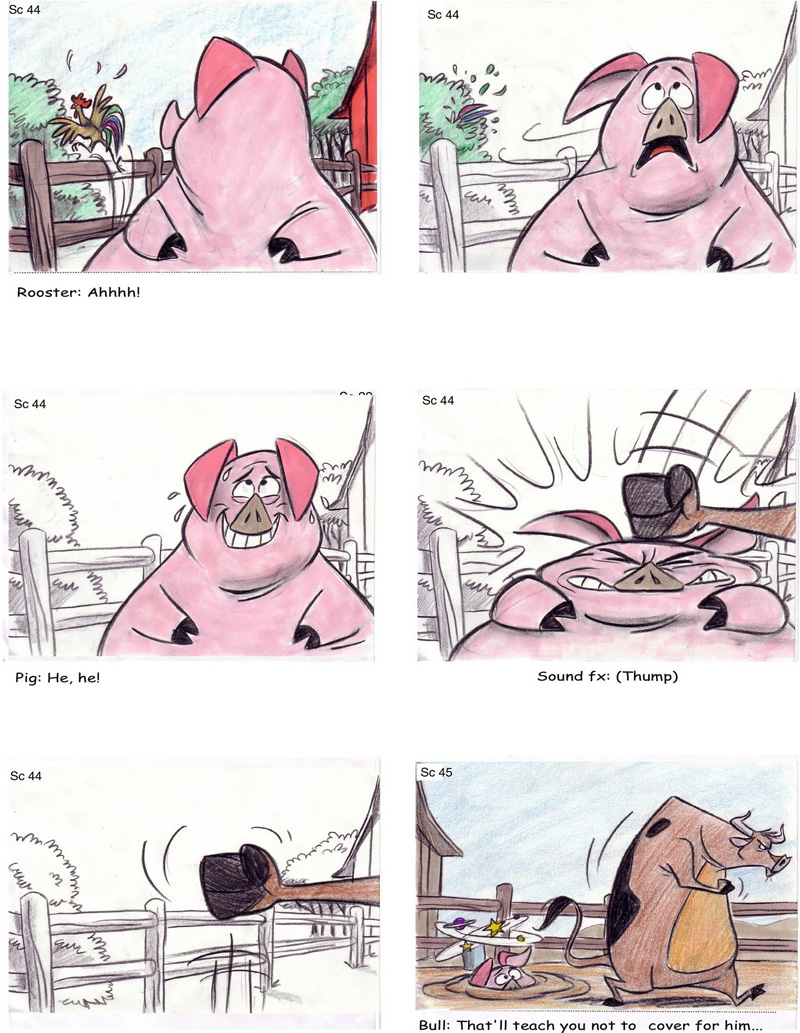

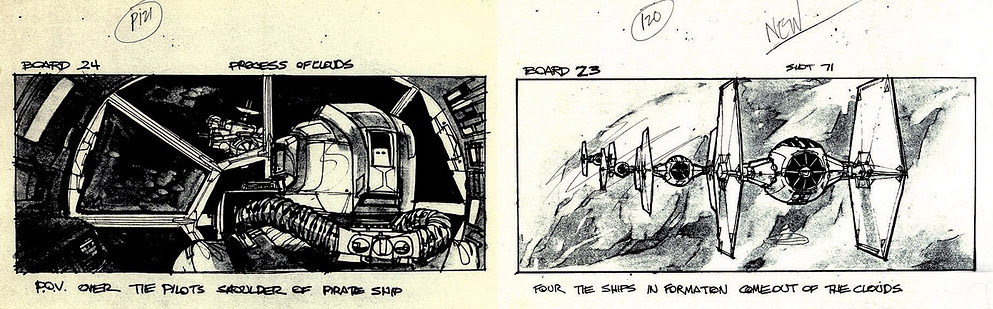

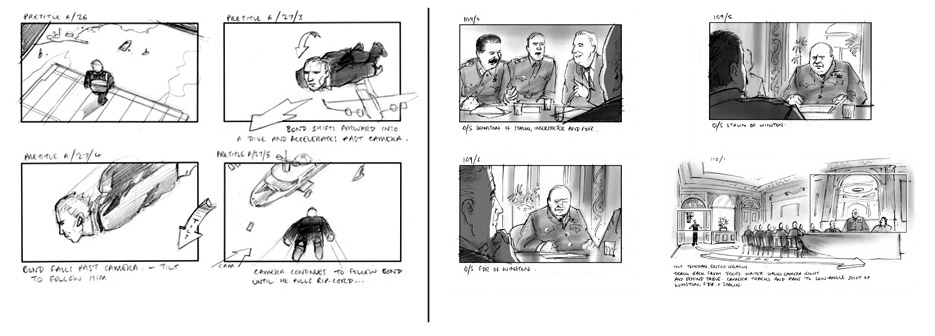

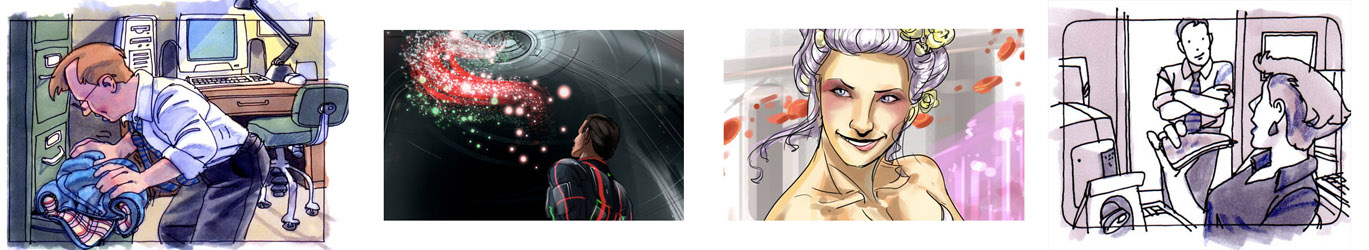

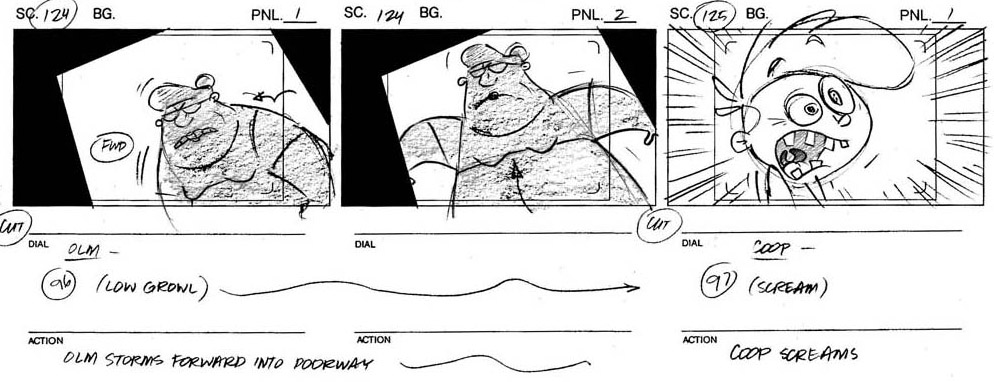

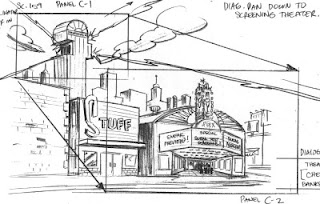

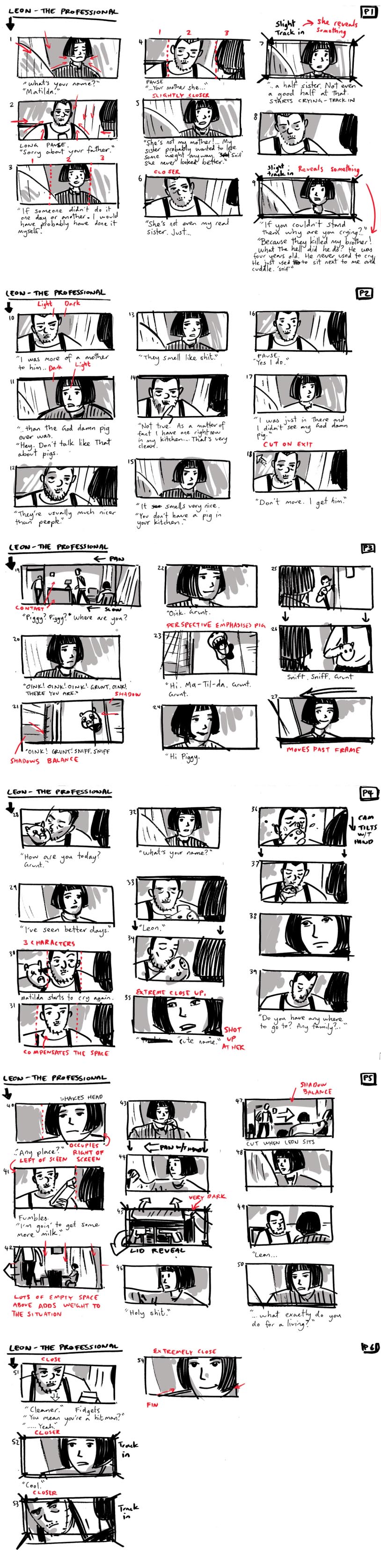

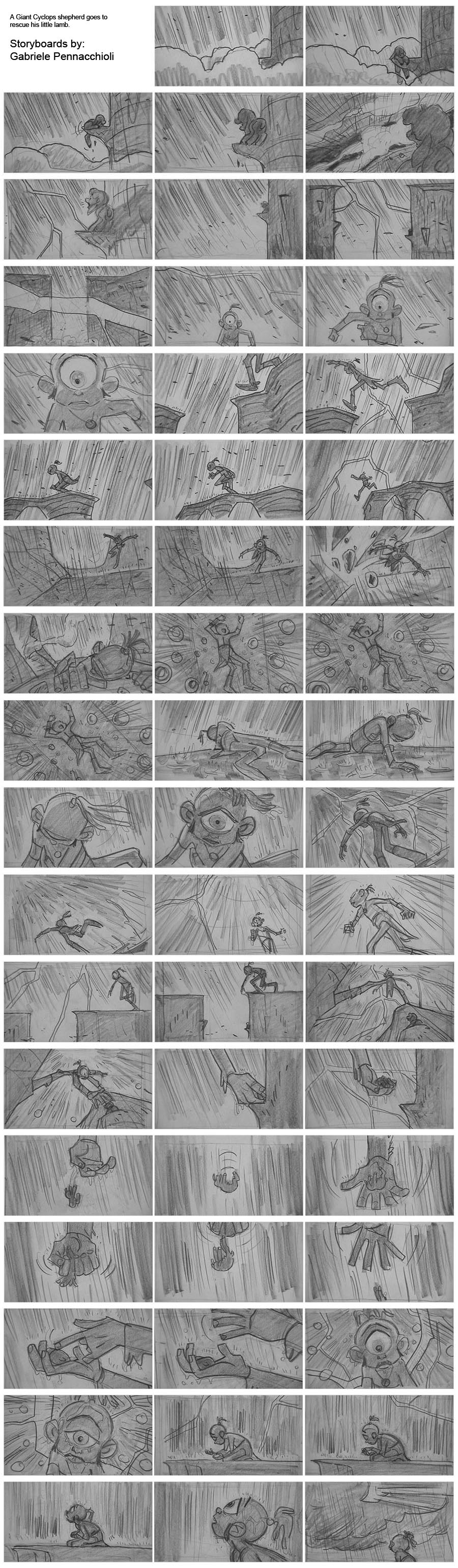

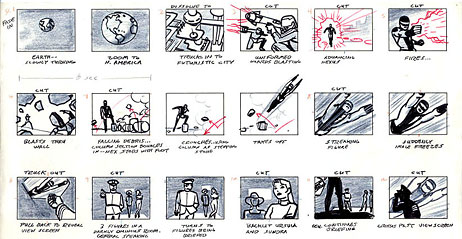

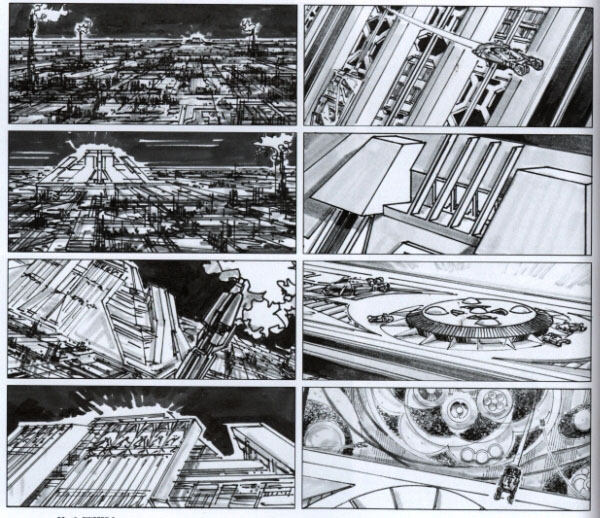

Observe the simple use of various angles and framing techniques in this storyboard:

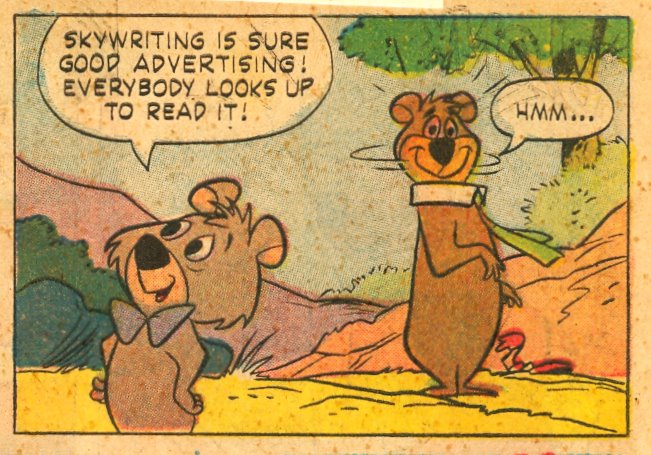

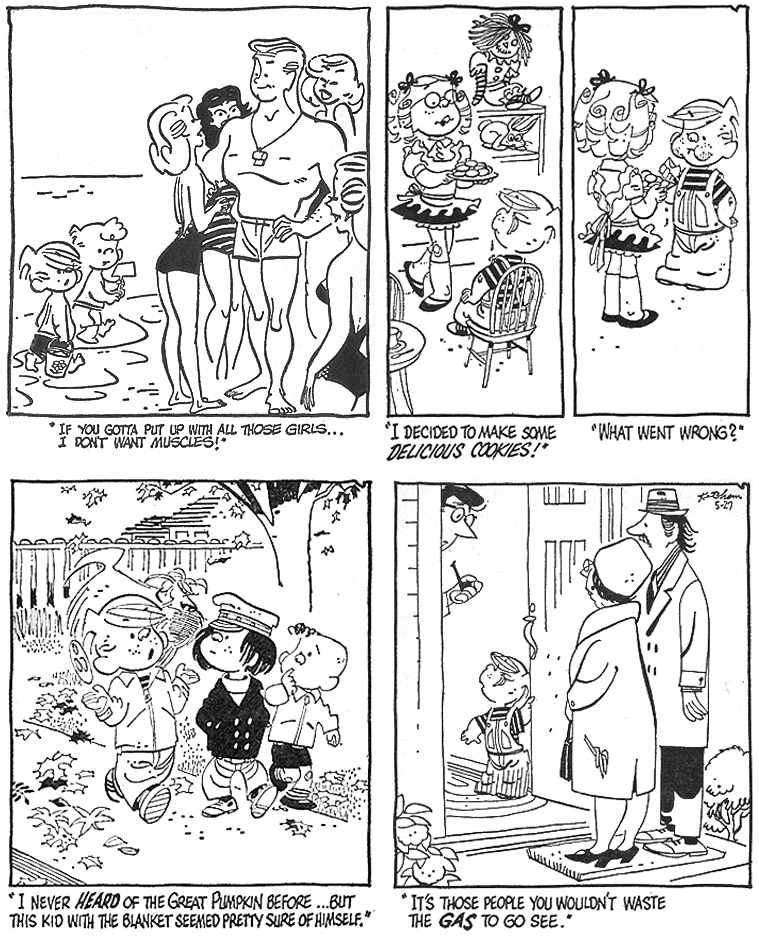

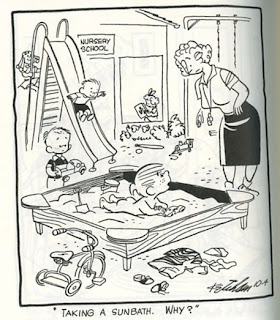

Animator Hank Ketcham created Dennis the Menace, he began the comic strip in the 50s and there was always great staging and thoughtful designs.

Traditional animators often talk about "economy of line"; describing as much as possible with the fewest lines, since every line has to be drawn over and over again. The same can be said for storyboard artists, it takes years of practice to become very effecient with your pencil or stylus pen, to visually display a layout of a shot, the weight of a pose, the emotion in a posture, the basic shapes and forms that make up the clear and effective composition of a scene with as few lines as possible.

Applying Contrast and Tone Specifically to Storyboarding

Keep It Simple

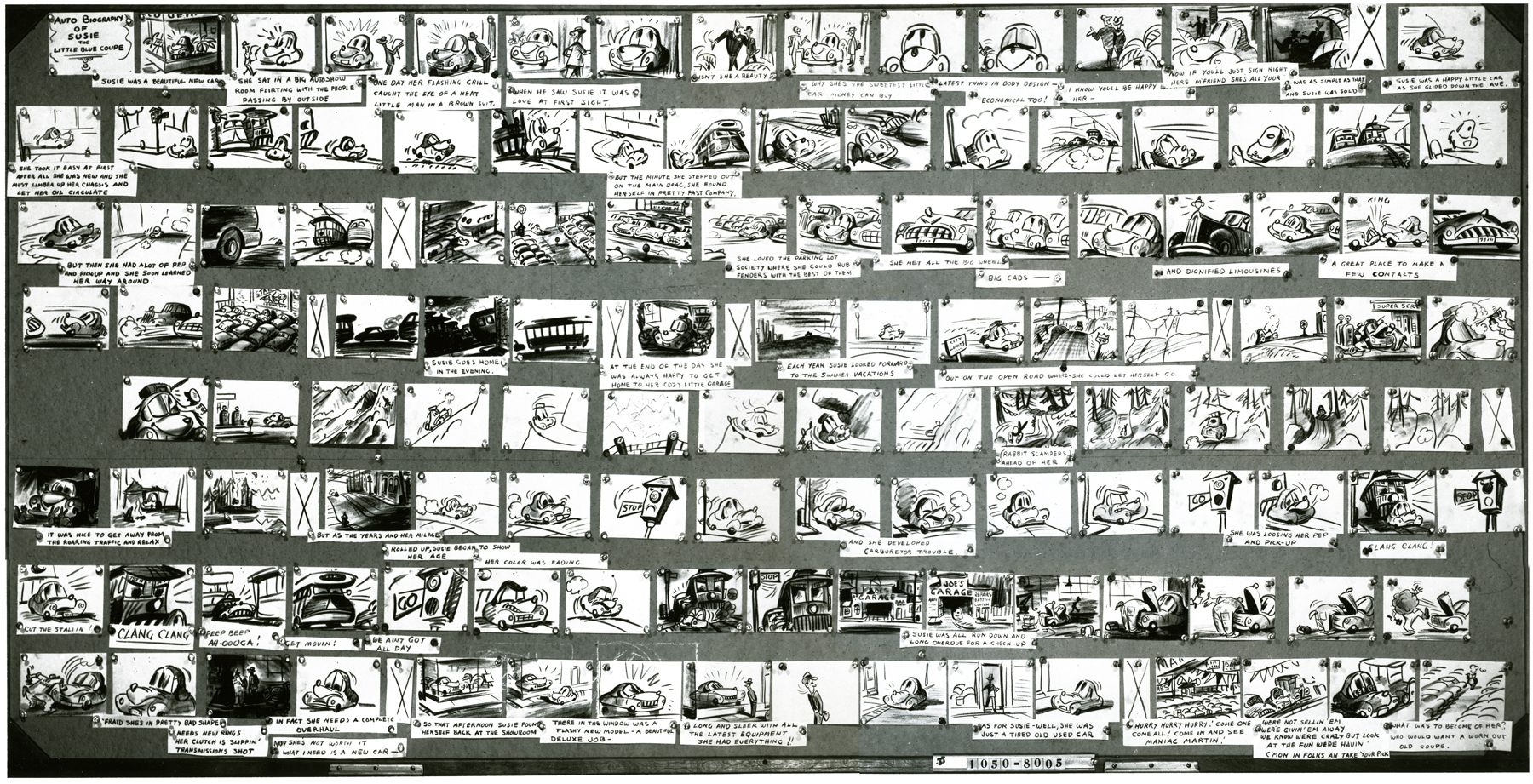

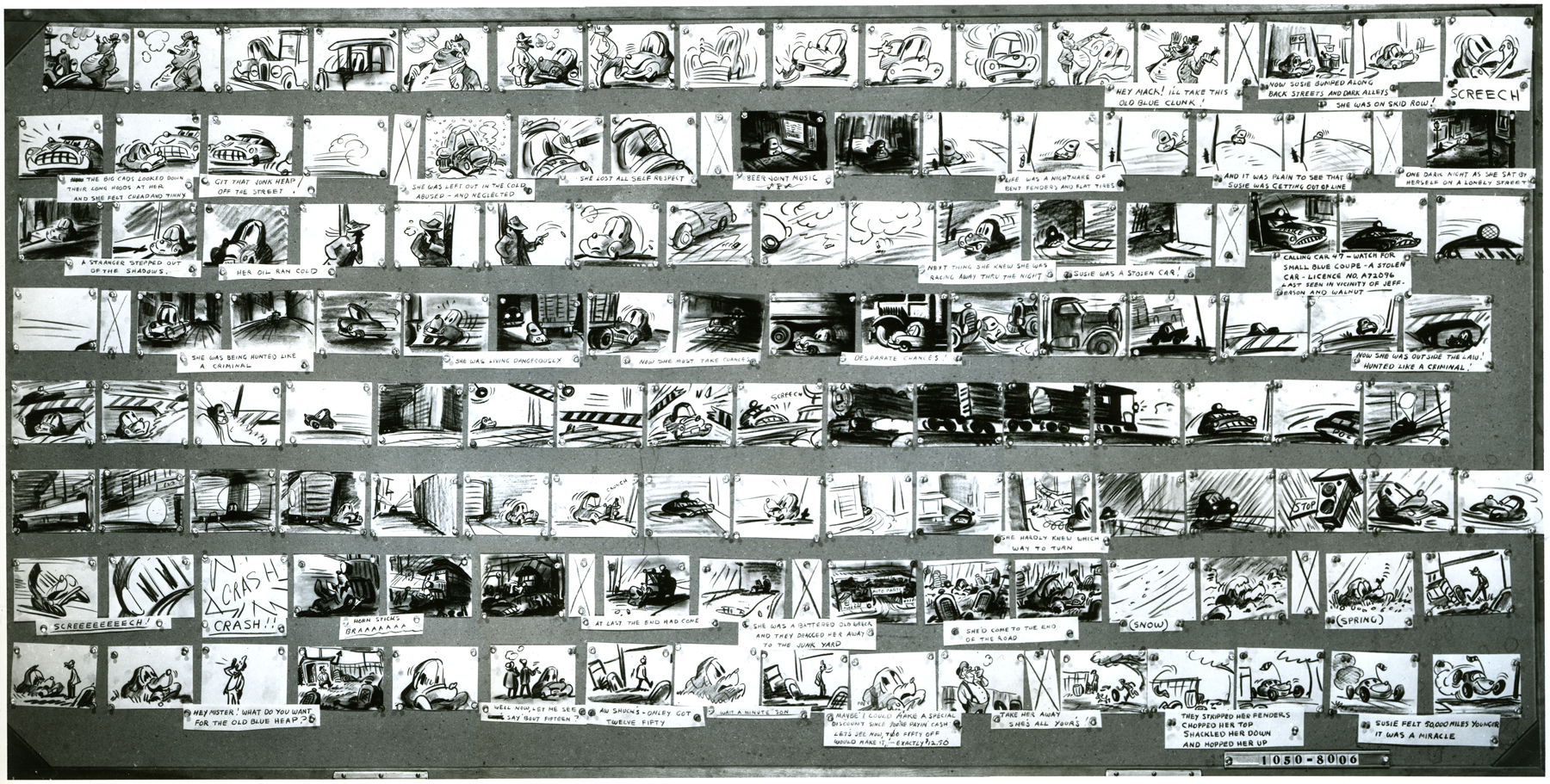

Bill Peet's storyboards for the 1952 Disney short "Susie The Little Blue Coupe":

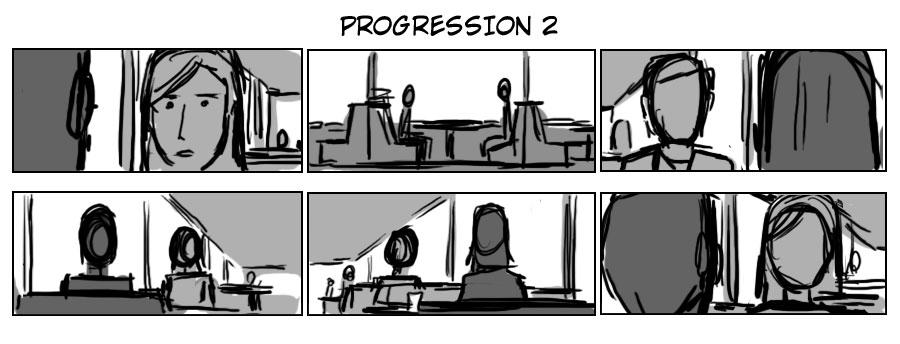

Shot Progression

Take a look at progression number one, six shots of a couple talking in a restaurant. It's a basic progression that starts far away and neutral and ends up in an extreme close up featuring one character. The script may start out with some chit chat between the characters, and intensify to where in panel six the woman makes an important statement (ie: "I'm pregnant," or "I'm leaving you", or even "oh crap-- I left the oven on" etc). For all intents and purposes, this is correct. The shots slowly intensify to a visual climax.

Now look at progression 2; same six shots, but they've been jumbled around. For the script we're using in progression one, this would be considered wrong. The shots are all over the place. Sure the woman could say "I'm leaving you " in the close up in panel six, but what impact will it have after the extreme close up in panel one? How is it building intensity if we're going to a wide neutral shot, then close up , then out to medium shots?

Now the tricky part. With a different script, the second progression could work. Say the woman gets a phone call (before this scene) from the man and he says "Sally, the money's gone; meet me at the cafe".

With that intro, the script for progression two may go like this:

panel one: (woman) "what do you mean the money's gone?"

panel two: (man)(looking around nervously and whispering) " I don't know, the suitcase was empty"

panel three: (man) "we've got to find that money"

panel four: (woman) "all right but being here is making me nervous, they could be following us"

panel five: (man) " what do you think we should do?"

panel six: (woman) "we need to get out of town"

The most important bit is the woman's reaction to the money being gone and the ECU opens the scene with a punch. The second biggest bit is "we need to get out of town", so that gets a close up in panel six although not as big as panel one. The lines of them talking about being scared of being followed are in wider shots to emphasize the people around them and that they're in a public space.

This is a simple way to illustrate that a progression like number one, (although visually solid) isn't always the right one. When you are storyboarding, keep in mind that your shot progression will depend on what is happening in your scene. Make sure your shots best emphasize what's transpiring in the story.

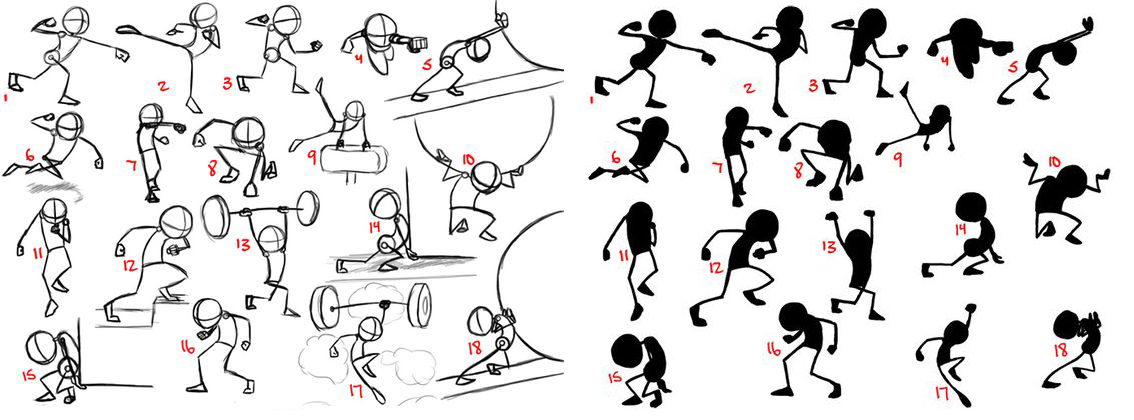

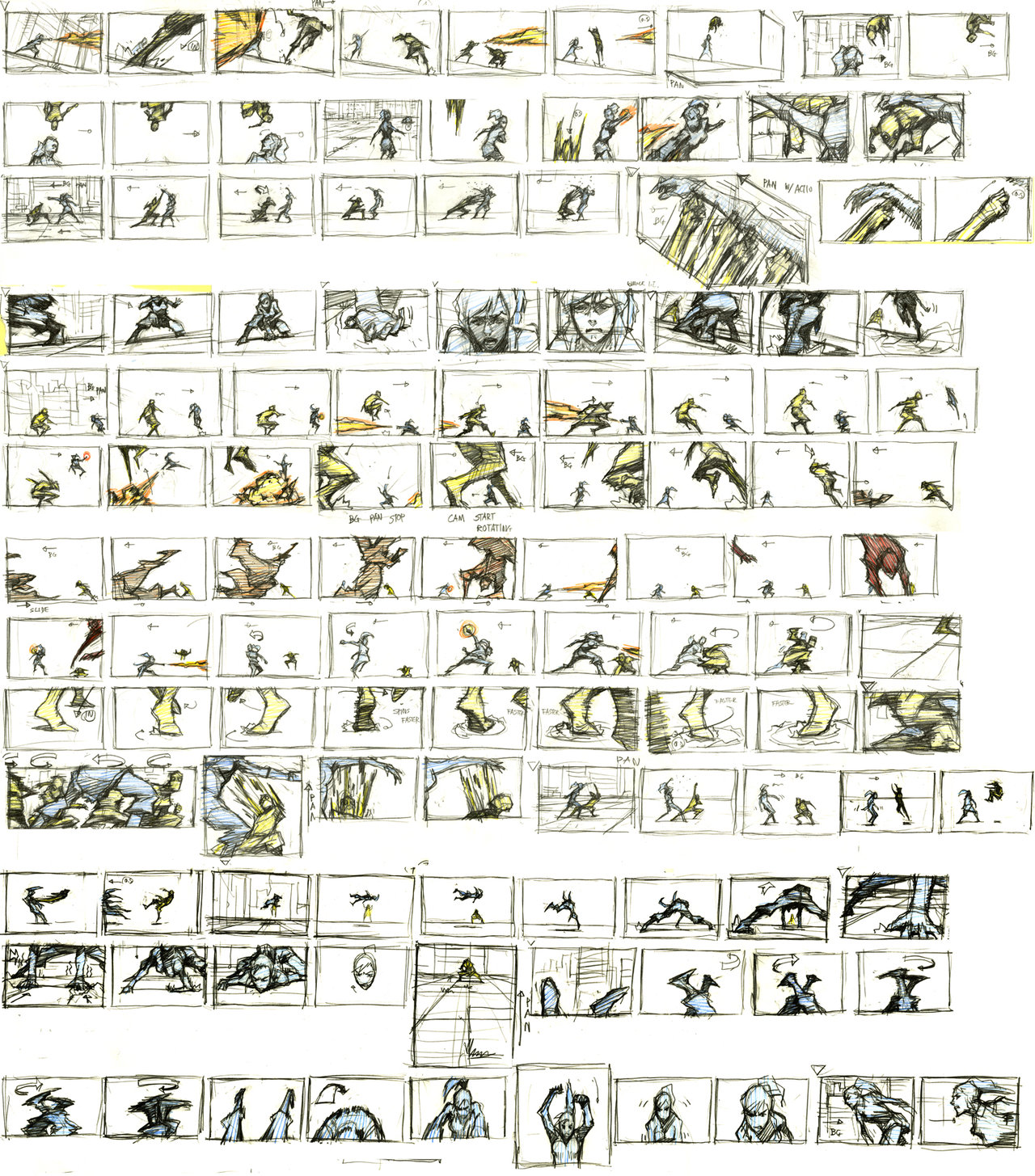

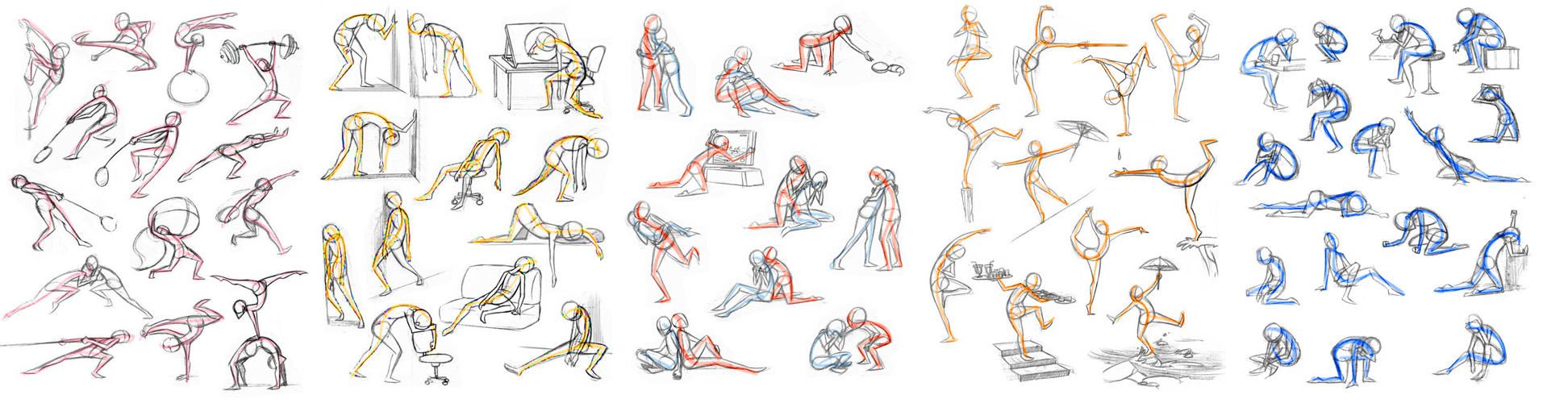

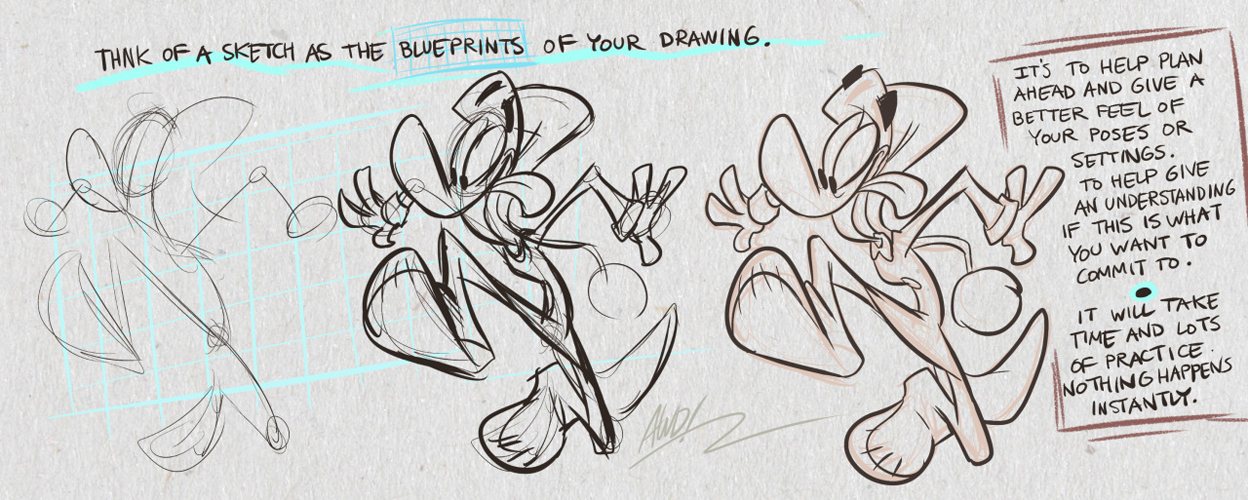

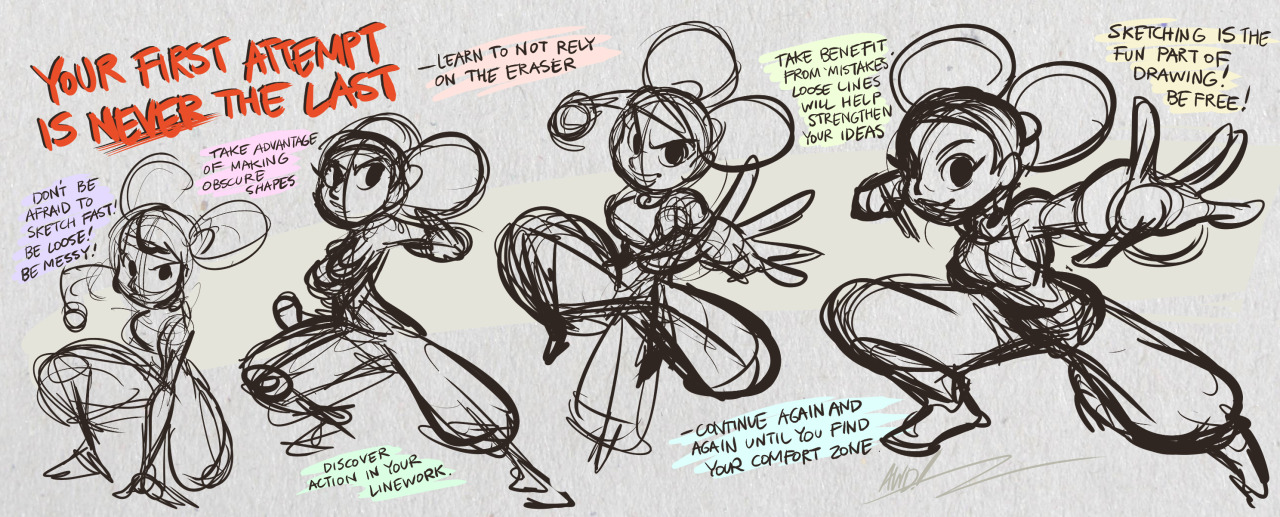

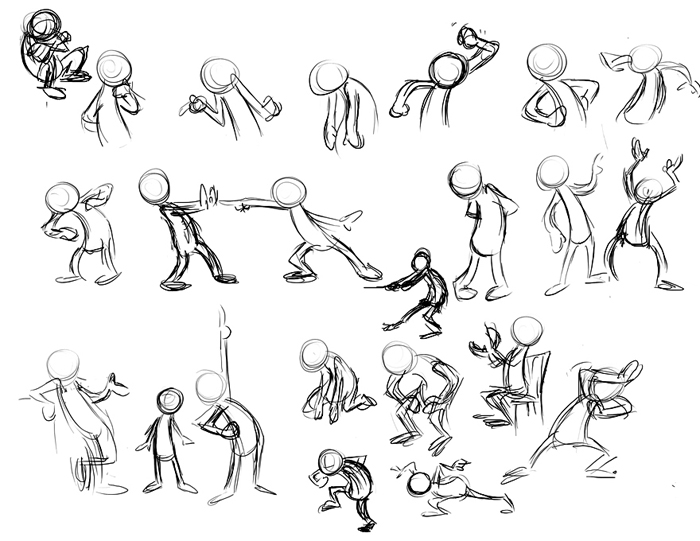

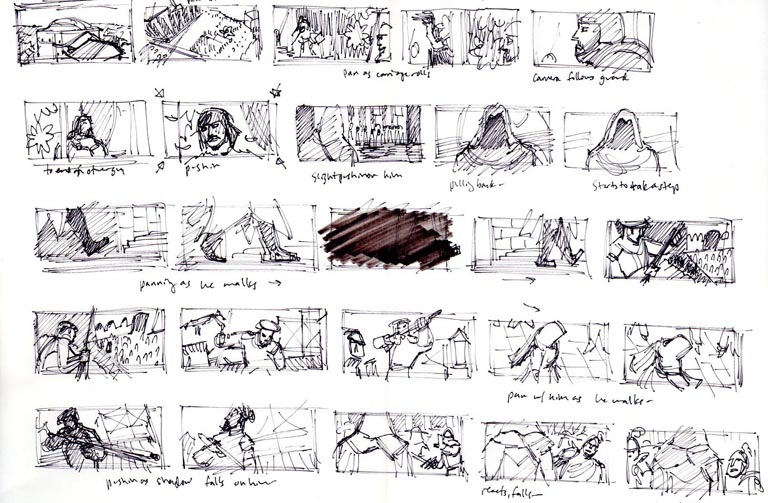

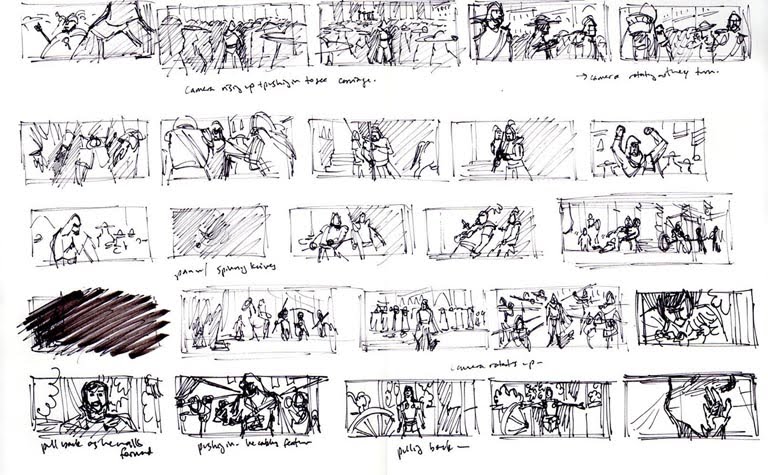

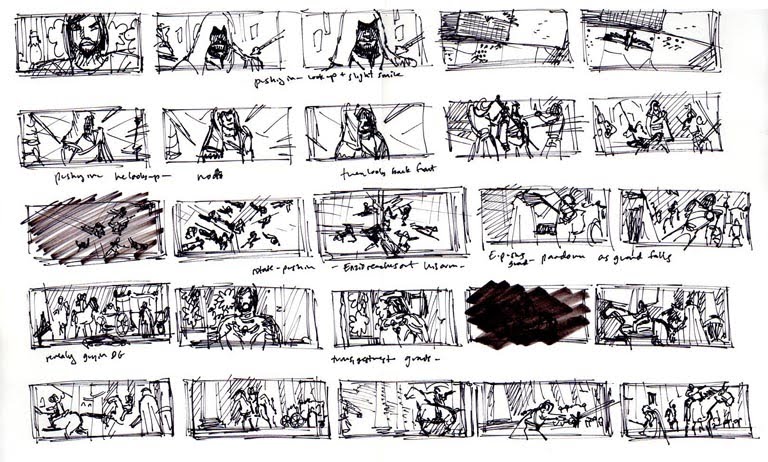

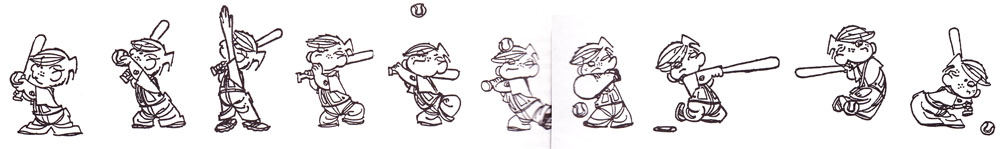

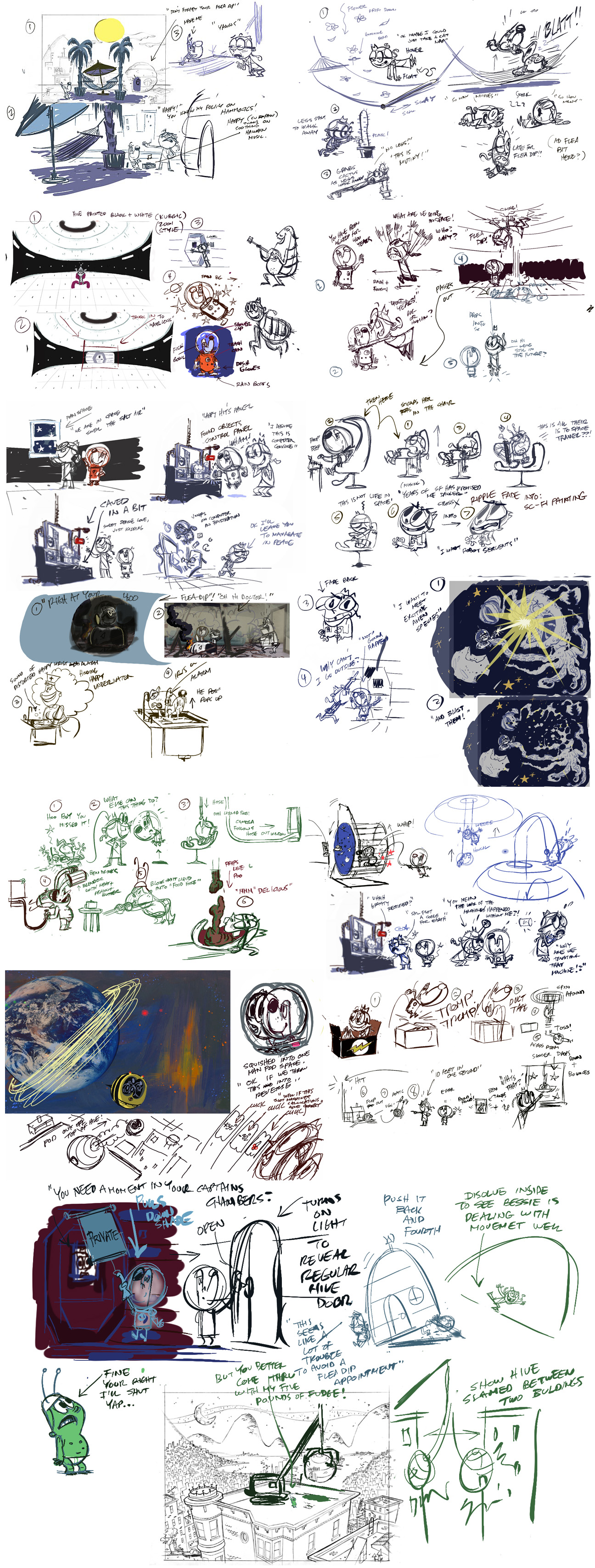

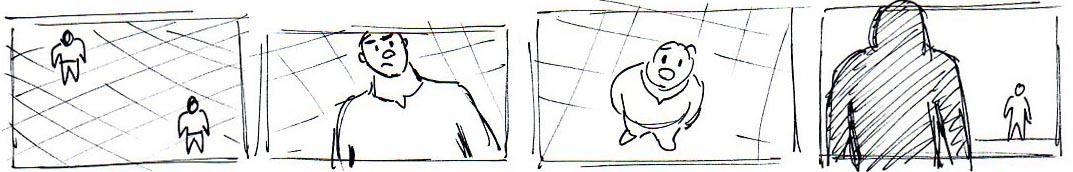

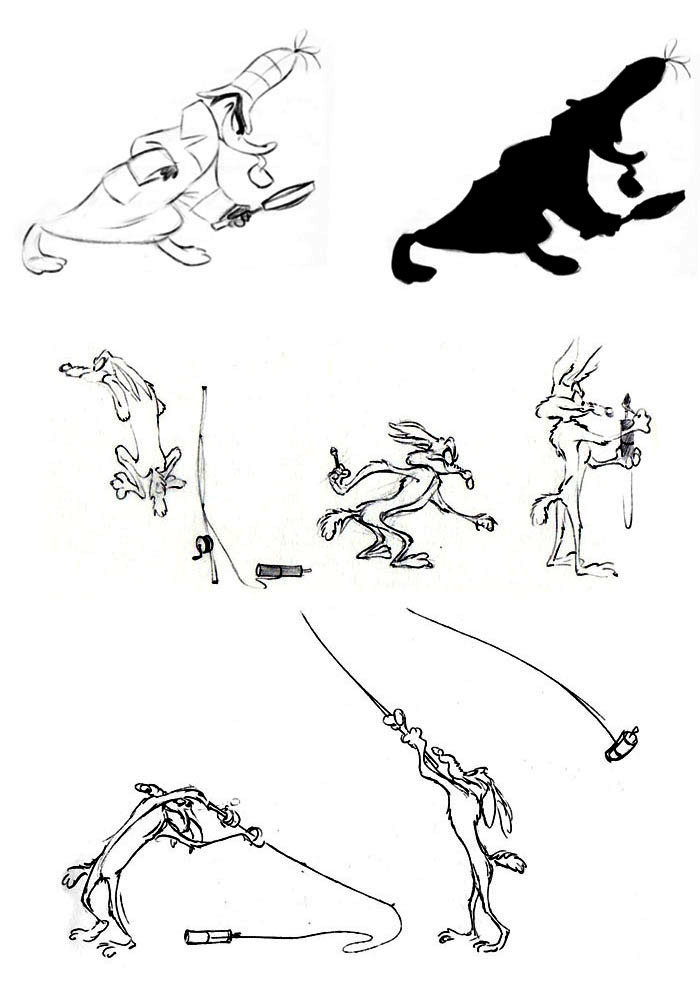

Thumbnails

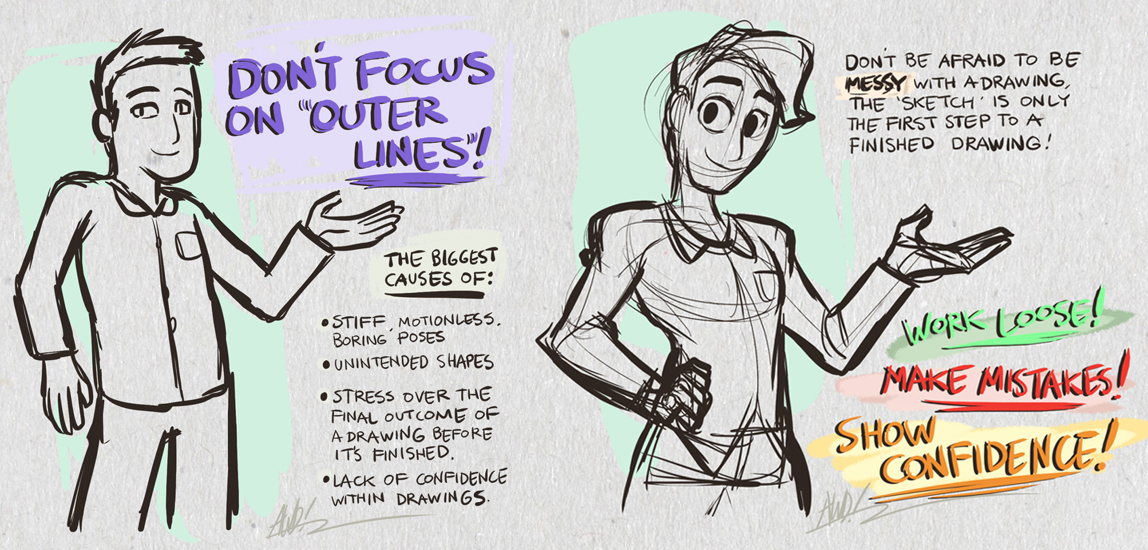

We use thumbnails to work through our ideas. To get past our first ideas (remember - your first idea is always the worst and most

cliched idea. The first idea you think of is probably the first and most obvious idea that the audience will think of too!), and get on

to the ideas that count. The later ideas will be the good ones. They'll be the most inventive ideas, and the most original. But to reach

those ideas, you'll first have to work through the cliched ideas, right?

Thumbnails are, without a doubt, the fastest way to do that.

The quickest road to a great idea, then, is through thumbnails!

When you get a new scene, sit down and start doodling. Maybe it's just poses. Maybe it's working out full actions. Either way,

you're quickly discovering what will work and what won't, and it's all on paper. Quick and dirty - that's the way to do it. Even use stick-man for your characters. Many of the best animators do their thumbnails with what is essentially a stick-man.

As long as you can see where the

character's hips are, the angle of the hips, the angle of the shoulders, angle of the head, the position of the limbs, and the placement within the frame - that's ALL you need to know at this point, and you shouldn't be worrying about any other details yet, generally speaking.

Remember - They are SUPPOSED to look rough. They are not meant to be pretty pictures. Don't spend or waste a lot of time making each thumbnail

look like a piece of art. Don't waste time shading it in, drawing all the little details, etc. They're meant to be fast and sloppy. The entire

point of doing thumbnails is that it saves you time.

How does it save you time? Well, if you do thumbnails as part of your planning process, then you can work through all of your ideas

BEFORE sitting down in front of the computer, and it's inarguably much faster to doodle a little stick-man doing a pose than it is to

pose him out in the computer.

So, the first rule is to stay rough, and the first *use* of thumbnails is to discover the best ideas for your shot.

The second use of thumbnails is to get fast feedback.

You can save yourself days of work (and a great deal of frustration) if you run your thumbnails past your lead or your director before

diving into the actual scene. Nothing is more frustrating than spending 3 days blocking in something that you think is great only

to find out, once the director gets a look at it, that you're doing something he doesn't like at all. It's always a great idea to run your

thumbnails past them first, so you can save yourself the headache (and heartache!) of hearing the dreaded "start over" words from

your director.

Here's a

few quick methods for producing fast and dirty thumbnails.

2. Copy up a set of storyboard sheets so you don't have to spend all night drawing screen boxes.

3. Sketch in pencil so you can make changes easily, then use markers for photocopying. Feel free to use any medium you are happy with - professional storyboard artists use everything from magic markers to charcoal.

4. Scribble down short notes about what's happening in shot and what characters are saying.

5. An overhead plan view of the location of the camera, actors and props can be helpful if you know the environment you are going to be working on.

6. Number your shots so that they can be quickly referred to on the shot list, during editing, or when you are pitching the boards to someone.

![]()

Drawing storyboards is an excellent way to keep motivated, to show you're organized and to let everyone else know what's going on in your head.

In Live-Action, storyboards

aren't there to constrain you. Just like the script they are there

to back you up during shooting. If everything starts flowing on set let

it happen. In the real situation you may see a new angle - go ahead,

shoot it. Get the shots you need by checking your storyboard and give

yourself the time and freedom to experiment.

In animation, a good way to thumbnail out some ideas is by doing a 'Beat Board'.

Beat Boards are sketches for the storyboard artist made to help them with gags, posing, stage direction elements and in some cases even art direction & layout.

Usually these are sketches that help to explore ideas about how to plan out certain shots.

Beat boards by Bill Wray:

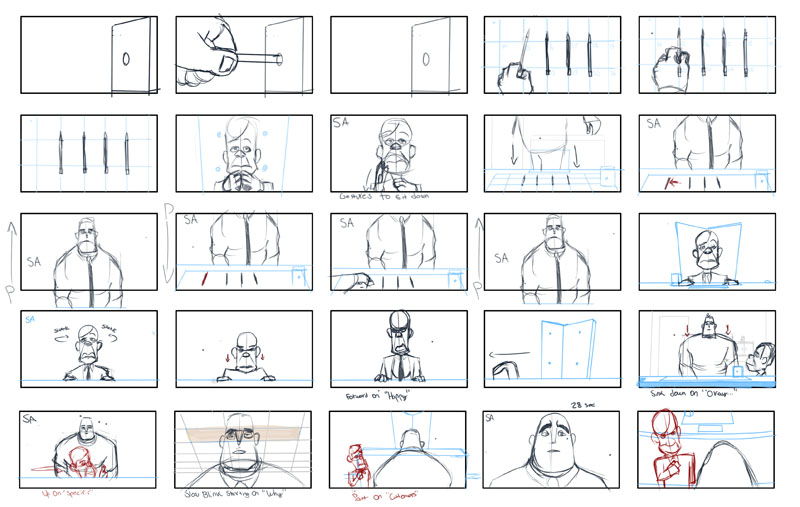

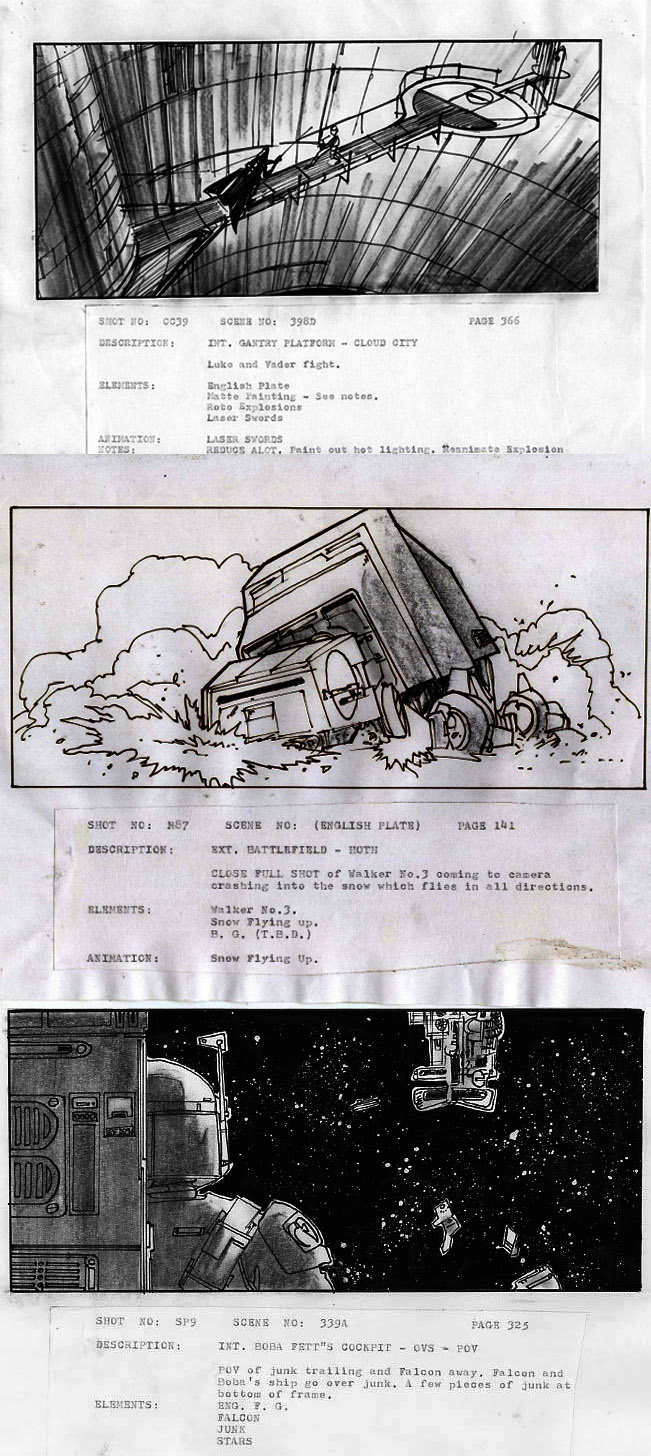

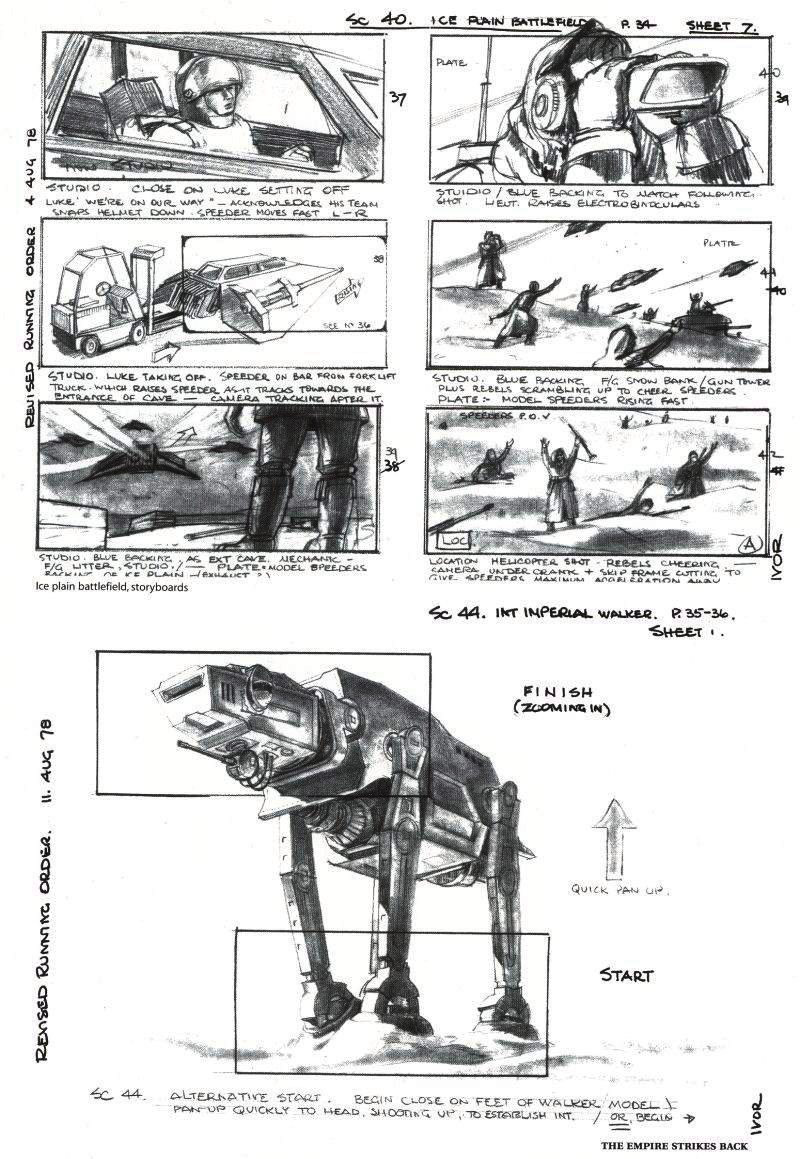

Storyboards can be very detailed or very simple, they can have lots of panels for every shot to map out and choreograph the movement, or they can be very general - made to only capture the angle and composition of the shot.

One of the ways I like to study, is by printing out a picture I like. I then take the time and trace over it. Now at first this might sound like a big waste of time but it isn't. Sometimes the mind seems to trick us into thinking a certain line or shape is different than exactly what you see in front of you. We sometimes see what we want to. So with having the added sense of feeling, of going over the same lines that are there, you are able to see and feel the shape, length, direction, thickness, rhythm of each line. You will start to feel the design. You are adding another sense while studying.

It's kind of like what a blind person would do when they touch things. They are using the sense of touch to see. Well when I trace over a picture, I get that added help of seeing by feeling the drawing as well. My drawing skills grew when I started doing this. So don't be embarrassed to trace over things, you will learn a lot.

Animation Master Glen Keane, once said "if you are drawing a blank, or are having a hard time drawing a certain thing, then it is because you have not studied it enough". You can only draw what you know. Sadly there is no magical dust (believe me I have tried searching for the stuff) that will make you a better artist. The fruit of great art comes from the roots of studying, observation, and hard work.

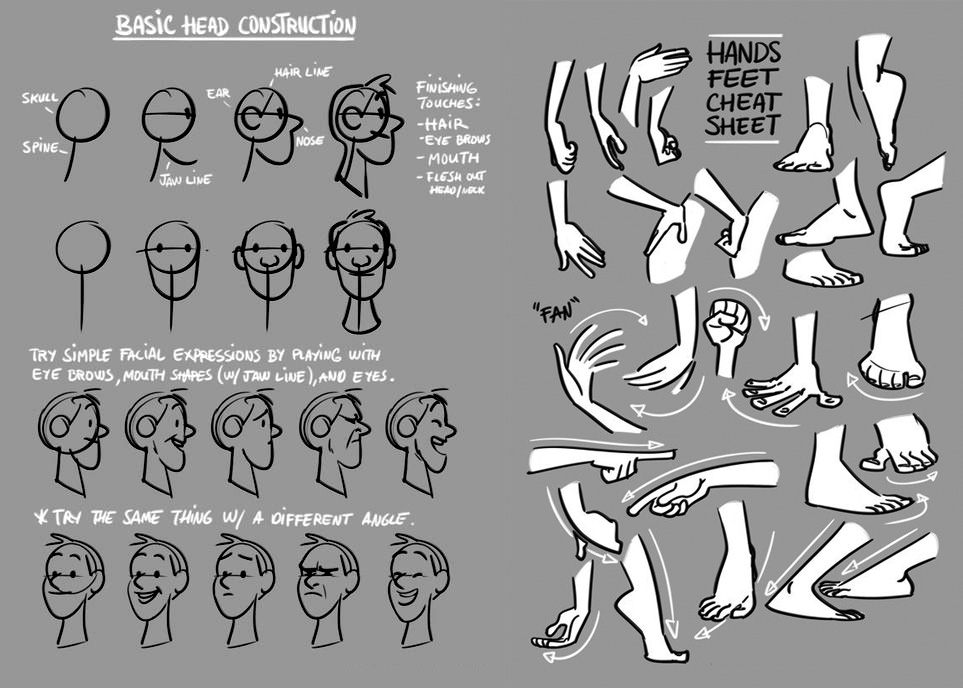

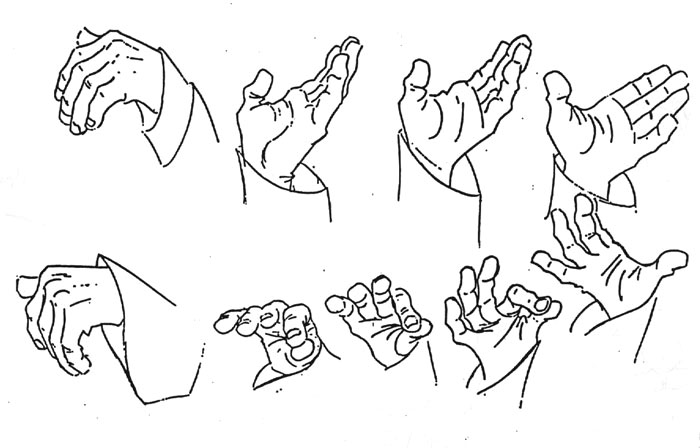

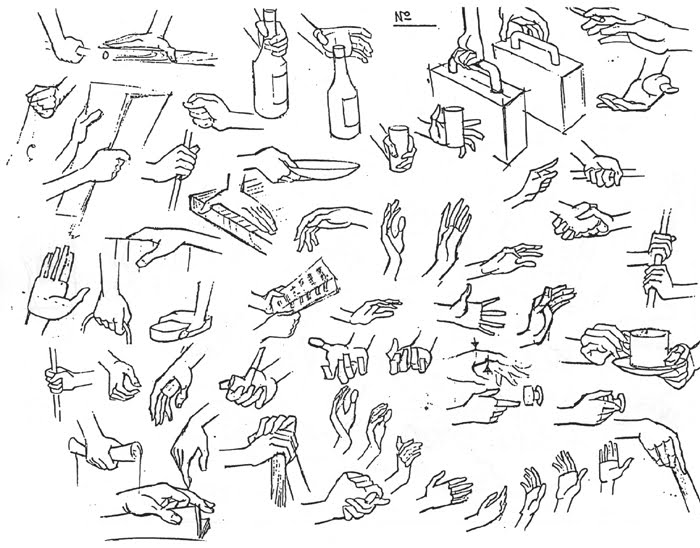

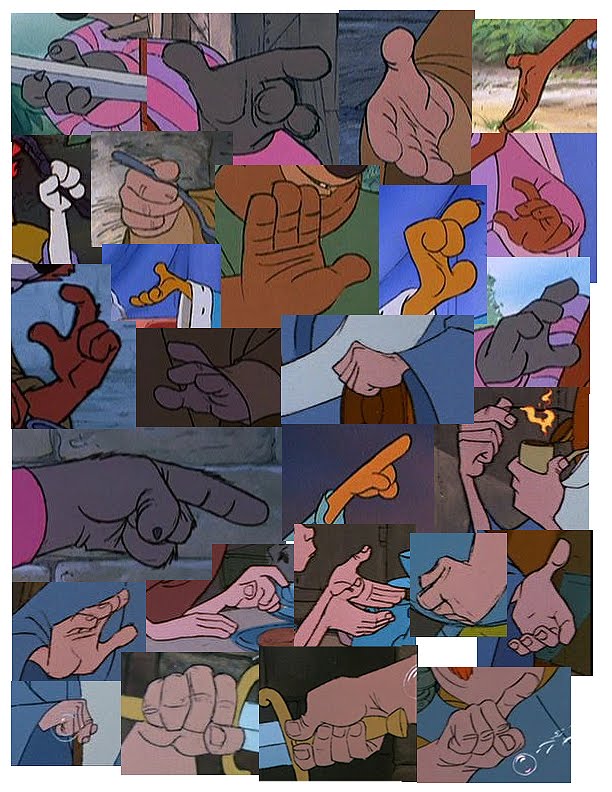

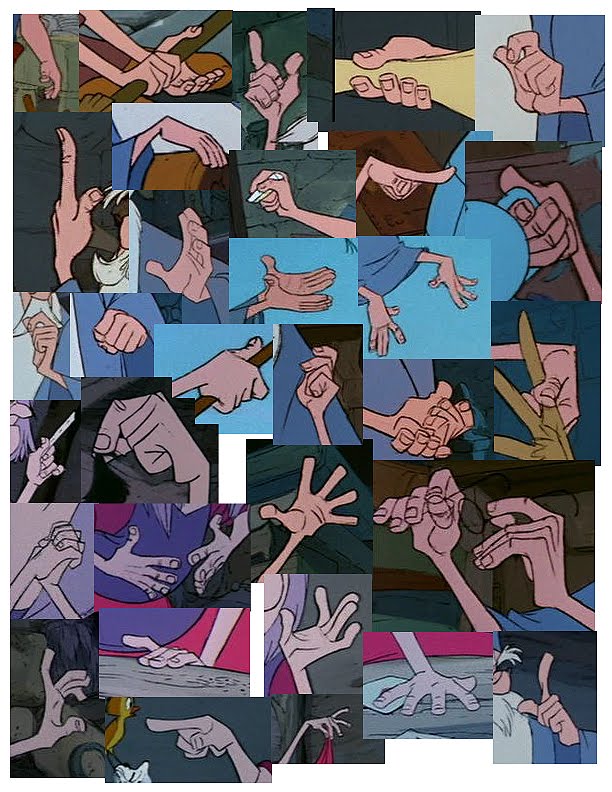

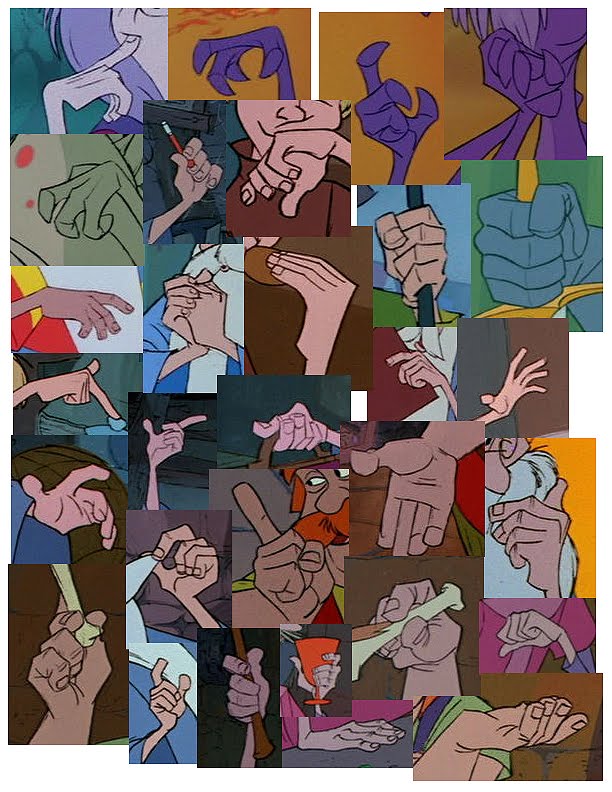

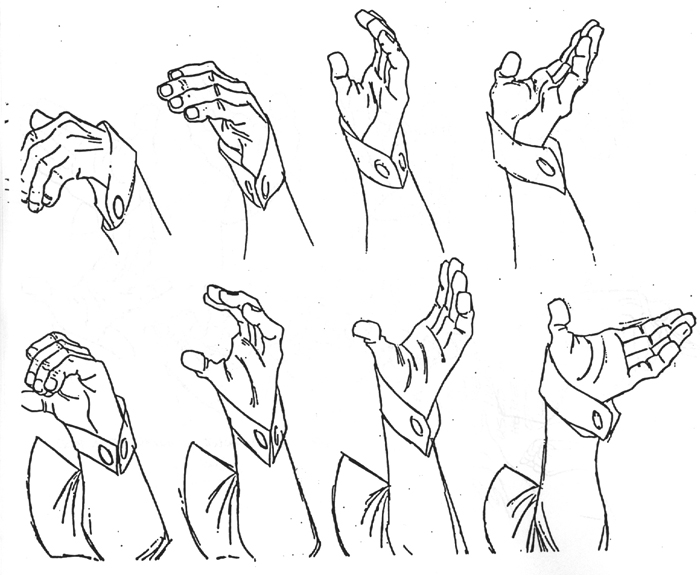

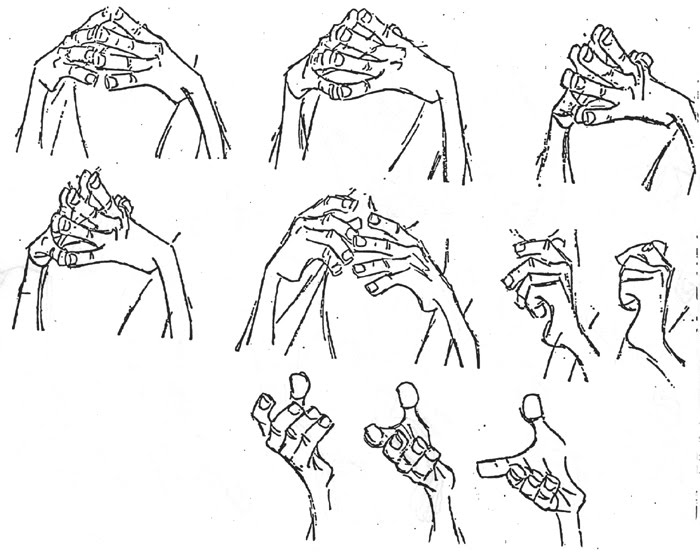

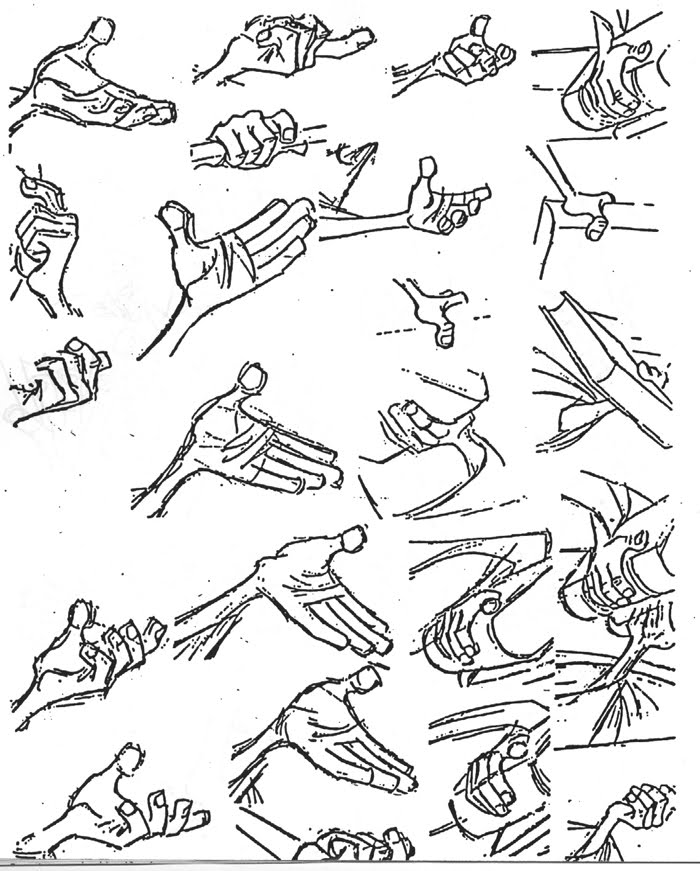

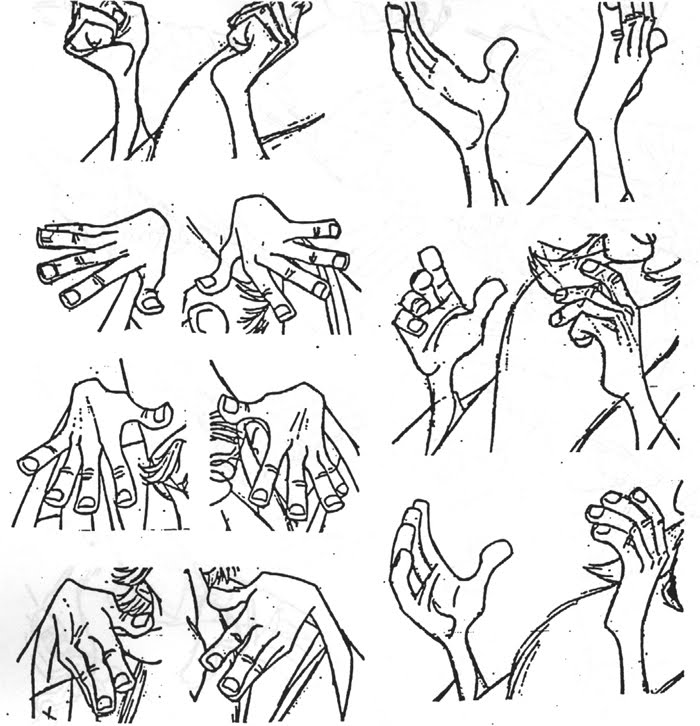

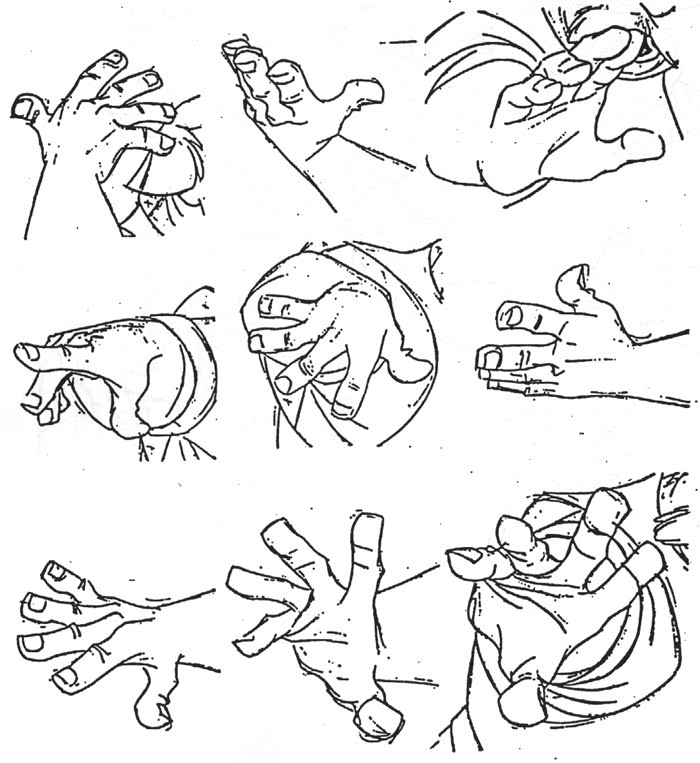

So for people like me that have a hard time drawing hands this is the type of (great) artwork I would printout, trace, study, and observe.

Do this for all aspects of art that you have difficulty with.

Plants, buildings, mountain landscapes, people's feet, cars, whatever it may be... find references, trace over it over and over again, this will increase your draftsmanship skills and thus make you a storyboard artist.

>>>>

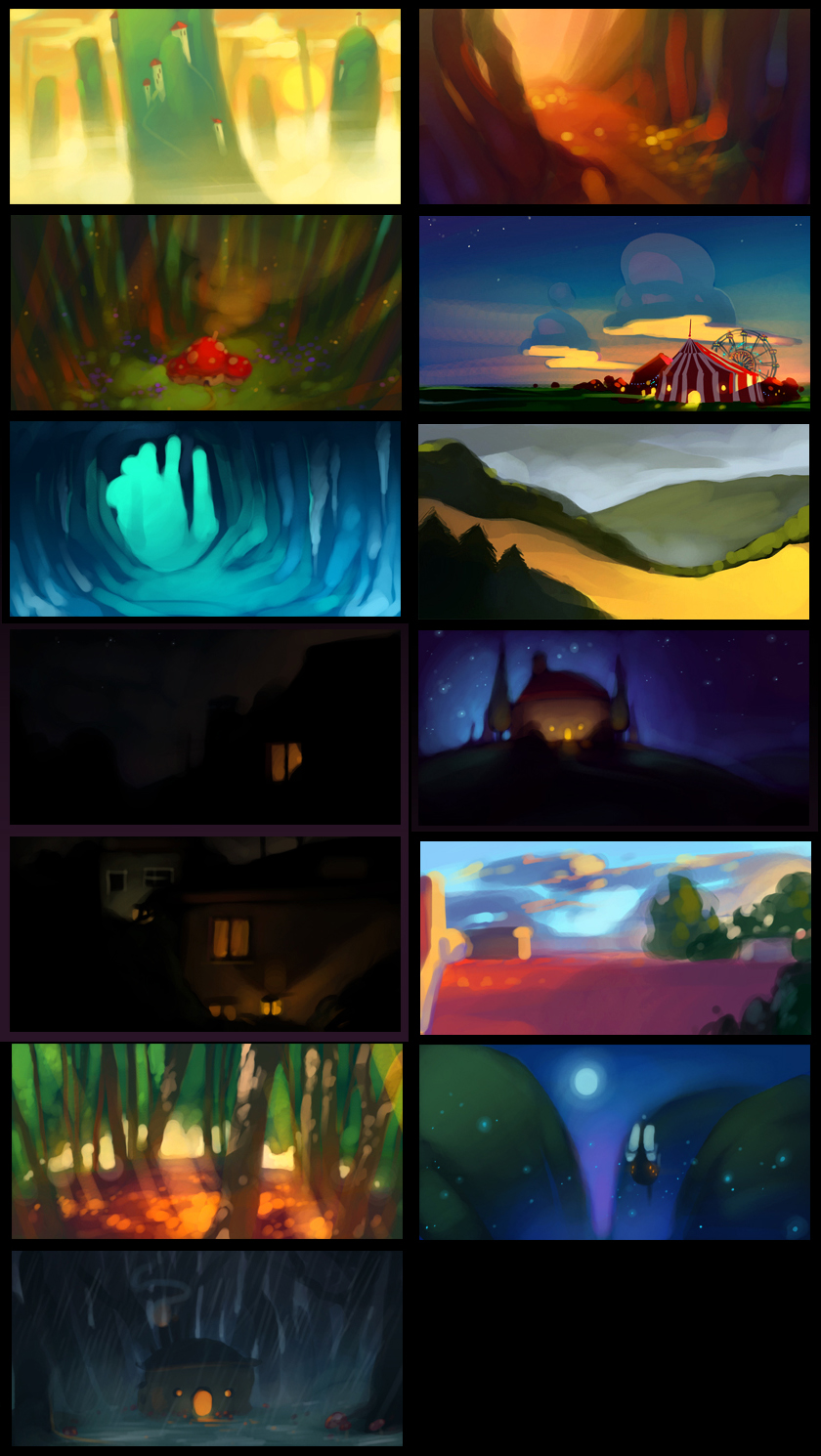

For every Pixar movie, a color script is created, which is essentially a rough look at the color keys, palettes, and tones for the entire film. A color script gives you a good look at how the color arcs in a film relate to the story. Lou Romano created the color script for Pixar's Up. It's done after the screenplay and designs are complete and it's an overview of the entire movie.

"The Incredibles" Color Script:

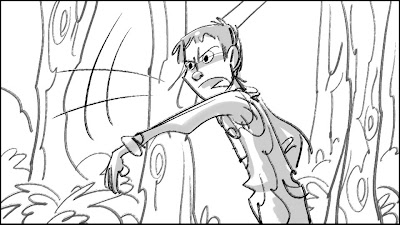

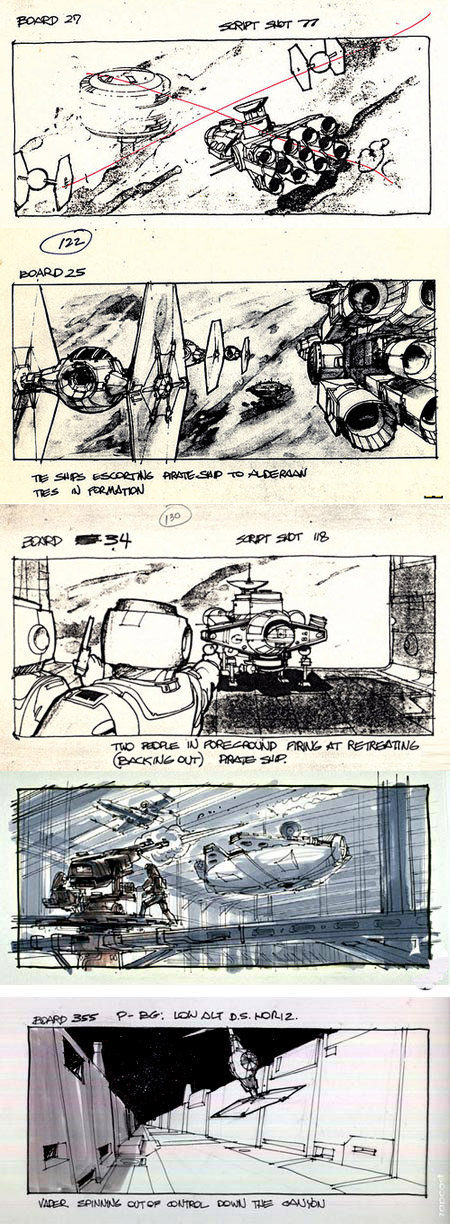

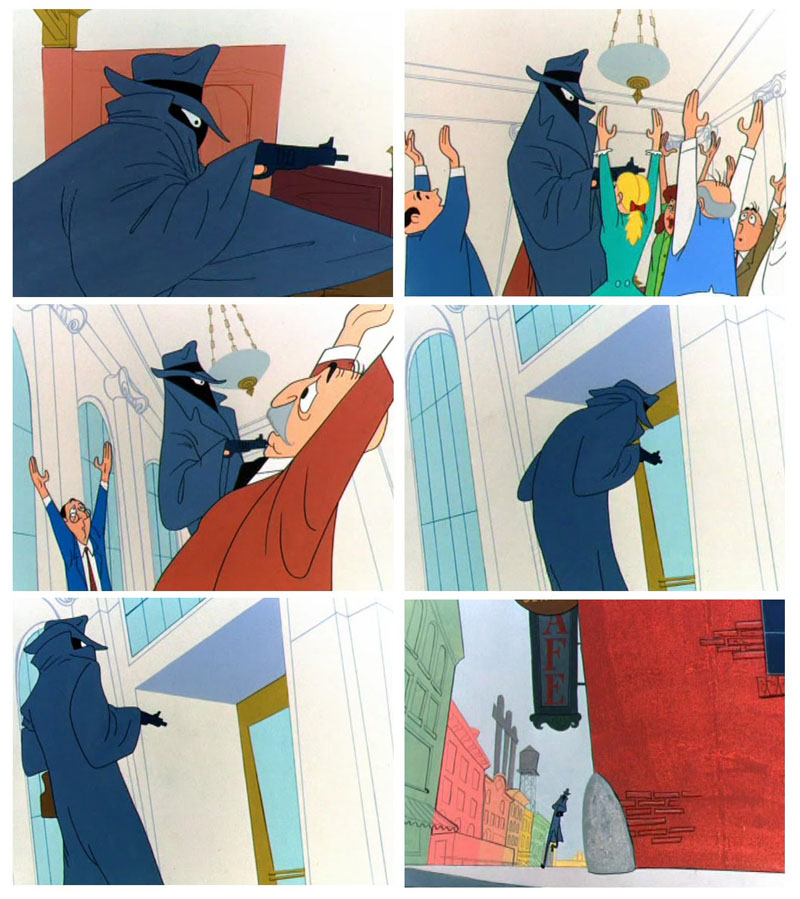

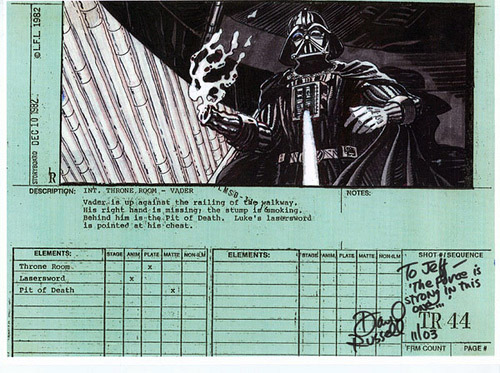

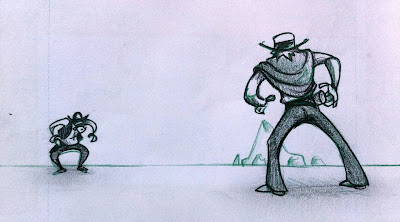

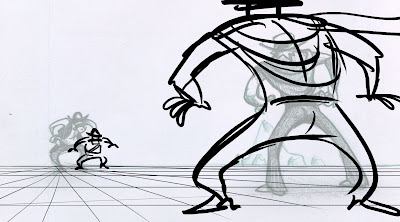

So I redrew the layout to express this feeling. I placed the little guys lower in the frame, and I launched the masked man up high - utilizing a low camera angle - a classic and cliche way to make a character more powerful (just look at all the low shots of Darth Vader). A bonus to the scene now is that I can show some really frightened expressions on the little guys.

So I redrew the layout to express this feeling. I placed the little guys lower in the frame, and I launched the masked man up high - utilizing a low camera angle - a classic and cliche way to make a character more powerful (just look at all the low shots of Darth Vader). A bonus to the scene now is that I can show some really frightened expressions on the little guys. The re-staging of this shot even influenced the style of drawing... I drew the masked man in the improved version with a lot more insidiousness and evil... whereas the previous version, the masked man comes off as a bit too cartoonish, and the overall composition improved as well. I suppose this is just a reminder to push yourself at every level... you just never know how you can improve your shot, so experiment with angles and depth.

The re-staging of this shot even influenced the style of drawing... I drew the masked man in the improved version with a lot more insidiousness and evil... whereas the previous version, the masked man comes off as a bit too cartoonish, and the overall composition improved as well. I suppose this is just a reminder to push yourself at every level... you just never know how you can improve your shot, so experiment with angles and depth.

Observe the clear staging practiced by Chuck Jones in "Baby Bugs Bunny" (1954)

Always search for and study great composition!

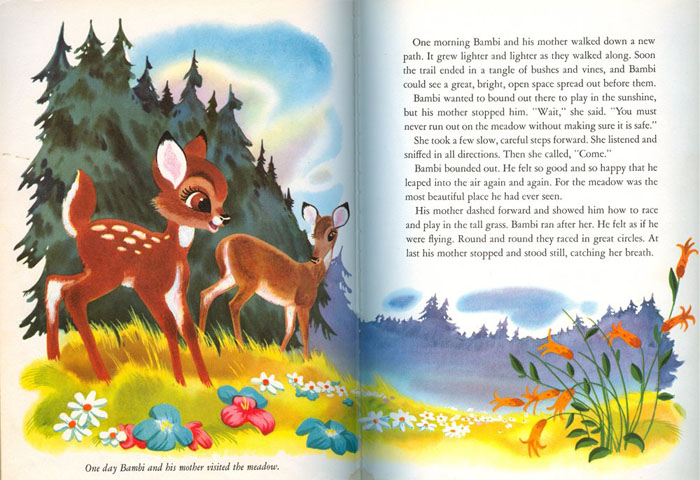

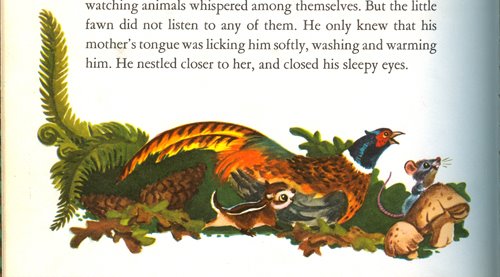

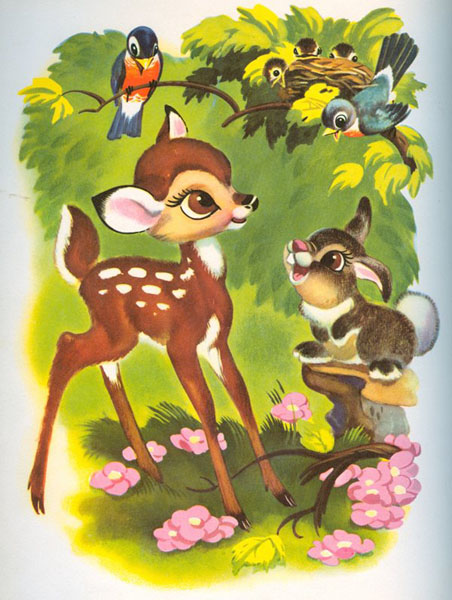

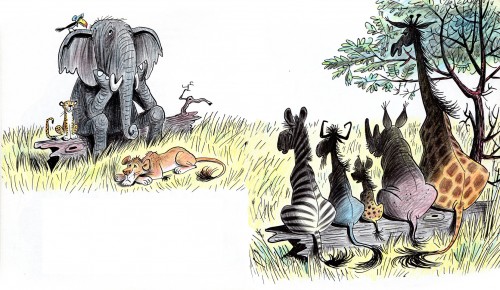

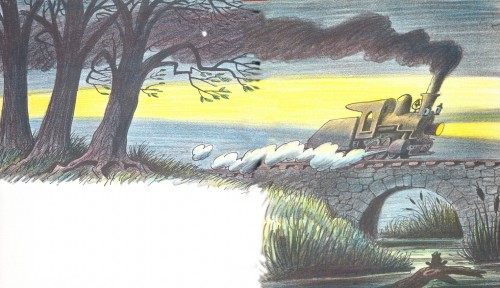

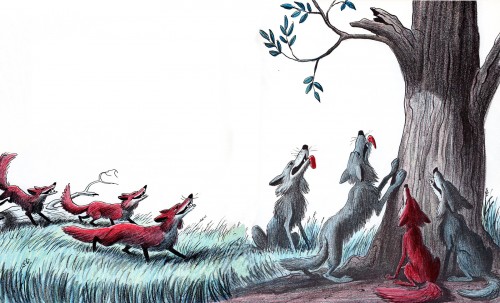

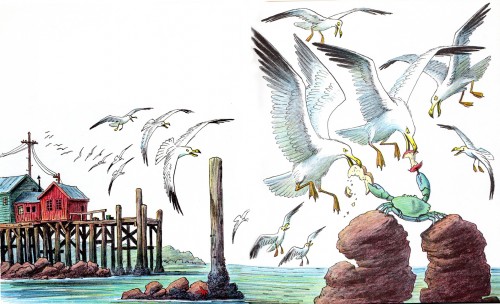

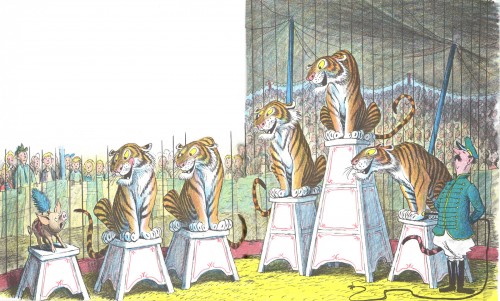

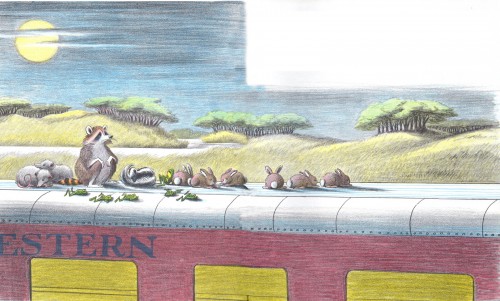

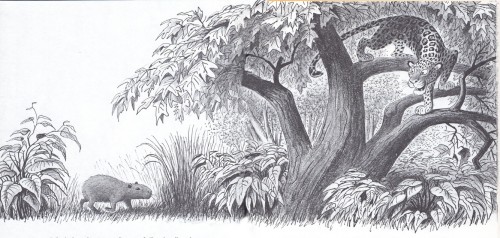

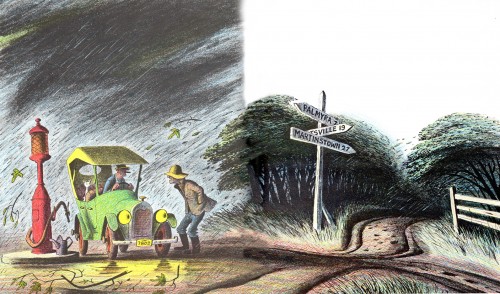

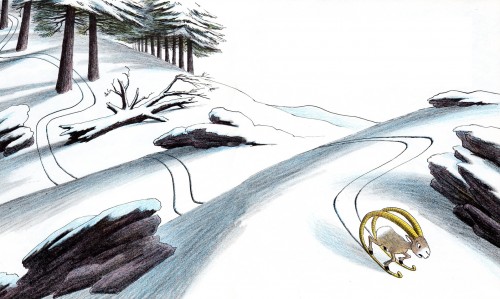

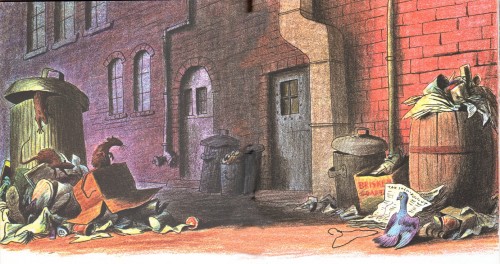

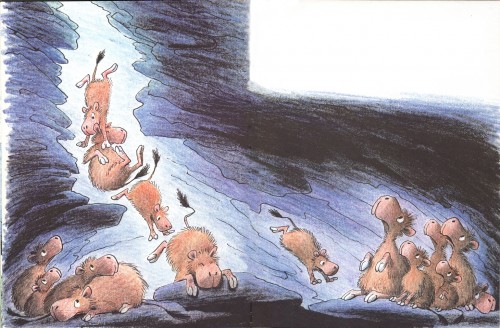

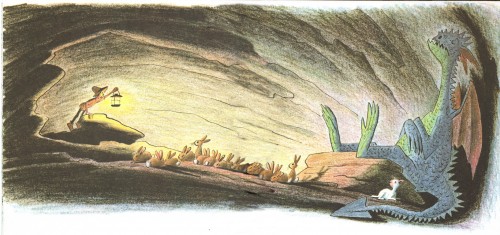

Study the works of the Godfather of Storyboarding - Bill Peet, here are samples of his Children's Book Illustrations:

Observe the power of the pyramid.

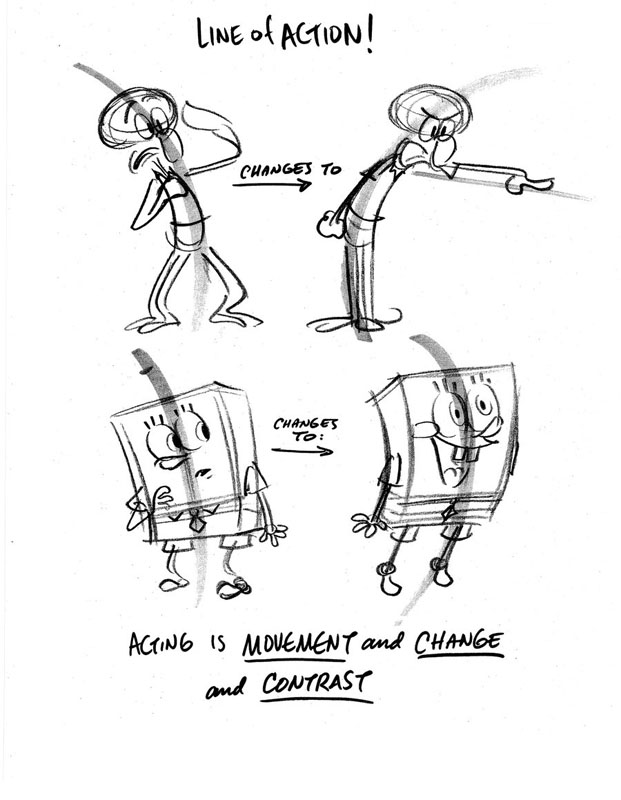

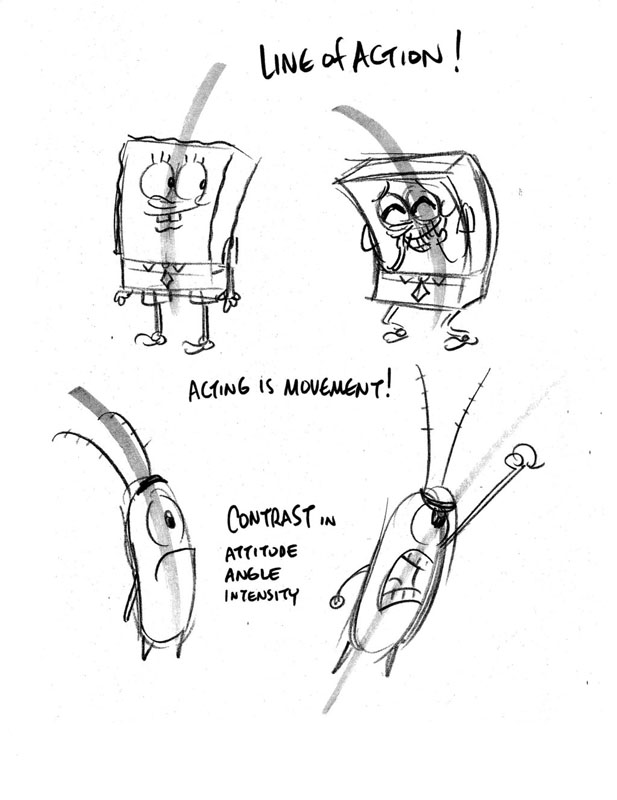

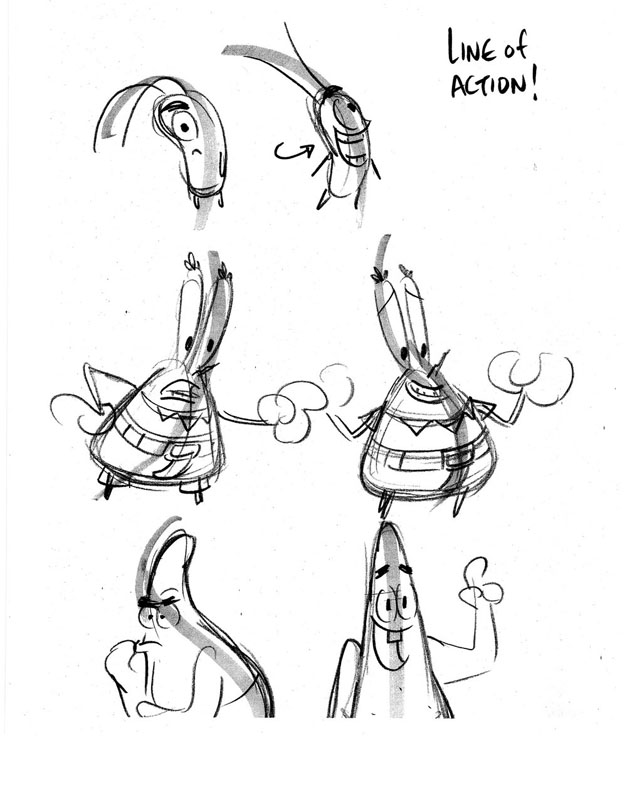

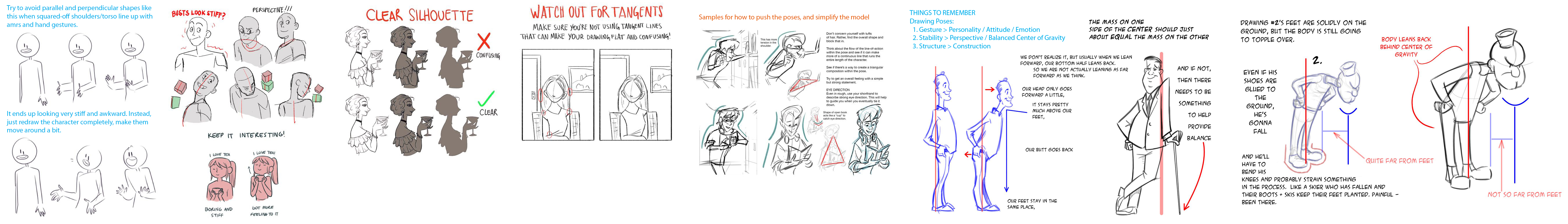

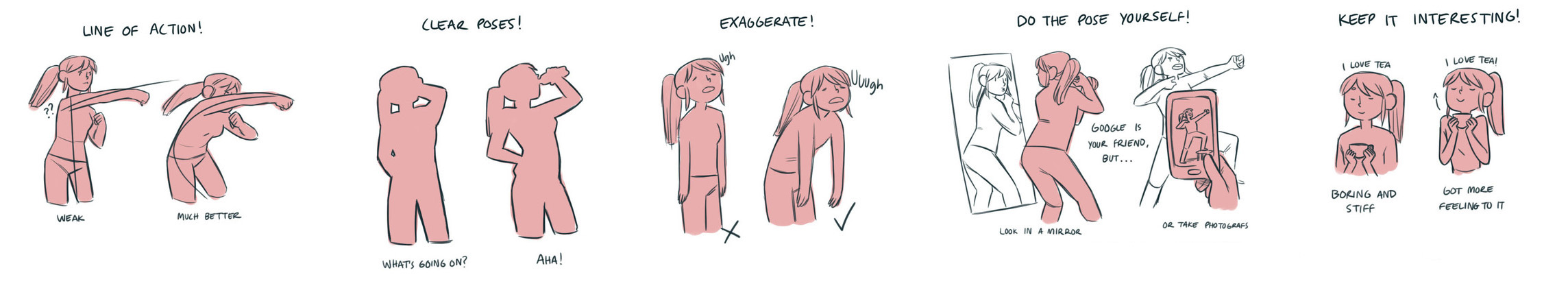

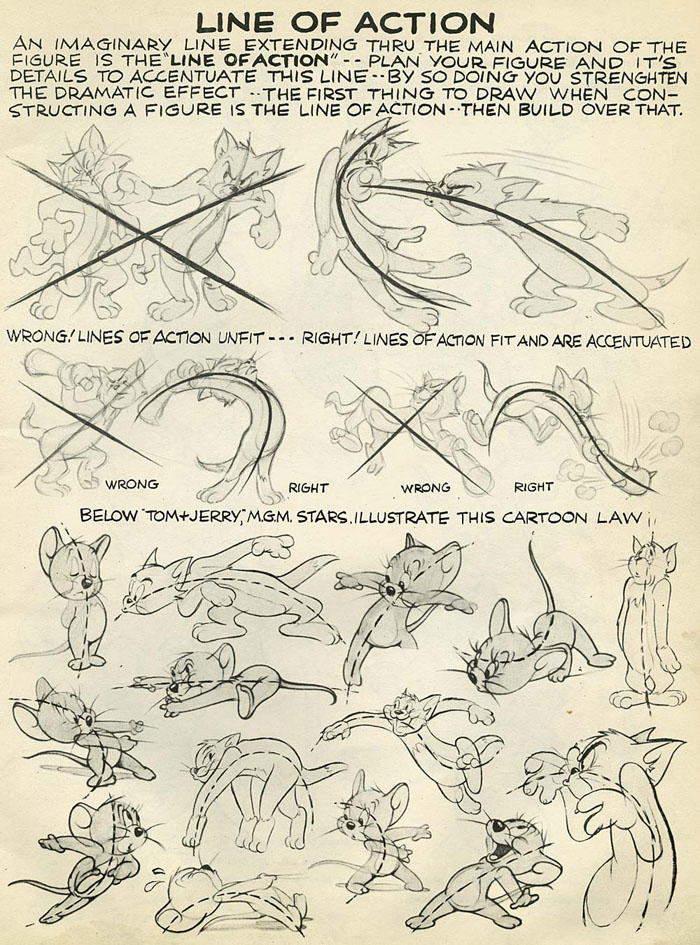

We all know about "poses" and "lines of action" and their massive importance in storybaording, but another aspect you should include in your thought process is the idea of creating solid shapes.

There is a very common shape that we all use often - the curve. Its nice to contrast between backwards and forwards curves in our poses, and also straights against curves. These are still lines (but not necessarily "lines of action"). One particular shape that you will notice in many great photographs, illustrations, paintings, comics and animation over and over again to help define strong poses and dynamic forms - is the pyramid.

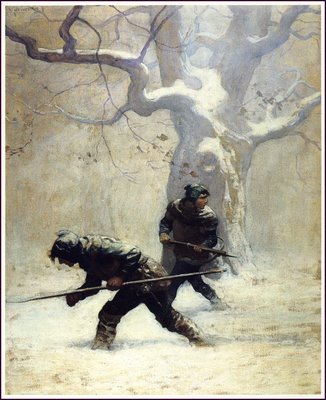

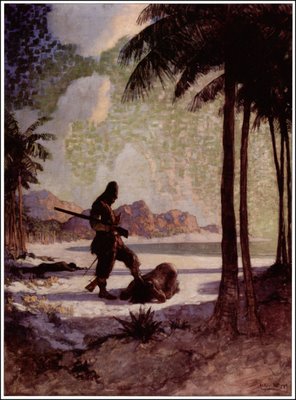

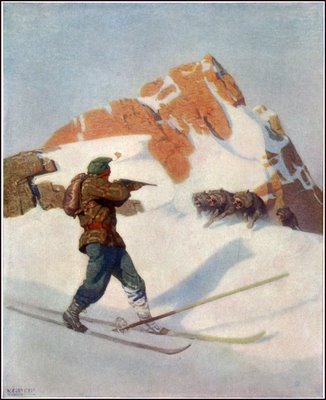

Look at these samples, and see where the triangular shapes can be found everywhere, and how they can create dynamic forms and intersecting lines to show power, weight, balance, stability, or elegance, while adding angles and contrast to any opposing forces within the image.

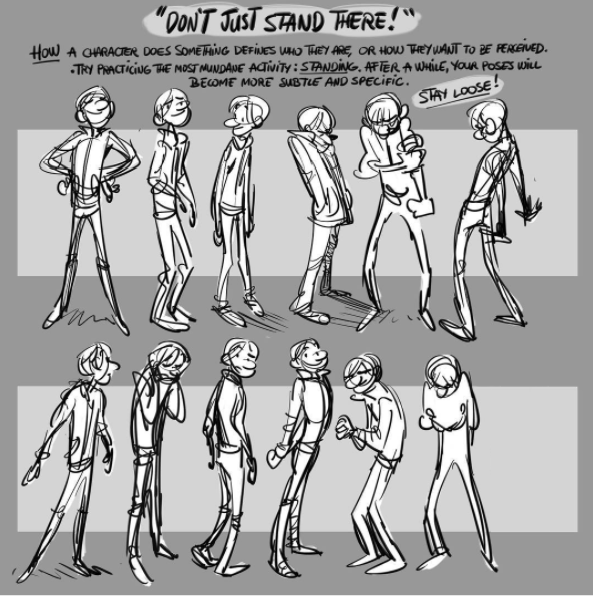

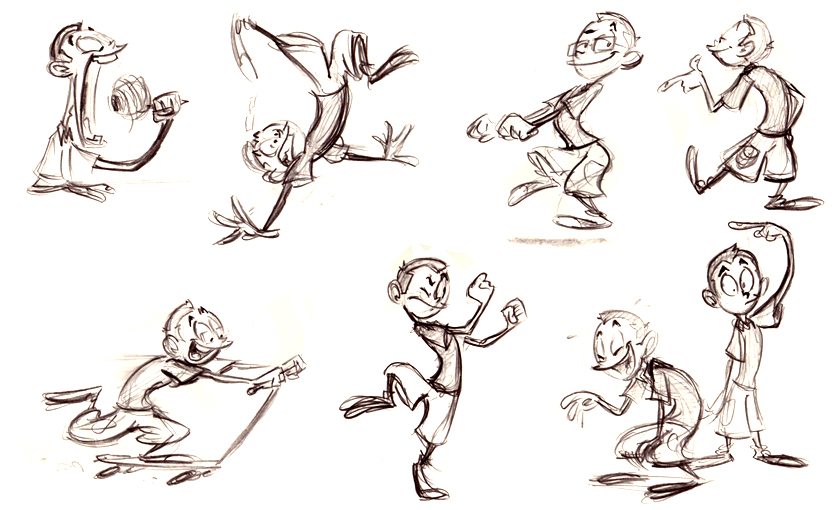

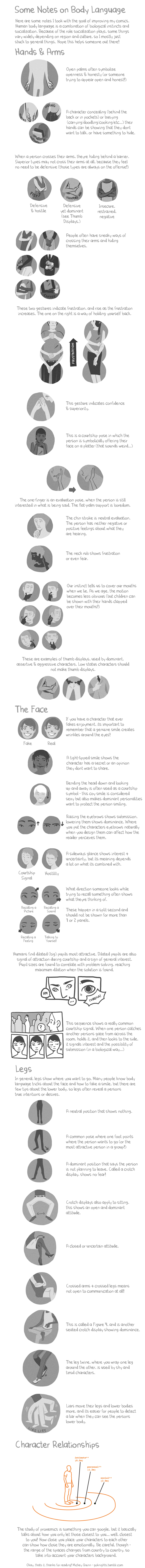

The Power of Postures

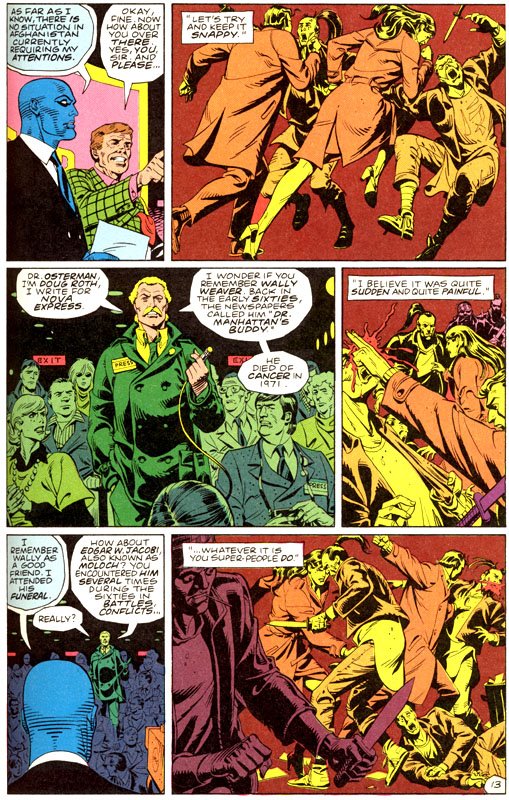

Dave Gibbons (the artist behind "Watchmen") once said: "I don't use action lines to describe what is happening in the frame; I use blood and posture to tell the viewer what is happening".

Posture is a powerful tool for artists, especially here when we're talking about static, sequential art. Posture can tell you all you need to know about what a figure is about to do, what it has just done or what has just happened to it (which obviously is more of a challenge in still drawings than, say, in animation).

The "language of posture" is a universal one - when an artist gets the pose just right, we all know exactly what the figure is doing. So it's clearly hard-wired into our brains. Why, then, is it so hard to learn how to draw figures so that their poses and posture impart their meanings clearly? Perhaps it is the endless combinations of expressions and body postures that make it such a challenging puzzle.

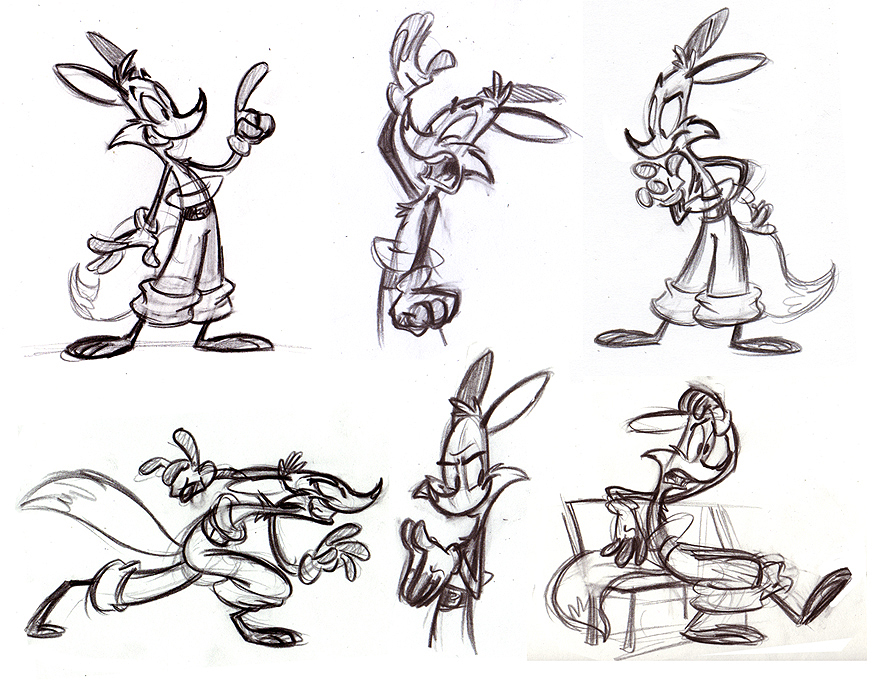

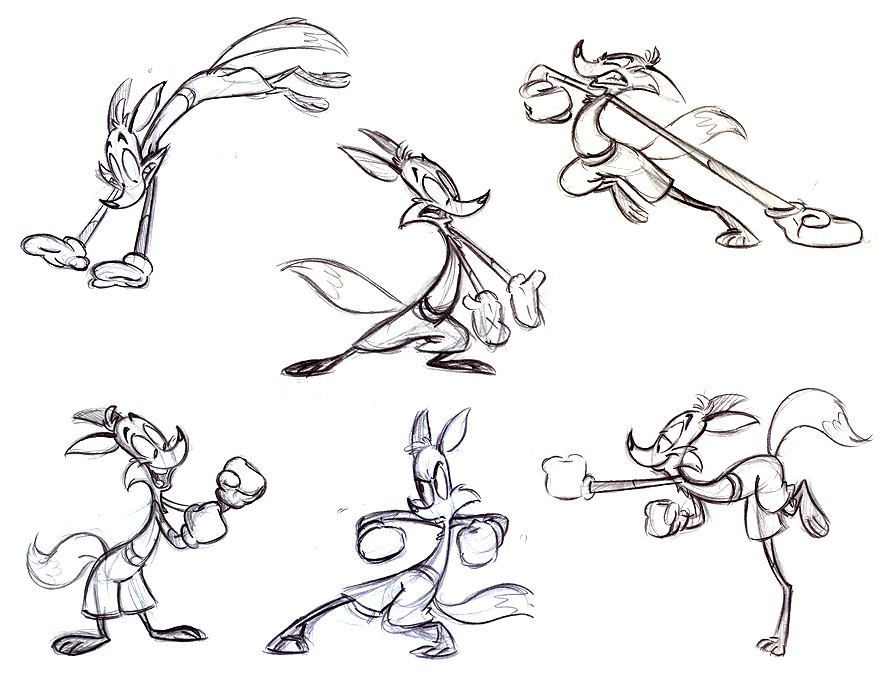

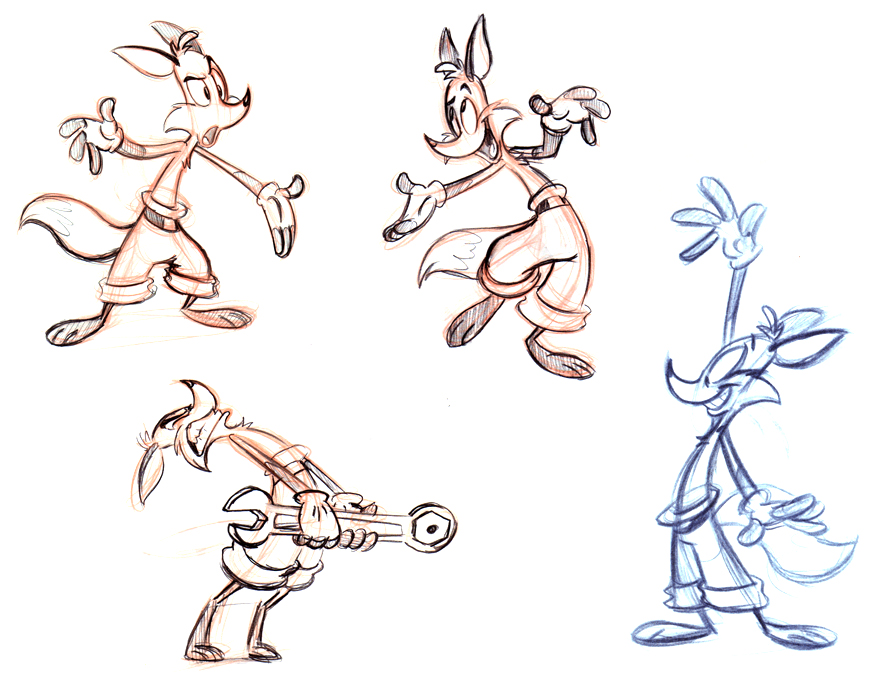

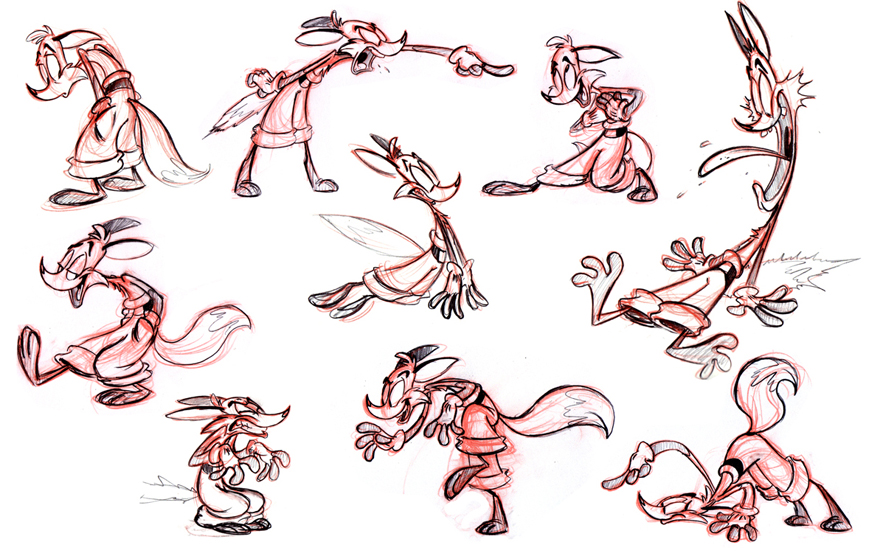

Chuck Jones poses:

These are just tiny examples of how posture can illustrate what is happening within a static drawing and how a character might be feeling... here are some more examples of the excellent use "posture"

"Hellboy" by Mike Mignola

The other part of it (the "blood" part of Dave Gibbons quote), isn't quite as important, any other kind of fluid or solid objects can be used to indicate movement within a static drawing (as well as to help tell the story). Just like posture, it can tell us what just happened, or what is happening right in the moment of the image.

The possibilities are limitless: if a character is smoking, the smoke from their cigarette could show us the path they traveled within the frame. If a character is bleeding, the trail of blood he leaves can show us the path he took. Clothes and hair can also help show us what direction the figure came from and how fast they are moving. These and many other examples can be experimented with to help your posture and other secondary factors to help the action of the shot when storyboarding.

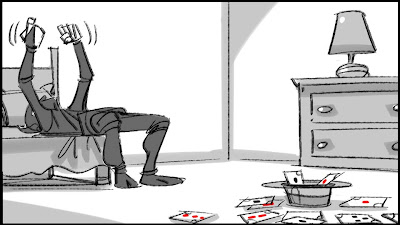

Space & Form

Having a form lay flat against the ground plane (or come into contact with it) can definitely describe the space of your drawing without much else being necessary. A figure laying against the flat ground will tell you a lot about the space by the way the parts of the body overlap one another and move away from the viewer in perspective. Here, the way the body hits the flat ground and the way it squashes against the flat form of the floor gives a solid feeling to the space and feels like there's definitely some depth to the scene. Plus, having the Dad overlap Dennis is helpful to sell what's in front of what (see the last post to read more about overlapping objects to create space).

Similarly to this, you can achieve a nice feeling of space by simply having your character's feet planted firmly in perspective. This can convey a very convincing sense of space when it is done right.

Obviously the same thing applies to anything which is firmly planted on the ground plane and is drawn with perspective that looks convincing. Or even an object that's up in the air.

Just planting different areas in your picture at different heights can be effective. Putting the planes that are further away higher up in the frame is the simplest way to get a sense of space in your drawing.

We all think of having forms shrink as they head off towards the horizon, but don't forget you can give your drawing perspective that recedes in the vertical plane, instead of the horizontal, when appropriate.

The blank areas don't always have to be white; they can be black silhouettes instead, of course. They could even be areas of grey tone as well.

Obviously this is a useful design principle: to balance complex areas against empty areas. It would be meaningless to put one complicated pattern next to another, or to put an empty space next to another. The two types of areas only mean something when balanced by each other for contrast.

Return of the Jedi:

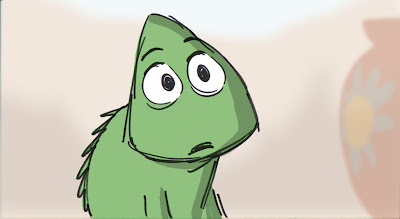

Samples of art by Nicholas Kole, see how the shapes, forms, colors and lighting create appealing compositions.

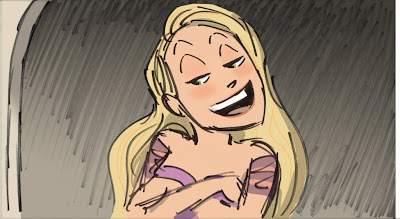

Observe Mark Kennedy's Storyboards for Tangled:

How and When to Cut

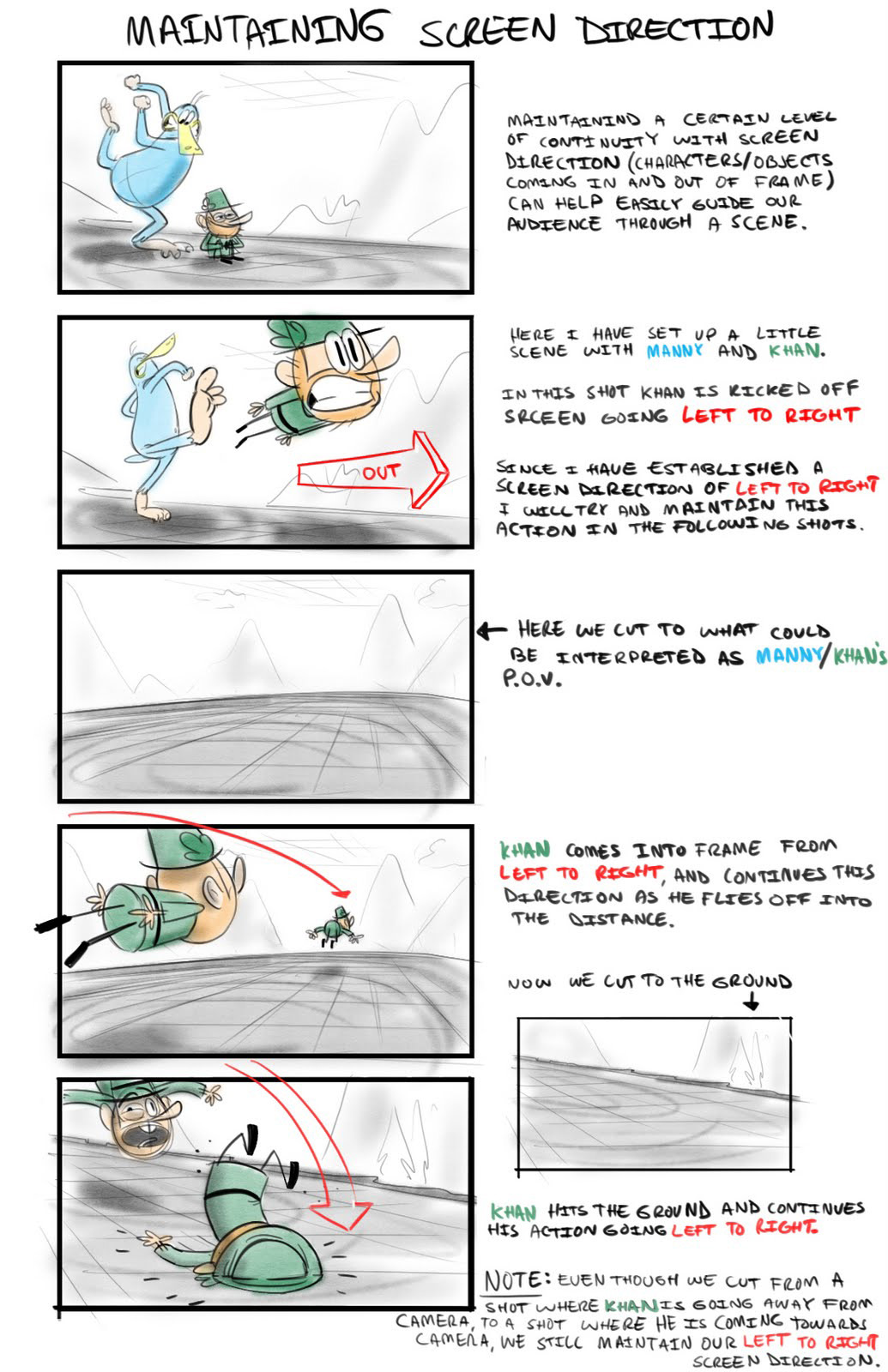

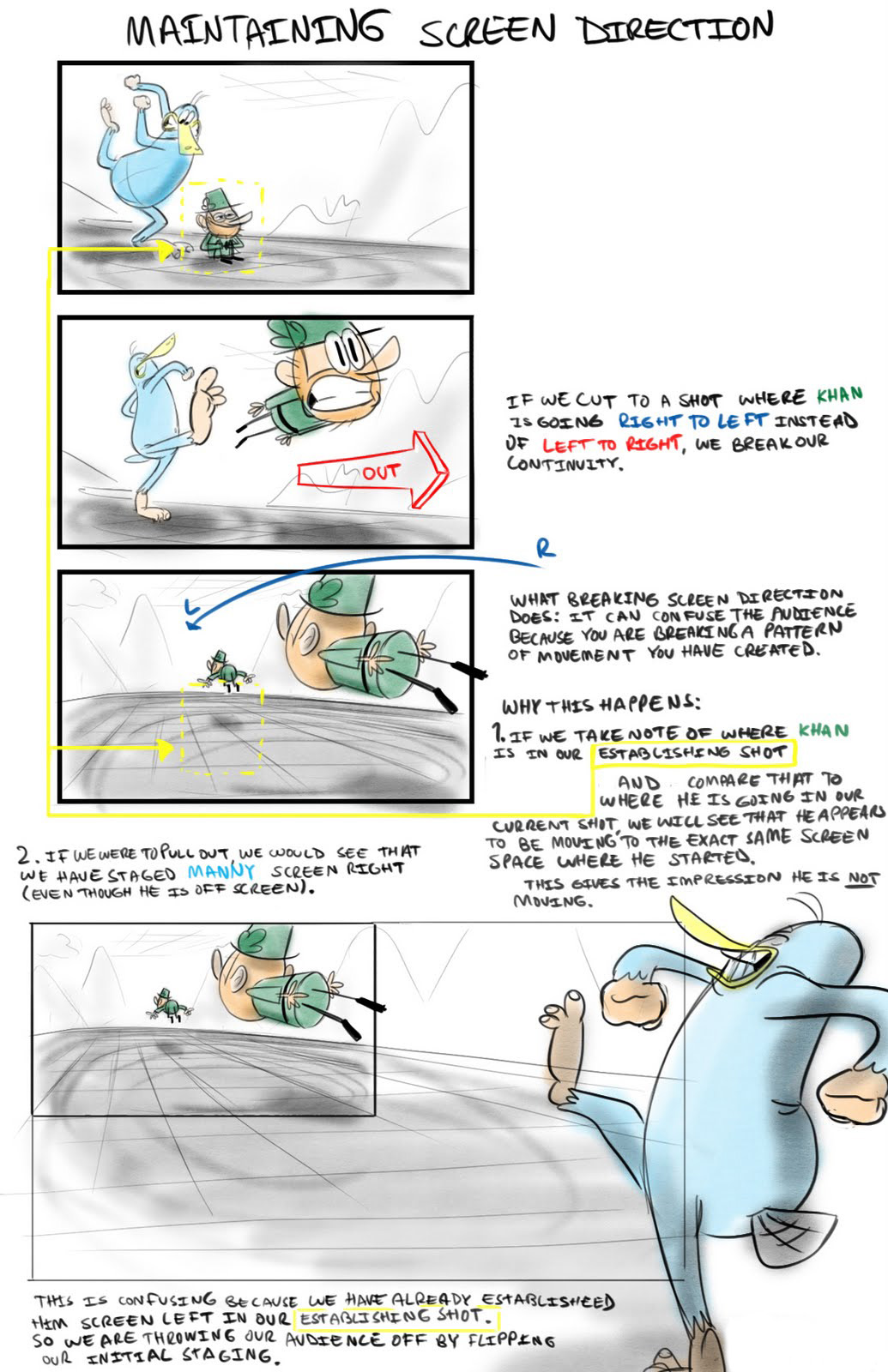

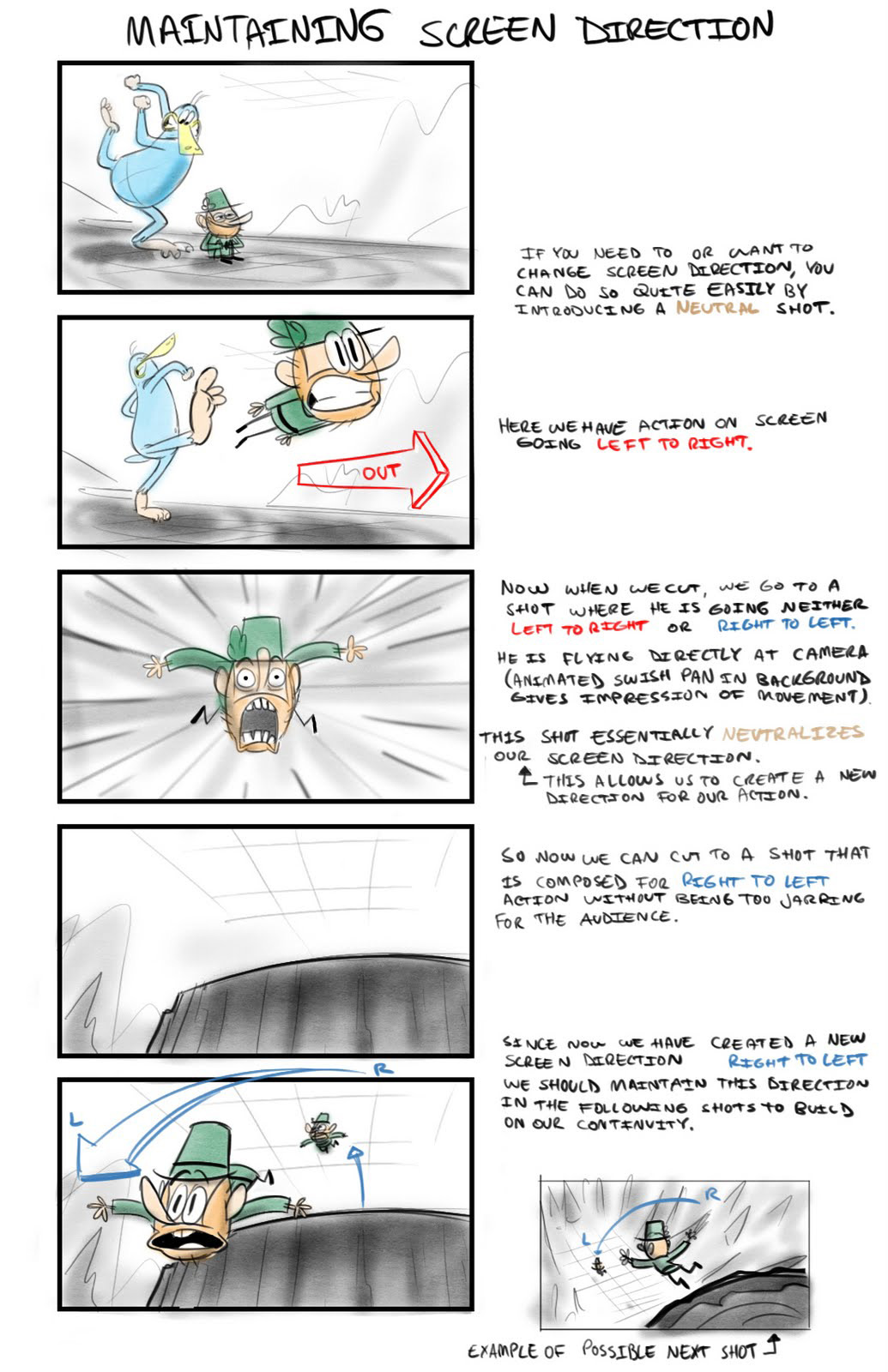

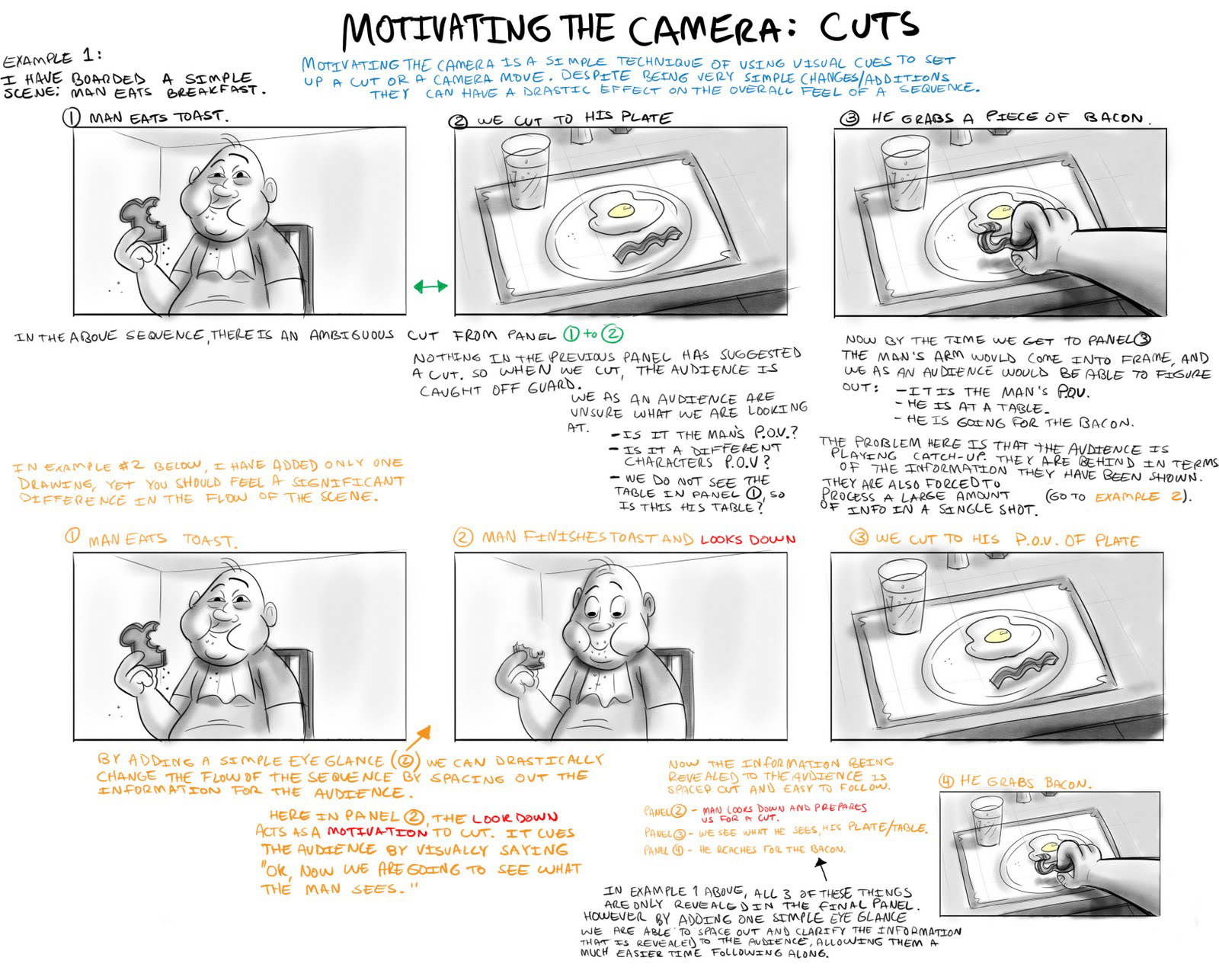

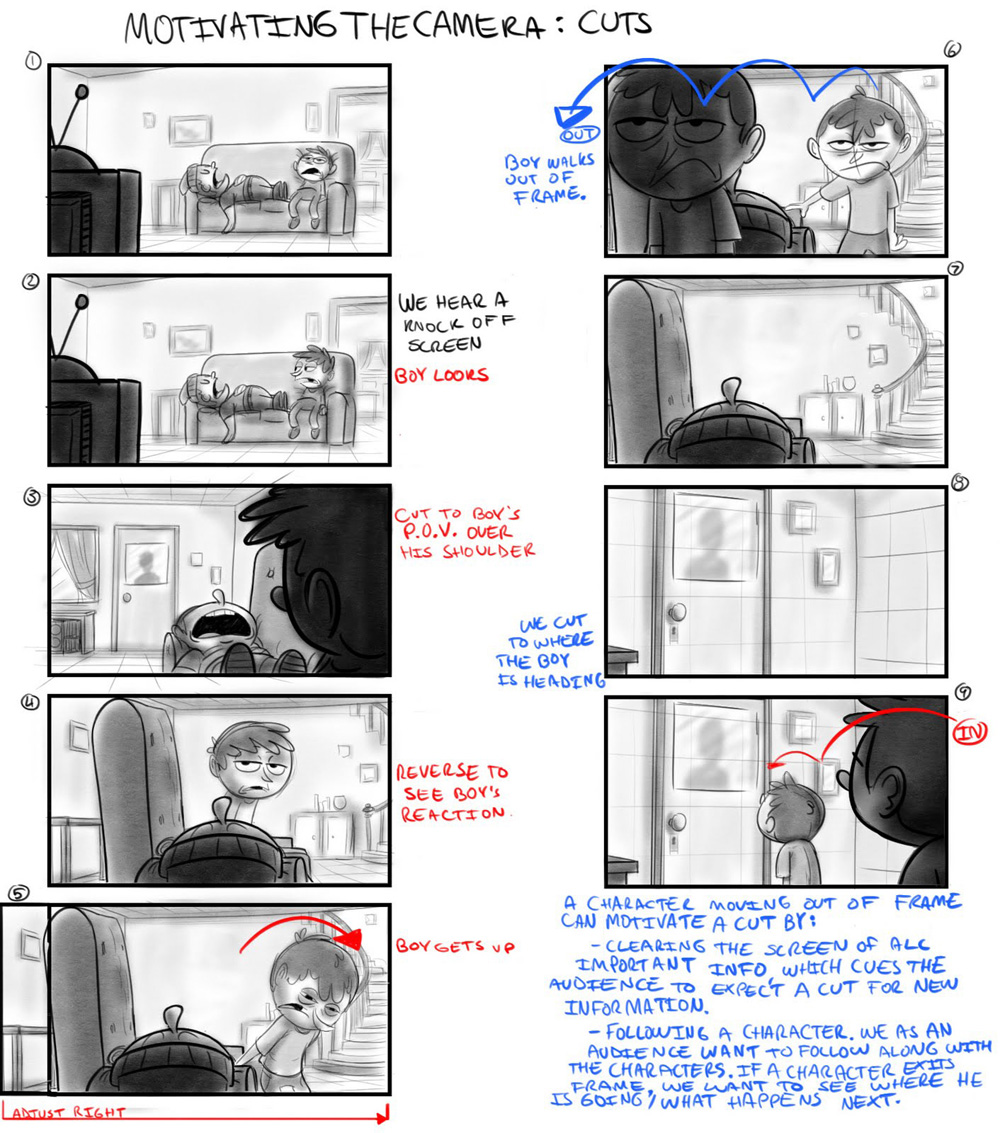

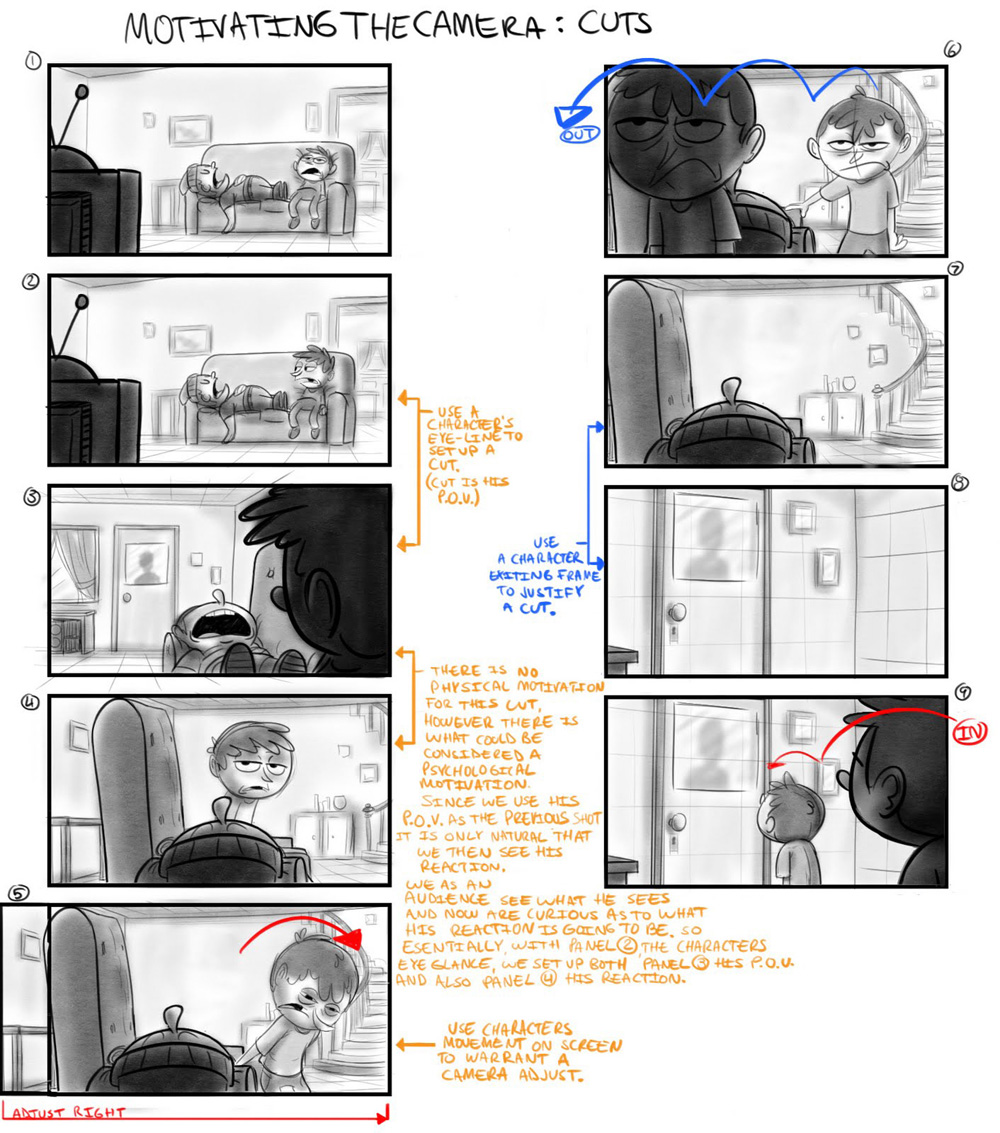

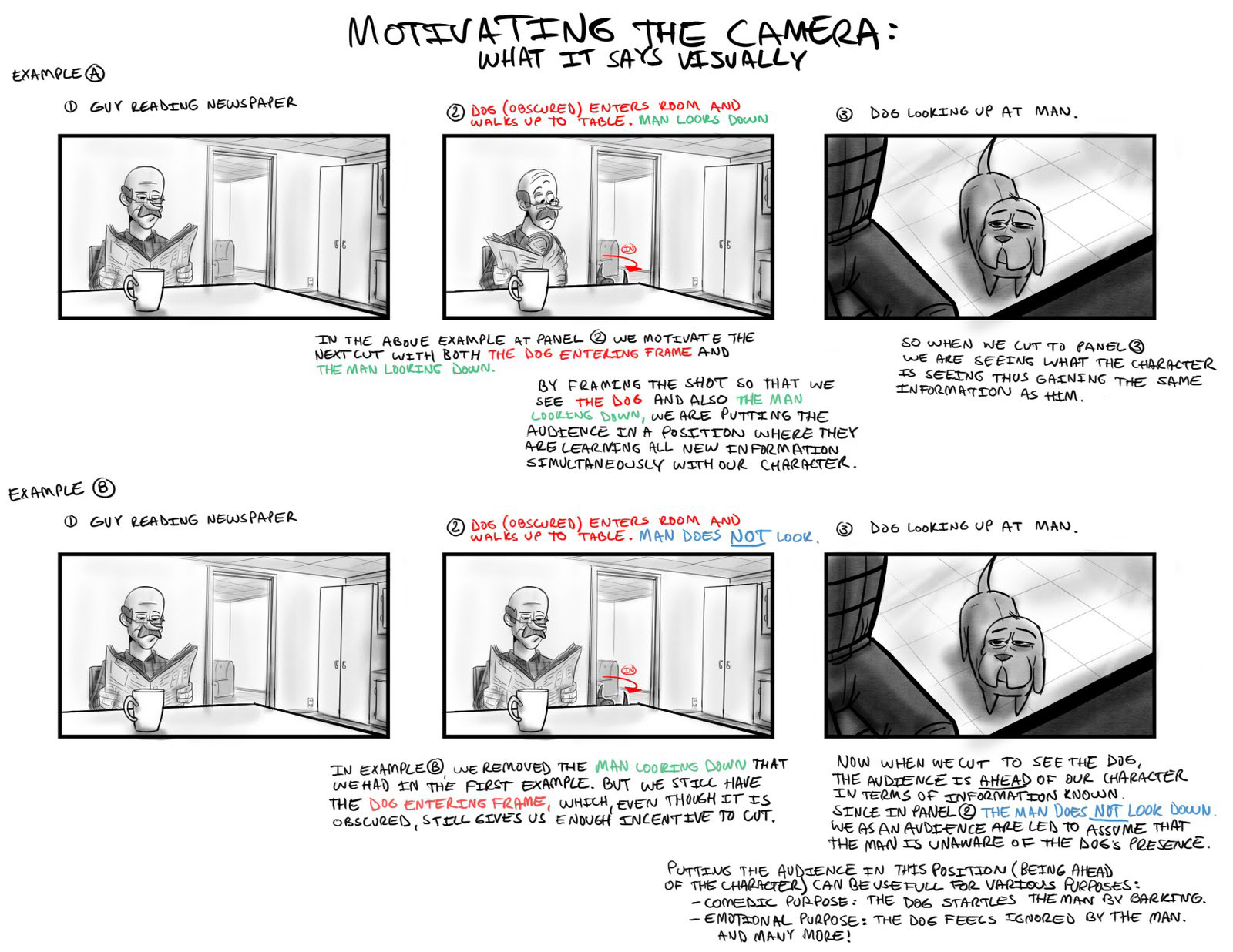

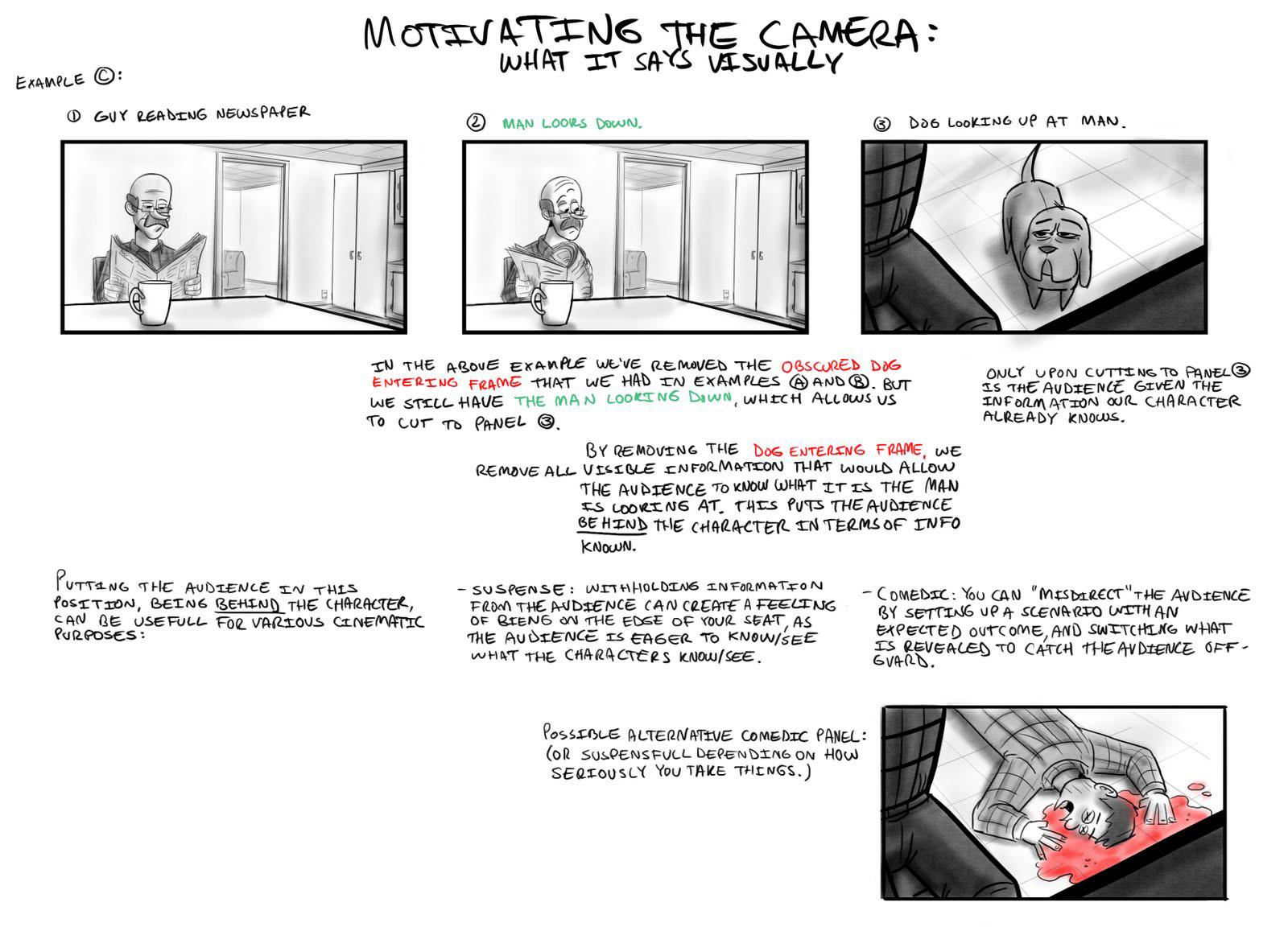

Motivating the camera is a simple technique of using visual cues to set up a cut or camera-move and in doing so, ease the audience into a new shot or new information.

Use a character's eye line to motivate a cut. It helps ease the audience through the cut and into new information. (While also putting us directly in the character's shoes.)

The idea is to create as much continuity within the sequence as possible, making everything clear and easy to follow.

So as per the above sequence, ways to motivate the camera;

- Using a Character's eyeline/P.O.V.

- Having a character move on screen and adjusting the camera accordingly.

- Having a character exit frame.

There are many other ways, for instance;

--- Having a character enter frame.

Ultimately what it comes down to, specifically for 'cutting', is the fact that a 'cut' is not natural, it doesn't happen in real life (unless you take really long blinks). Obviously we have seen enough film/television that we are accustomed to 'cutting', nevertheless, anything you can do to smooth out the transition will only help create and maintain the continuity of your sequence.

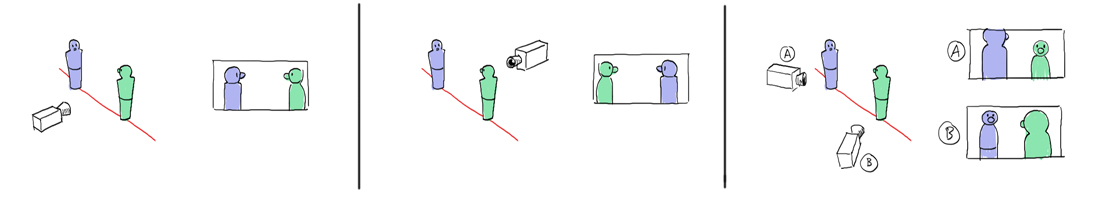

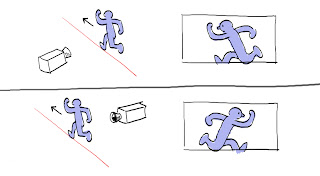

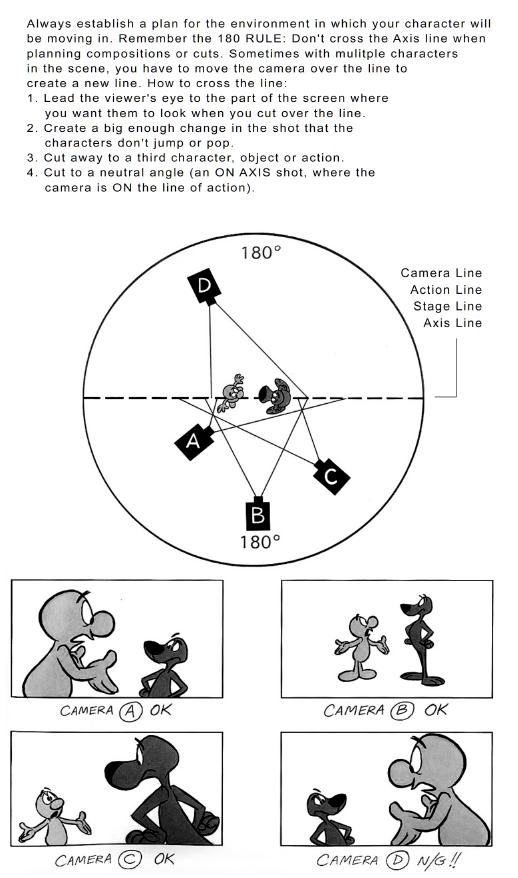

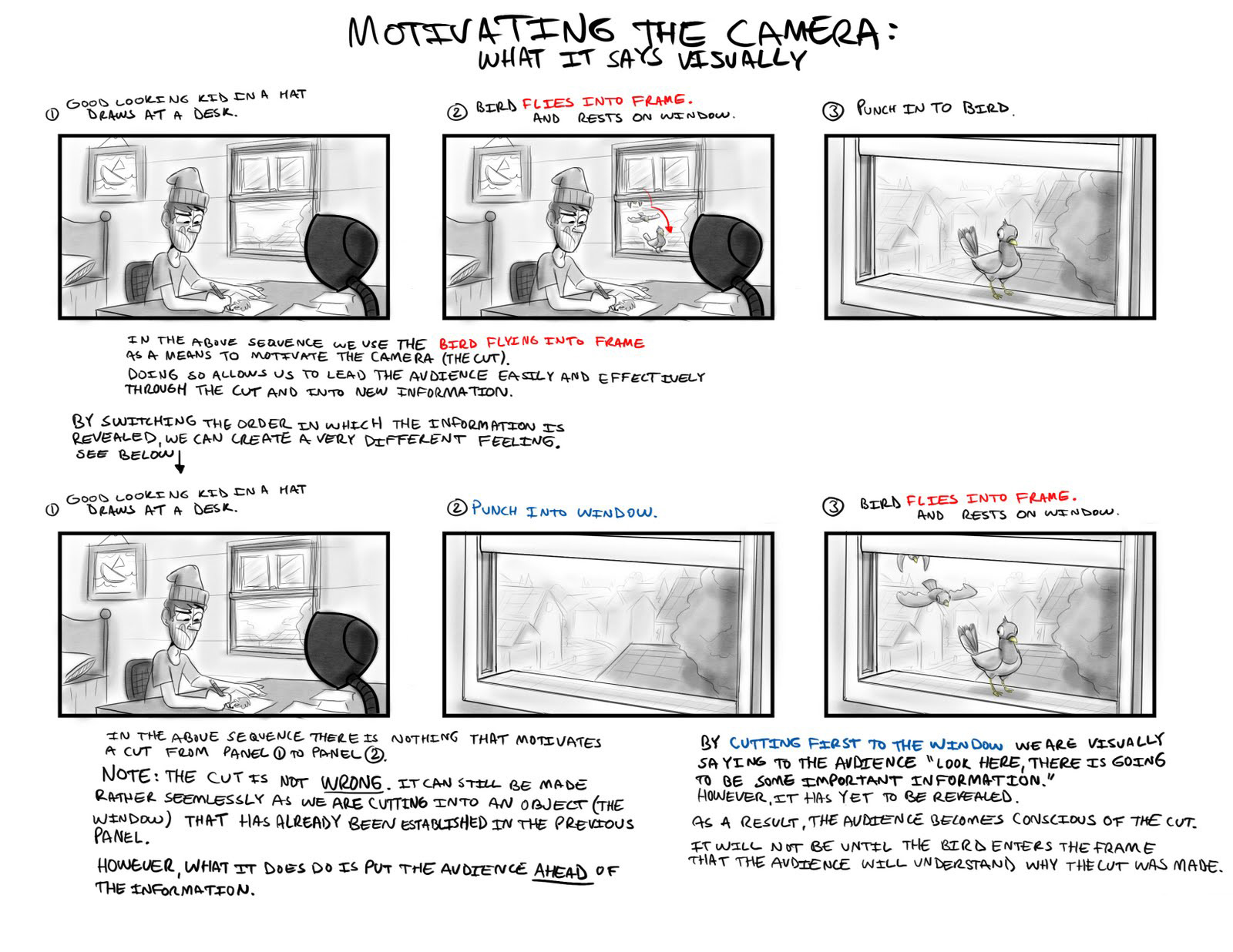

These examples revolve around motivating the camera, and explores more "what they are saying visually".

These examples are all slight variations of the same scene, each exploring a different approach in regards to the progression of information that is revealed to the audience, and consequently the effect it has on them. Ultimately, it all depend on what the script calls for or what is necessary of the scene to determine which of the following (if any) would be suitable.

The most important thing to take away from this concept of 'motivating the camera', is just to try and be conscious of the decisions you are making in your storyboards. Try to understand what you are actually saying visually, what information you are revealing to the audience, when is this information os being revealed, and what effect it will have on them. Thinking about these things as you board can really help enhance a sequence and 'sell' an idea in the storyboard stage.

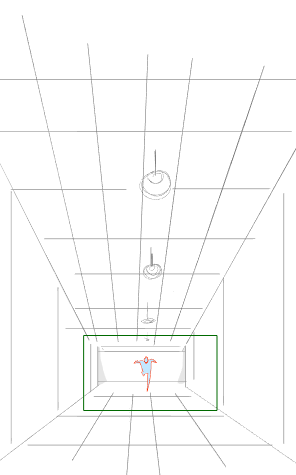

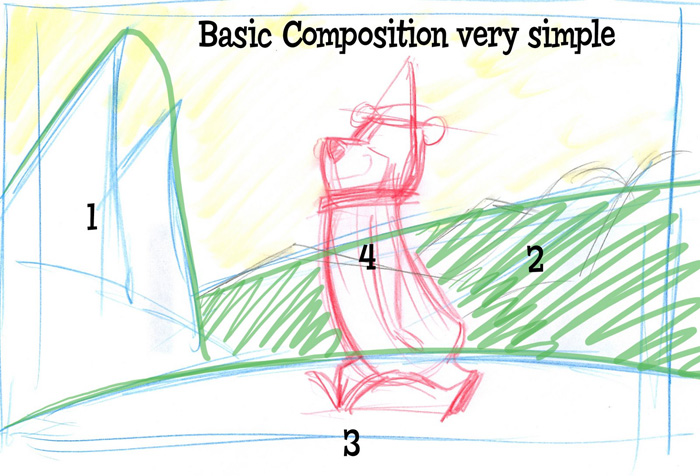

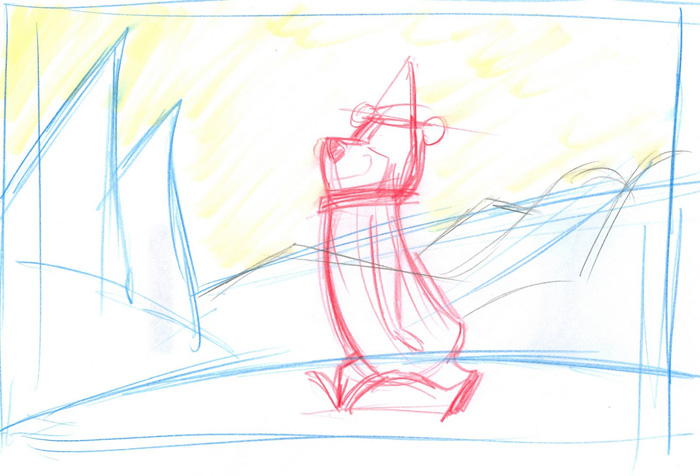

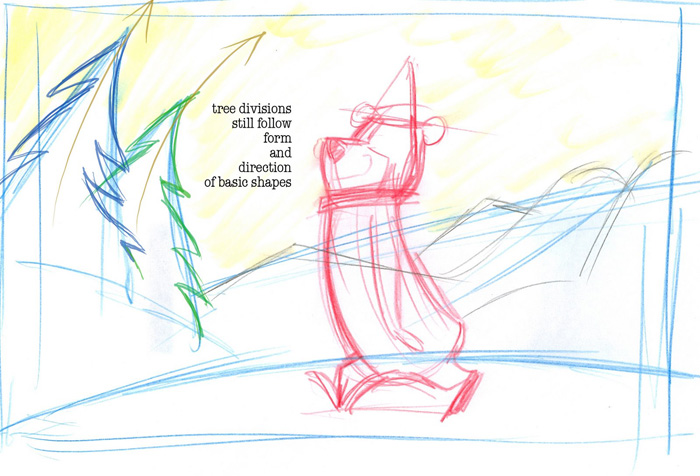

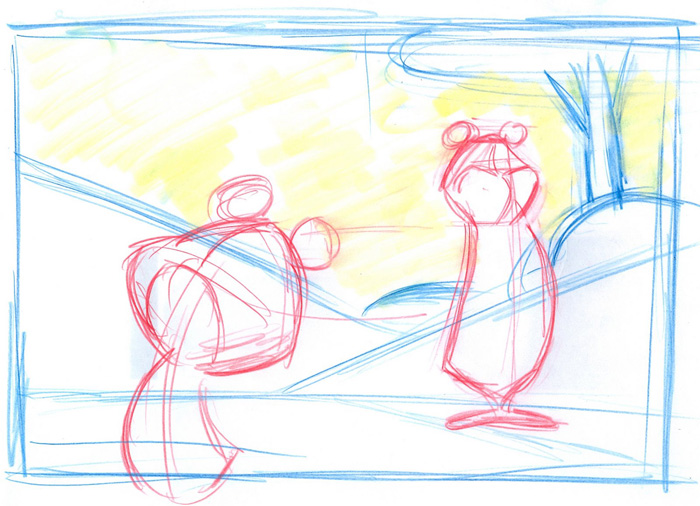

Below is a step-by-step progression of a draw-over from an old storyboard assignment.

1. Original Panel From Student Sequence: Conceptually it is good.

Conceptually it is good.

-She has clearly established a screen relationship between the two characters (left and right).

-Indicated an environment (the mountain range in the background).

My main note is to push it even further! Take the concept of this shot and push it to find a more interesting and compelling composition.

2. Draw Your Grids:

I started my redraw with a horizon line and laying down a grid. Laying down your grids (on the ground, walls and sky) will help clarify the depth of your shot, and can also be used as a guide for incorporating mid/foreground elements (illustrated in step 5).

Laying down your grids (on the ground, walls and sky) will help clarify the depth of your shot, and can also be used as a guide for incorporating mid/foreground elements (illustrated in step 5).

3. Push The Depth:

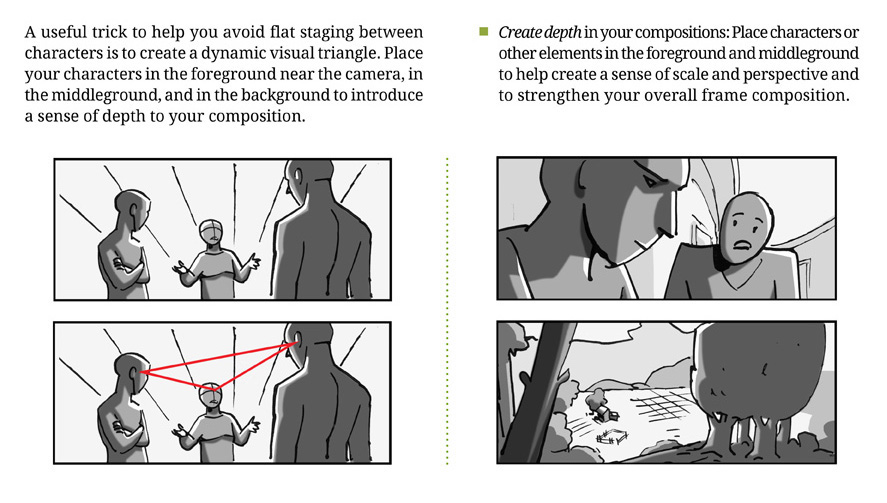

In the original panel there is a lot of empty space around the characters, not particularly interesting or dynamic visually. I drew over the characters, using my grid as a guide, and tried to push the depth. By pushing the depth, bringing one character closer and pushing one further away, you can create a much more engaging composition as well as utilizing the real estate of the panel more effectively.

By pushing the depth, bringing one character closer and pushing one further away, you can create a much more engaging composition as well as utilizing the real estate of the panel more effectively.

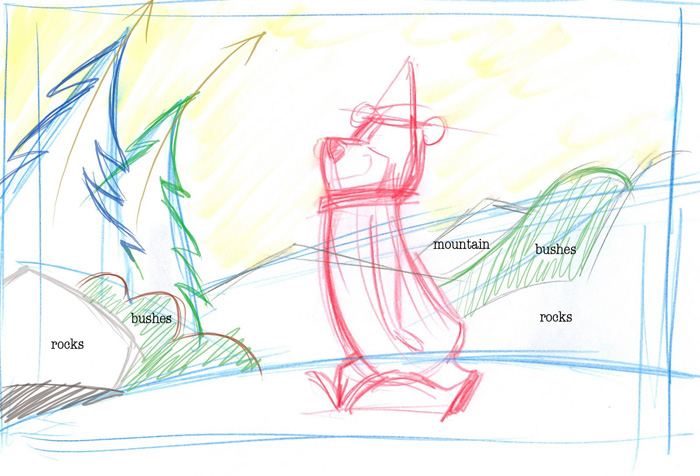

4. Use The Background To Enhance The Composition:

You can use background elements to enhance a composition and help direct the eye. The important information in the panel is the characters, so everything else in the composition should support that. Keeping that in mind, we can use mountain ranges in the distance to help lead the eye to our character.

The important information in the panel is the characters, so everything else in the composition should support that. Keeping that in mind, we can use mountain ranges in the distance to help lead the eye to our character.

5. Populate The Mid-Ground

Put some junk in the mid-ground. Populating the mid-ground can help in a few ways:

Populating the mid-ground can help in a few ways:

-Further help define the environment.

-Help push the depth by incorporating visual depth cues such as over-lapping objects and size relativity (objects get smaller as they recede).

6. A Little Shading Goes A Long Way

In the original panel the shading wasn't particularly adding anything to the composition. A simple way to approach shading is by thinking about it in terms of foreground, mid-ground and background. I did a quick shade pass over the panel using each object's relative position in the composition (how closer/far away it is from us) and shaded accordingly. We can also use shadows to help direct the eye, much like background elements, by having them point towards important information.

I did a quick shade pass over the panel using each object's relative position in the composition (how closer/far away it is from us) and shaded accordingly. We can also use shadows to help direct the eye, much like background elements, by having them point towards important information.

Below is an animated gif of the progression so you can see how being conscious of these principles while you are boarding can really help enhance your work. You may need to click on it to see it animate.

With storyboarding it is just a matter of getting sequences under your belt. The more you board, the better you get, plain and simple. It takes time for these principles to become second nature, don't get discouraged if you don't see them immediately taking effect. The important thing with these concepts is to be aware of them, how they work, and how they can affect your boards. Over time everything will fall into place.